Few Americans have heard of Sharp. But for decades, his practical writings on nonviolent revolution — most notably ‘From Dictatorship to Democracy,’ a 93-page guide to toppling autocrats, available for download in 24 languages — have inspired dissidents around the world, including in Myanmar, Bosnia, Estonia and Zimbabwe, and now Tunisia and Egypt.

When Egypt’s April 6 Youth Movement was struggling to recover from a failed effort in 2005, its leaders tossed around ‘crazy ideas’ about bringing down the government, said Ahmed Maher, a leading strategist. They stumbled on Sharp while examining the Serbian movement Otpor, which he had influenced.

When the nonpartisan International Centre on Nonviolent Conflict, which trains democracy activists, slipped into Cairo several years ago to conduct a workshop, among the papers it distributed was Sharp’s ‘198 Methods of Nonviolent Action’, a list of tactics that includes hunger strikes, ‘protest disrobing’ and ‘disclosing identities of secret agents’.

Dalia Ziada, an Egyptian blogger and activist who attended the workshop and later organised similar sessions on her own, said trainees were active in both the Tunisia and Egypt revolts. She said that some activists translated excerpts of Sharp’s work into Arabic and that his message of “attacking weaknesses of dictators” stuck with them.

Peter Ackerman, a one-time student of Sharp’s who founded the nonviolence centre and ran the Cairo workshop, cites his former mentor as proof that ‘ideas have power.’

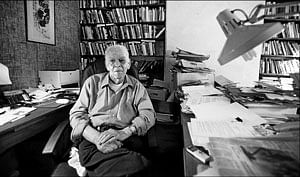

Sharp, hard-nosed yet exceedingly shy, is careful not to take credit. He is more thinker than revolutionary, though as a young man he participated in lunch-counter sit-ins and spent nine months in a federal prison in Danbury as a conscientious objector during the Korean War. He has had no contact with the Egyptian protesters, he said, although he recently learned that the Muslim Brotherhood had ‘From Dictatorship to Democracy’ posted on its website.

While seeing the revolution that ousted Hosni Mubarak as a sign of ‘encouragement,’ Sharp said: “The people of Egypt did that — not me.”

He has been watching events in Cairo unfold on CNN from his modest house in East Boston, which he bought in 1968 for $150 plus back taxes.

It doubles as the headquarters of the Albert Einstein Institution, an organisation Sharp founded in 1983 while running seminars at Harvard and teaching political science at what is now the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth. It consists of him; his assistant, Jamila Raquib, whose family fled Soviet oppression in Afghanistan when she was 5; a part-time office manager and a Golden Retriever mix named Sally.

Some people suspect Sharp of being a closet peacenik and a lefty — in the 1950s, he wrote for a publication called ‘Peace News,’ and he once worked as personal secretary to A J Muste, a noted labour union activist and pacifist — but he insists that he outgrew his own early pacifism and describes himself as ‘trans-partisan.’

Why peaceful protest

Based on studies of revolutionaries like Gandhi, nonviolent uprisings, civil rights struggles, economic boycotts and the like, he has concluded that advancing freedom takes careful strategy and meticulous planning, advice that Dalia said resonated among youth leaders in Egypt. Peaceful protest is best, he says — not for any moral reason, but because violence provokes autocrats to crack down.

“If you fight with violence,” Sharp said, “you are fighting with your enemy’s best weapon, and you may be a brave but dead hero.”

Autocrats abhor Sharp. In 2007, president Hugo Chavez of Venezuela denounced him, and officials in Myanmar, according to diplomatic cables obtained by the anti-secrecy group WikiLeaks, accused him of being part of a conspiracy to set off demonstrations intended ‘to bring down the government.’ (A year earlier, a cable from the US embassy in Damascus noted that Syrian dissidents had trained in nonviolence by reading Sharp’s writings.)

“He is generally considered the father of the whole field of the study of strategic nonviolent action,” said Stephen Zunes, an expert in that field at the University of San Francisco. “Some of these exaggerated stories of him going around the world and starting revolutions and leading mobs, what a joke. He’s much more into doing the research and the theoretical work than he is in disseminating it.”

That is not to say Sharp has not seen any action. In 1989, he flew to China to witness the uprising in Tiananmen Square. In the early 1990s, he sneaked into a rebel camp in Myanmar at the invitation of Robert L Helvey, a retired army colonel who advised the opposition there. They met when Helvey was on a fellowship at Harvard; the military man thought the professor had ideas that could avoid war.

“Here we were in this jungle, reading Gene Sharp’s work by candlelight,” Helvey recalled. “This guy has tremendous insight into society and the dynamics of social power.”

Not everyone is so impressed. As’ad AbuKhalil, a Lebanese political scientist and founder of the Angry Arab News Service blog, was outraged by a passing mention of Sharp. He complained that western journalists were looking for a ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ to explain Egyptians’ success, in a colonialist attempt to deny credit to Egyptians.

Still, just as Sharp’s profile seems to be expanding, his institute is contracting. Ackerman, who became wealthy as an investment banker after studying under Sharp, contributed millions of dollars and kept it afloat for years. But about a decade ago, Ackerman wanted to disseminate Sharp’s ideas more aggressively, as well as his own. He put his money into his own centre, which also produces movies and even a video game to train dissidents. An annuity he purchased still helps pay Sharp’s salary.

In the twilight of his career, Sharp, who never married, is slowing down. His voice trembles and his blue eyes grow watery when he is tired; he gave up driving after a recent accident. He does his own grocery shopping; his assistant, Jamila, tries to follow him when it is icy. He does not like it.

Sharp says his work is far from done. He has just submitted a manuscript for a new book, ‘Sharp’s Dictionary of Power and Struggle: Terminology of Civil Resistance in Conflicts’, to be published this fall by Oxford University Press. He would like readers to know he did not pick the title.

“It’s a little immodest,” he said.

He has another manuscript in the works about Einstein, whose own concerns about totalitarianism prompted Sharp to adopt the scientist’s name for his institution. (Einstein wrote the foreword to Sharp’s first book, about Gandhi.)

In the meantime, he is keeping a close eye on West Asia. He was struck by the Egyptian protesters’ discipline in remaining peaceful, and especially by their lack of fear.

“That is straight out of Gandhi,” Sharp said. “If people are not afraid of the dictatorship, that dictatorship is in big trouble.”

The New York Times