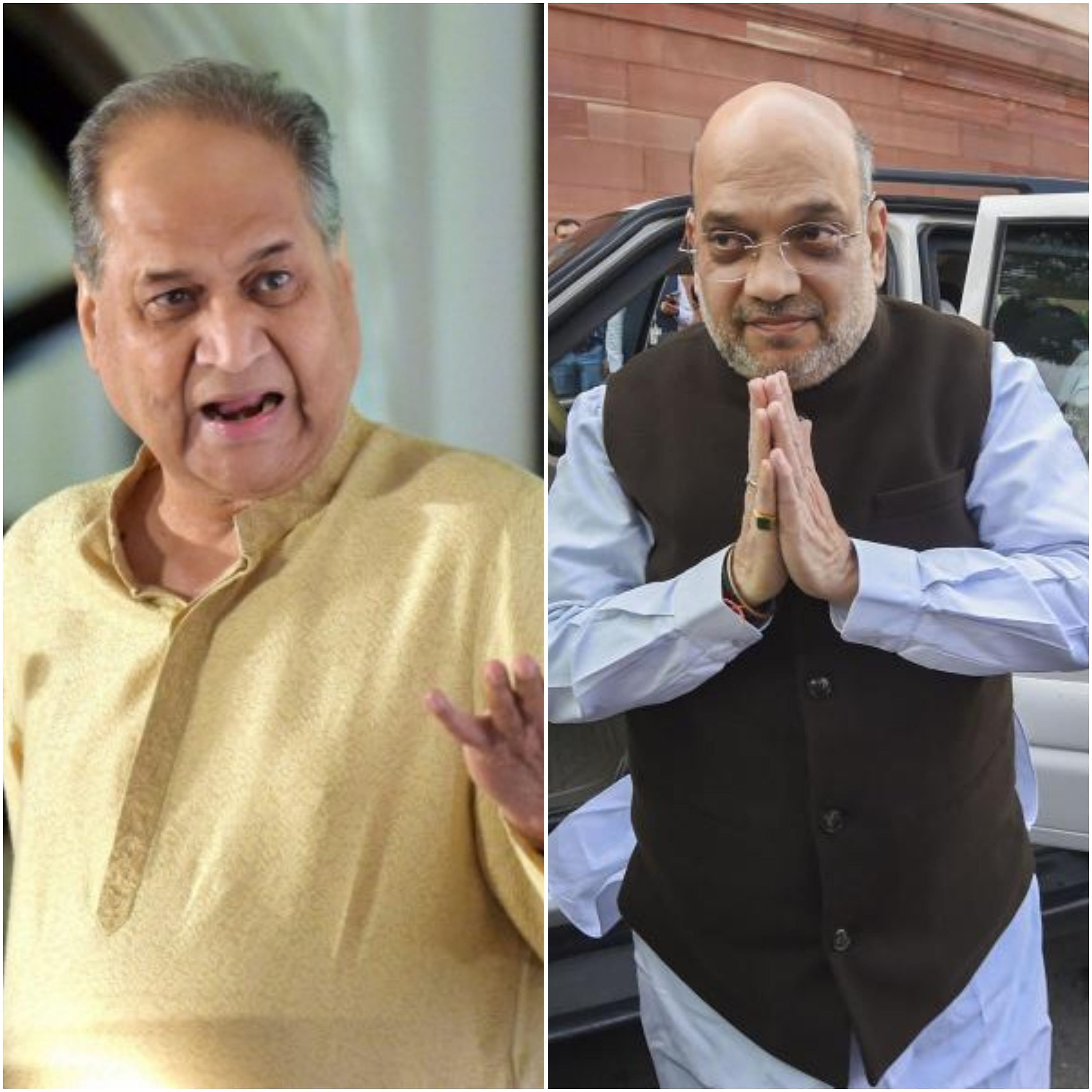

There is much irony in what businessman Rahul Bajaj, who was described as “an outspoken iconoclast”, said about an atmosphere of fear that has stifled the freedom to criticise the government. For, in the past, he thrived on a near-monopolistic position, scuttled competition, and stifled criticism against his scooters. But there is greater irony in the manner in which the government reacted to his comments. Bajaj was dubbed as anti-national, accused of indiscipline, and said to be beholden to the Congress.

