Padmanath Gohain Baruah was among the founders of both the Kohima Sahitya Sabha (KSS), the oldest institution of its kind in the Naga Hills, and its better-known younger cousin the Asam Sahitya Sabha. His plays included Joymoti, based on the life of an Assamese princess whose husband took shelter in the Naga Hills. Joymoti’s character has also inspired other landmark contributions to Assamese literature and cinema, including the first Assamese movie.

While the KSS continued to attract people after Nagaland’s separation from Assam, its appeal has declined over the years. Today the KSS building, which stands neglected right in the heart of Kohima, reflects the sorry state of the Naga-Assamese relationship.

Cultural and political ties have not been completely severed though. Nisheli, the first Nagamese play, was directed by an Assa-mese (Nagamese, an Assamese-based pidgin, is Nagaland’s lingua franca). The auth-ors of one of the first Nagamese dictionaries and grammars were also Assamese.

Students’ organisations and political leaders of the two states still enjoy a close relationship. Former Assam chief minister Prafulla Mahanta and the then Nagaland chief minister Neiphiu Rio played an important role in launching the North-East Regional Parties’ Front before the 2014 elections.

Yet, things have changed. The boundary dispute that has claimed hundreds of lives over the past four decades exemplifies the change. While the state governments passed the buck to the Supreme Court, the Union government subcontracted its job to various commissions. However, the dispute can be resolved only through a sustained dialogue that is sensitive to history and involves local stakeholders.

The Brahmaputra Valley’s Ahom rulers allowed the Nagas to visit markets near the foot hills that served as hubs for exchange between the hills and the plains (Nagamese has its origins in, among other things, these markets). When this arrangement broke down, the Nagas raided the plains for goods and the Ahoms responded in kind. Eventually, peaceful exchange resumed after a new compact was negotiated and occasionally buttressed by marriage alliances.

The Ahoms had marriage ties with Konyak Nagas of Mon. Perhaps even the far off Angami Nagas of Kohima entered into marriage relations with the Ahoms, when the latter attacked the Dimasa-Kachari kingdom. While most Dimasas fled Dimapur, some married and settled in the Angami territory in the hills. Ironically, two centuries later, the Ahoms too took shelter in the Naga Hills during dynastic struggles and the Burmese invasion and many of them were assimilated in the Naga society. This is the short history of the Ahom-Naga relationship.

The Ahom-Naga border was an ecological border along the foothills, separating the hills from the plains, porous to socio-cultural exchange and migration. Plainsmen could claim land along the foothills for cultivation and their Naga neighbours could extract tribute for offering “protection”. Neither claimed absolute/exclusive ownership. Moreover, the border was flexible as it changed with the balance of power between the hills and the plains and the degree of forest cover along the foothills. The British imposed rigid boundaries that not only halted economic exchange, but also disrupted political and socio-cultural ties. The British also froze identities.

Hereafter, the Nagas in the plains and Assamese in the hills retained their “original” identity irrespective of how long they stayed there. Unsurprisingly, after the formation of Nagaland in 1963, the Naga settlers in the disputed area were seen as “outsiders” occupying Assamese land.

Land encroachment

Both during the colonial period and later, the Nagas protested against the encroachment of “their” traditional lands for tea, timber, and railway projects. After the grant of statehood to Nagaland within the colonial boundaries, the Nagas “occupied” hundreds of square kilometres of the disputed territory with the support of the state government and insurgents.

The Nagas claim that they are defending their traditional territory against “illegal Bangladeshi” and other settlers encouraged by Assam. However, Naga settlers completely depend upon cheap migrant labour. Also, the Nagas have fought bitterly among themselves for control over the disputed territory. On the other hand, the Assam government claims that it settled flood-affected Assamese people in its own territory that was being encroached upon by Naga irredentists, who claim thousands of square kilometres of Assamese territory often far from the foothills.

Decades of occupation and counter-occupation have transformed large parts of the reserved forests along Assam-Nagaland border into a patchwork of densely populated Assamese and Naga villages that cannot be separated into mutually exclusive zones. It bears emphasis that the border dispute is not driven by ethnic or religious differences. Naga history abounds in cases of bloody inter-tribal conflicts over water resources and land. Most recently, Mao Nagas of Manipur and Angami Nagas of Nagaland fought over a timber-rich area.

The conversion of a flexible ecological boundary into a rigid modern legal boundary is the root cause of the problem. Growing population, deforestation, soil erosion and uncertain rainfall are pushing people of both states toward the relatively underpopulated and extremely fertile and timber-rich inter-state border.

The decline in Assam’s tea industry and the growing population of Adivasis of tea gardens has added to the long list of prospective claimants. People on both sides are now claiming absolute ownership of lands that might have had multiple and occasional users in the pre-colonial period.

Joint management of the ecologically fragile territory by local communities respecting shared use rights of people on both sides of the border is the only feasible solution.

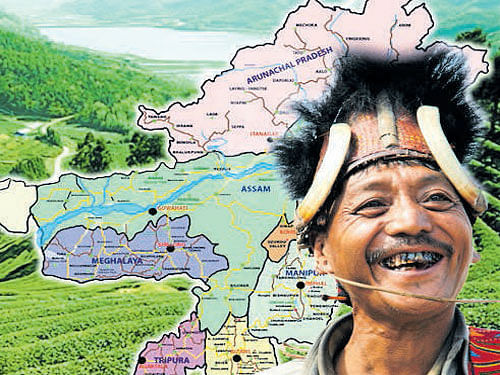

However, for a resolution of the dispute along these lines, the state governments have to withdraw court cases and stop encouraging competitive encroachment, while political parties, civil society and insurgents have to refrain from using this emotional issue to divert attention away from other problems. Similar solutions have to be explored to resolve Assam’s lesser territorial disputes with Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh.

(The writer teaches economics at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru)