Pointless temper tantrums are always silly; in politics, it is even more so, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi has probably figured out to his cost.

Instead of scoring a point against a three-time Assembly elections winner, a leading candidate for the chair of the next prime minister, Mamata Banerjee, beleaguered Prime Minister Modi ducked behind the barricade of institutions. It started with the Constitution, then the Central Bureau of Investigation and followed up by the bulwark of India’s bureaucracy to try and salvage his injured image and save face.

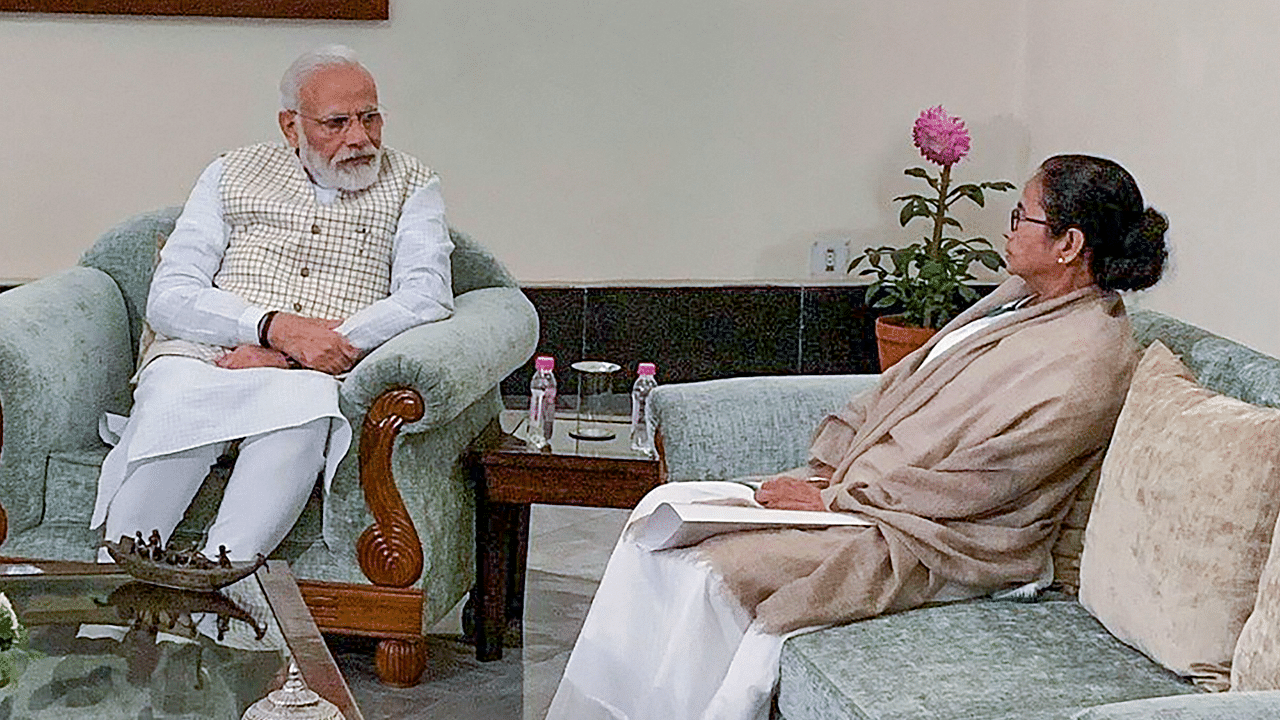

The third and doubtless not the last shot was seriously way off the mark. As the head of the national executive, Prime Minister Modi had scheduled a meeting with the executive head of Cyclone Yaas hit West Bengal, Chief Minister Banerjee.

To this meeting, he invited Governor J P Dhankar, who is not a functionary of the executive branch of government, and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s newly anointed leader of the legislative Opposition, Suvendu Adhikari. In doing so, the PM made a political move that backfired. Neither Adhikari nor the Governor had any reason to be part of the meeting, but Banerjee did not object. Instead, she came to it and left within minutes, handing over a report but not a request for funds or resources.