The sum of the exchange between the industrialist and the government can be summarised as follows: Bajaj was pointing an accusing finger at the dark economic clouds hovering over India and the government, while claiming to be open to criticism, wanted the damning finger out of sight. Double quick.

It is this attitude of the current policymakers that is significant in this debate. Every time there is an economic crisis, ministers and their loyalists attempt to belittle, dilute, and scoff at those who disapprove of the government’s decisions or the lack of them. This was evident during Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s recent speech in Parliament. Even as she acknowledged that there was a slowdown in the economy, she confidently maintained that there was no recession. The situation was bad, but not worse.

This points to an overall mindset where the imperative is not about finding real solutions or addressing problems but publicly and satirically dismissing accusations. One would assume that a committed government would swing into action to reverse the slowdown, which has worsened over the past few quarters. But no, in Sitharaman’s views, things were not-so-bad, despite factory shutdowns, and lack of jobs. In her scheme of things, government revenues and expenditure had grown and, hence, there was no reason to panic or react with seriousness.

Covering up its tracks

For a ruling regime, the best way to blunt opposition attacks is to blame the latter for the current mess. The finance minister did just this when she said that the slowdown was due to the banking crisis, or the persisting bad loans. And who was responsible for it? The Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA), which was in power for a decade from 2004 to 2014. Remember, Sitharaman is absolutely right about the slowdown and the origins of the banking mess. But a focus on such issues does not lead to solutions. It only results in useless rhetoric.

Having observed the behaviour of several governments in the past, one can safely conclude that there may be nothing uncharacteristically devious about this, or that the present regime is completely conscious about what it is doing. The fact is that there is a subconscious realisation among the current crop of policy-makers, as was the case with its predecessors, that there are no quick-fix solutions to economic crises. Only a long-term vision (Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew) or a radical surgery – US Federal Reserve’s pumping in of trillions of dollars to sort out the 2008 Global Financial Crisis – can kick-start or reverse an economy.

This government was unable to do either. In the first two years, the National Democratic Alliance-II did come up with grandiose schemes such as Make in India, Digital India, and Skill India. But it soon understood that mere ideas don’t yield results. In fact, by 2016, disruptive policies in all spheres became its mainstay. In the economic realm, demonetisation, Goods and Services Tax, and the insolvency code fall into this category. Disruptions, by their very nature, are aimed to do away with stability, something that scares every investor.

One of the unintended consequences of disruptive economics, especially if it is driven from the top, is that it makes those down the line believe that changes are game-changers and revolutionary. They publicly declare that they are aimed to re-build a new India over the rubble and ruins of the past. Another one is that the decision-makers are left with mere tinkering and tweaking of policies to make a show of their intentions to deal with the ensuing crises. Unfortunately, such an approach invariably fails to deliver.

Decoupling electoral politics from economics

The intended consequence is that disruptions force common people to shuffle around like a headless chicken, as they reel from one crisis to another. The efforts to deal with immediate situations make them miss the larger picture. In many ways, they become immune to abstract ideas like a slowdown in growth, lack of jobs, or lack of investments. Instead, they stand in queues to return large denomination notes and withdraw cash, change their financial books to shift to the GST regime, and wonder how the lenders can declare their centuries-and-decades-old-businesses as insolvent if they fail to repay their loans, irrespective of whether they are wilful defaulters or honest entrepreneurs.

In essence, electoral politics is thereby decoupled or delinked from economics. This is initially deliberate as people are told, either rightly or wrongly, that their sufferings are minimal compared to the powerful elites, who are corrupt and criminal. Thus, demonetisation crippled the evil rich, and only caused minor worries for the honest poor. GST forced the tax evaders to pay. Insolvency code allowed the state-owned banks to snatch away the businesses of dishonest and politically-linked businessmen.

Over time, the decoupling between politics and economics becomes a self-serving exercise. As long as voters and citizens are busy with their daily duels, elections are won by different and varying narratives. When this happens, everything is seen from the lens of politics. Even routine economic decisions are taken with political objectives in mind. The urge to fix the economy, if it is in trouble, vanishes subconsciously.

(Alam Srinivas is an independent investigative journalist)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.