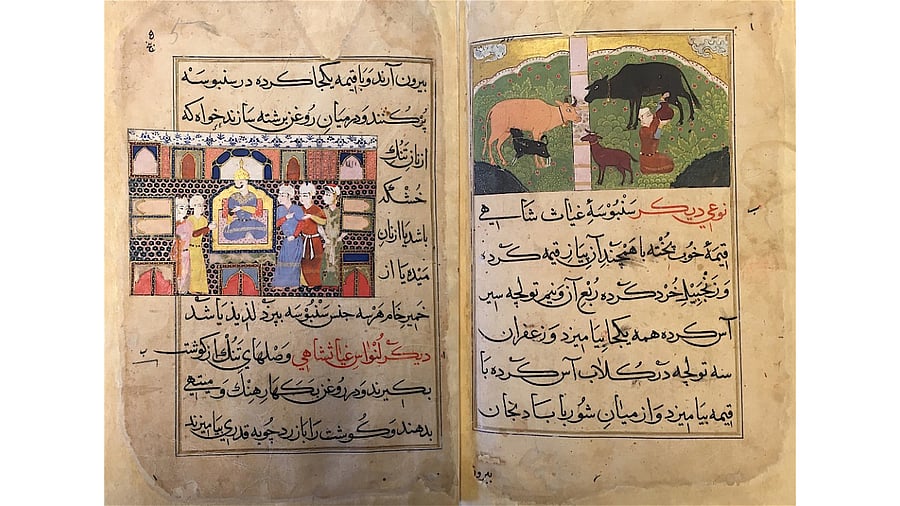

Sultan Ghiyas al-Din seated on his throne. (Right) Illustration showing cows being milked c 1469–1510.

Credit: British Library

In a series of illustrations, a man dressed in royal robes with a distinctive moustache — the Sultan of Malwa (present-day western Madhya Pradesh), Ghiyas al-Din Khilji — consumes paan, oversees the making of samosa, samples kheer, and partakes in culinary delights from his court.

These illustrations appear in a manuscript known as the Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi (Book of Delicacies of Nasir-ud-Din Shah), which the sultan commissioned between 1495 and 1505. The Nimatnama is essentially a book of recipes, and it offers a collection of detailed instructions, formulae and ingredients to prepare a range of sweet and savoury dishes, medicines, salves, perfumes, incense, aphrodisiacs and cosmetics along with a section dedicated entirely to the pleasures of hunting. Believed to have been completed during the reign of Nasir al-Din Shah, the sultan’s son, the manuscript is undated and its artists and authors remain unknown.

As evidenced by the richness of the food it depicts, the sultan intended the making of the book to be a project that would allow him to immerse himself in various sensory pleasures, after having spent many years away from home, thanks to wars and political campaigns. It was a project deeply tied to his own preferences and proof of this appears in the form of comments in the text of the book that proclaim ‘This is delicious’ or ‘This is a favourite of Ghiyath Shahi.’

Written in Persian and Urdu prose using the Naskh script, and containing hundreds of recipes, the book has paintings that illustrate various stages of cooking and eating. The ingredients listed in the recipes often include rare and expensive materials from the Indian subcontinent and beyond — ambergris, saffron, musk, camphor, spikenard, and sandal, indicating that the book was created for royals and people with the means to acquire these materials. Many of the recipes are for dishes that continue to be consumed in India to this day — daal, poori, chapati, khichri, samosas, a variety of elaborate sharbats, shorba, kebabs, lassi, raita, kofta and karhi (or kadhi). Many of these recipes and their ingredients have Persian origins, indicative of the cultural intermingling ushered in by the Sultans, and later, the Mughals. The format of the manuscript and drawing style are also possibly inspired by similar recipe collections from the Persian court. However, as scholars have noted, the style of the drawings becomes increasingly more Indian as one progresses through the book. The book opens with a dedication to an unexpected creature — one that continues to inhabit kitchens and homes even today — “King of cockroaches! Please do not eat this, my offering to the culinary world — recipes of cooking food, sweetmeats, fish and the manufacture of rose-water perfumes.”

We can thank the cockroaches for leaving us with an intact manuscript that allows us to understand how many of the foods we think of as intrinsically Indian were actually influenced by exchanges with Persian and Turkic cultures.

Discover Indian Art is a monthly column that delves into fascinating stories on art from across the sub-continent, curated by the editors of the MAP Academy. Find them on Instagram as @map_academy