The North Pole is melting faster than ever, but the chill in the air at this year’s global gathering of Arctic experts had more to do with the widening repercussions of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The planetary consequences of that war have, by now, reached far beyond the disruption of climate efforts in Europe, where gas shortages have prompted governments to recommission coal plants. The conflict has also intensified a race among great powers for ascendancy in the Arctic, adding to pressure on a fragile system that’s critical to mitigating global warming.

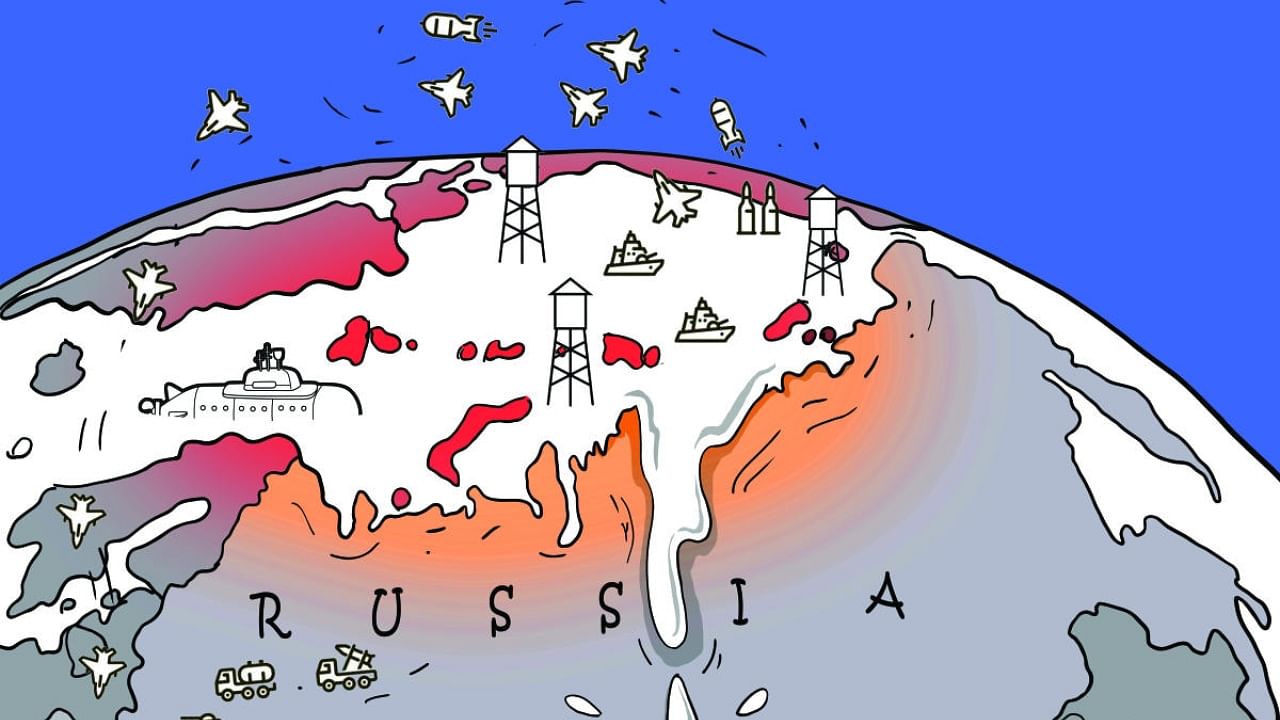

Not since the Cold War has there been such focus on the frigid expanse that caps the Earth. More than half the Arctic coastline belongs to Russia, which is increasingly isolated from its northern neighbours. That’s turned the region into a growing security concern for the US, which has a foothold through Alaska.

As a result, this year’s Arctic Circle Assembly at times took on the air of a geopolitical summit rather than a gathering of climate and development experts. While Russia was noticeably absent from the event held last week in Reykjavik’s iconic glass-scaled Harpa Concert Hall, an unprecedented 2,000 attendees spilled into corridors and wedged themselves into doorways. Military uniforms popped out among the dark suits of politicians, executives and scientists. And the conference drew a record number of US officials armed with the first update to America’s Arctic strategy in a decade.

War in Europe has already derailed other efforts at regional cooperation. Meetings of the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum promoting cooperation on biodiversity, climate and pollution, have been suspended since the war began in February.

While climate remains a pillar of US policy, Derek Chollet, Counsellor at the US State Department, told me — security takes precedence. Of greatest concern to the US would be any move by Russia to restrict freedom of navigation, build military forces or test certain high-tech weapons in the Arctic, but it is also worried about China’s growing interest in the region.