It was a politically neat manoeuver by Banerjee, who could not be faulted because she attended the meeting or at least showed up for it. She left citing a reason and asking to be excused. It was a snub. She had no intention of allowing Modi to put her and Adhikari on the same level. She dodged what would have been a politically humiliating moment and one that the BJP would have used relentlessly to claim that it was the equal of Banerjee, even if the party bombed in the elections.

The choice of Bengal’s just retired chief secretary and newly appointed Chief Advisor, Alapan Bandyopadhyay, to settle scores was a blunder. To have expected that Bandyopadhyay, a diligent IAS officer, would stay behind and pamper the PM, even when his boss, the CM, had instructed him to accompany her on the second leg of her tour of cyclone devastated areas, was politically and officially gauche. There was no way in which Bandyopadhyay could have flouted direct instructions without staging an insurrection, so overwhelming numbers of seasoned bureaucrats opine. “It’s not the done thing,” is the consensus.

Worse was to expect Bandyopadhyay to report for duty in New Delhi’s North Block on the day he retired. The order to quit Bengal and join the government at the Centre is where the PM disappeared behind the walls of the rules that govern the institution of the All India Services. Bureaucrats writing up the transfer order would have known, full well, that Bandyopadhyay could not officially move without being released by the West Bengal government. The question is, how did anyone in New Delhi think he could?

There are other points too that are of concern. Bandyopadhyay, a senior bureaucrat, should have been asked before he was ordered; the state government had to be requested to release him. None of this happened.

The PM’s pique is stamped all over the Bandyopadhyay incident. Trying and settling political scores by making a brouhaha over the actions of a bureaucrat is a loud and clear admission of having lost a fight and that too in bad spirit. The outcome is that Banerjee has won twice over and Modi has lost two times. The political embarrassment for Modi is huge.

To paint over the defeat, the BJP has to find a way to score a win against Banerjee. For now, it cannot. The unintended consequence of the Bandyopadhyay incident is that Banerjee has come out as a strong defender of her subordinates, who rewards loyalty, having made Bandyopadhyay chief advisor for three years.

The barracking of Banerjee began even before the counting of votes ended. The saga begins with the first shot fired against Banerjee for political violence before and after the polls. The BJP had a point, albeit weak but not unconvincing.

After losing the elections in Bengal, the BJP as a failed principal challenger, the principal opposition party in the state, a party that is in power at the Centre and has other resources at its command, did its best to destabilise the newly elected government.

It used the inevitable score-settling violence that is intrinsic to the state’s long-established political culture. Aided and encouraged by Governor Dhankar’s Twitter storm in the days immediately after the polling was over that law and order was spiralling out of control, and that it was on the verge of a breakdown of constitutional proportions, the BJP felt it was getting some advantage out of the narrative of hostility it had crafted.

The second shot was when the politics began to unravel, and pique became visible. Four political leaders, including two key ministers of the newly elected Bengal government, were arrested by the CBI, bundled into jail after bail was granted and then cancelled. After a week of courtroom battles, they returned home and got on with their jobs.

That Modi is not great at either governance or politics when times are tough is all too evident. He seems to have a predilection for losing the plot. And Bengal is his weakness. Working to oust Banerjee from power in Bengal and install a “double engine government” of the BJP at the Centre and in the state was a higher priority than staying ahead of the pandemic surge and so keeping it from spreading exponentially.

Nobel winner Amartya Sen has precisely pinpointed the catastrophic consequences of inappropriate chest-thumping. He said recently, “The government seemed much keener on ensuring credit for what it was doing rather than ensuring that pandemics do not spread in India,” which resulted in a daily infection rate that topped 4.5 lakhs for days and killed 4,500 people a day. Professor Sen was precise about the effect. “The result was a certain amount of schizophrenia,” he said.

The Supreme Court’s intervention was necessary to get the Modi government back on track, only after which a National Task Force was set up to sort out the disastrous supply problems of oxygen when the demand curve showed a steep rise. Post the Bandyopadhyay affair, the same court’s scathing statement that variable pricing of vaccines and a botched distribution plan violated the fundamental rights to equality and life guaranteed by the Constitution underscores that Modi was not focused on the job because his attention was elsewhere.

(Shikha Mukerjee is a Kolkata-based senior journalist and political commentator.)