“As we’ve seen elsewhere where China has chosen to be a regional player, that’s often in a zero-sum way,” Chollet said. “I don’t think it’s in any of our interests to see the Arctic become another example of this.”

Russia set up a Northern Command in 2014, opening multiple new and former Soviet military sites in the Arctic. It’s also developing new nuclear submarines for Arctic operations, including Arcturus, which can deploy underwater drones and hypersonic missiles. The shortest route to North America from Russia is still over the top of our planet and the new missiles will require near-instantaneous reaction time, military experts say.

The US is working with Arctic ally Canada to revitalise a Cold War era joint aerospace defence command. And once Sweden and Finland’s accession to NATO is complete, Russia will be the only Arctic state outside that key defence alliance, also forged during the Cold War as a bulwark against Soviet expansion in Europe. All that adds to an overwhelming sense that the world is returning to an era of great powers competing for resources and security, rather than collaborating over climate.

If geopolitics is side-lining efforts to slow the melt, climate change is simultaneously undermining what, until recently, was the Arctic’s best defence: its inaccessibility. The region’s ice reflects the sun’s heat and its permafrost acts as a huge carbon vault, helping to cool the planet — but how do you protect an Arctic that’s being cracked open as it thaws?

The North Pole’s lost about 40 per cent of its ice since the 1980s and is now warming roughly four times as fast as the rest of the world. That’s opening it up to marine traffic and economic development which, in turn, is expected to amplify the effects of global warming.

Temperatures over the central Arctic Ocean this summer were 1 to 4 degrees Celsius higher than the 20 year average up to 2020, according to the Colorado-based National Snow & Ice Data Centre. Mark Serreze, the organisation’s director, said it was the first time he can remember that both the major routes through Canada’s Northwest Passage and Russia’s Northern Sea Route were “essentially ice free” all summer.

For years, Russia has benefitted from the Northern Sea Route, a key section of the Northeast Passage that connects the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans across the Arctic. Stretching through Russia’s Exclusive Economic Zone, the route is frequently ice-free in summer and Russian ice-breakers can make it accessible in winter to friendly nations. A voyage from Japan to Europe can take just 10 days through this Arctic Circle route – compared to more than 20 via the Suez Canal and more than 30 to sail around the Cape of Good Hope.

The route’s competitor, the fabled Northwest Passage, took Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen three years to navigate at the turn of the 20th century. That was long before it became ice-free for the first time in the summer of 2007, but it still remains trickier to traverse. With US-led sanctions against Russia triggering a collapse in international transit along the Northern Sea Route this year, however, the Northwest Passage could become more attractive to shipping, especially as temperatures rise.

The third option is, so far, hypothetical. Should the North Pole ever melt entirely — and all indications are that it will, probably before mid-century — the Trans Arctic shipping route would allow ships to travel straight over the top, through international waters, avoiding sticky interactions along anybody’s coast. A decade or more before that, it could become ice-free in summer. But there would be severe trade-offs in a world with a watery Arctic. The disappearance of the Greenland ice sheet, the world’s second-largest body of ice, would cause sea levels to rise 6 meters (20 feet), threatening islands and coastlines thousands of miles away. Swathes of the Middle East, Africa and Asia would become too hot to live in. And whatever financial gains are made could be erased by more extreme storms, floods, fires and droughts around the world.

So far, that dire prospect is not putting anyone off. China, which has no Arctic coastline, is betting on the end of ice. Its Belt and Road Initiative includes plans for a Polar Silk Road connecting East Asia, Western Europe and North America. The emergence of a trans-Arctic shipping route is key to that strategy and would create an alternative to its maritime route through the South China Sea, Strait of Malacca and Suez Canal. It’s working on the world’s biggest ice-breaker to support that ambition.

Opening up the Arctic would also ease access to planet-warming fossil fuels. About 90 billion barrels of oil and 1,670 trillion cubic feet of gas lie inside the Arctic Circle, according to the United States Geological Survey, along with metals and minerals needed for electrification.

Under the Law of the Sea, most Arctic nations have claims to some of its resources, but whether to restrict planet-harming development is up to individual governments. Greenland last year banned new licenses for oil and gas drilling and Iceland plans to prohibit exploration, while oil majors, wary of the reputational damage associated with drilling pristine wilderness, have signalled they’ll stay away. Scandinavian nations are hoping to harness the region’s wind and hydro power. In contrast, Russia — already by far the largest Arctic energy producer — is looking to expand oil and gas production.

“Geopolitics in the Arctic is changing,” Alar Karis, president of Estonia, which has applied for observer status on the since shuttered Arctic Council, told the conference. “Therefore we must not only think of climate and the environment, but also diplomacy and deterrence.”