With mounting criticism of the government’s inaction on deepening rural distress and the pressure of the upcoming elections, governments are clamouring to announce relief packages for farmers ranging from loan waivers to income-support programmes.

The big-ticket announcement of the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana which will transfer Rs 6,000 directly into the accounts of 12 crore small farmers with less than two hectares is not only grossly inadequate but also excludes a large swathe of the landless poor (56% of all rural households, according to the Socio Economic and Caste Census, 2011) that rely on casual manual labour. For them, many including the government may argue, there is the NREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005).

With all eyes on the upcoming election, it is perplexing why there is so much political silence on the potential role of NREGA — the country’s only legal wage-employment guarantee programme. The budget allocation of Rs 60,000 crore for 2019-20 is even lower than the total allocation of previous year.

As of now, four of the six drought-affected states have no funds to meet the demand for the next 30 days, let alone provide the additional allocation of 150 days per household that has been granted to drought-hit states and clear the Rs 6,500 crore in pending liabilities.

The NREGA was introduced with the specific goal of providing a buffer to the rural poor, particularly the landless, at times of such crises. Numerous studies by leading development economists in India and internationally, have shown that NREGA has served as a catalyst for rural transformation.

After stagnating for at least three decades, the growth in real rural wages (especially agriculture) picked up in 2007–08 after NREGA was introduced. The average growth rate of rural revenue jumped from 2.7% per year in 1999-2004 to 9.7% in 2006-2011. Around 40% of the five crore households employed under NREGA every year are from the Dalit and Adivasi communities.

Even self-confessed sceptics of the programme — Muralidharan, Niehaus and Sukhtankar (all professors in the US) — in a recently published paper, come to the conclusion that the benefits of a well-implemented NREGA are greater than a direct transfer like a Universal Basic Income. The “impacts” that economists have sought rigorous evidence for through countless studies, (which sometimes cost more than the pending wage payments in the entire block the study is being conducted in) have been clear to the NREGA workers across the country.

Is it that perplexing then that the rural poor across India, individually and collectively, have fought against all odds just to access this basic entitlement, even committing the audacious act of filing FIRs against the prime minister of the country?

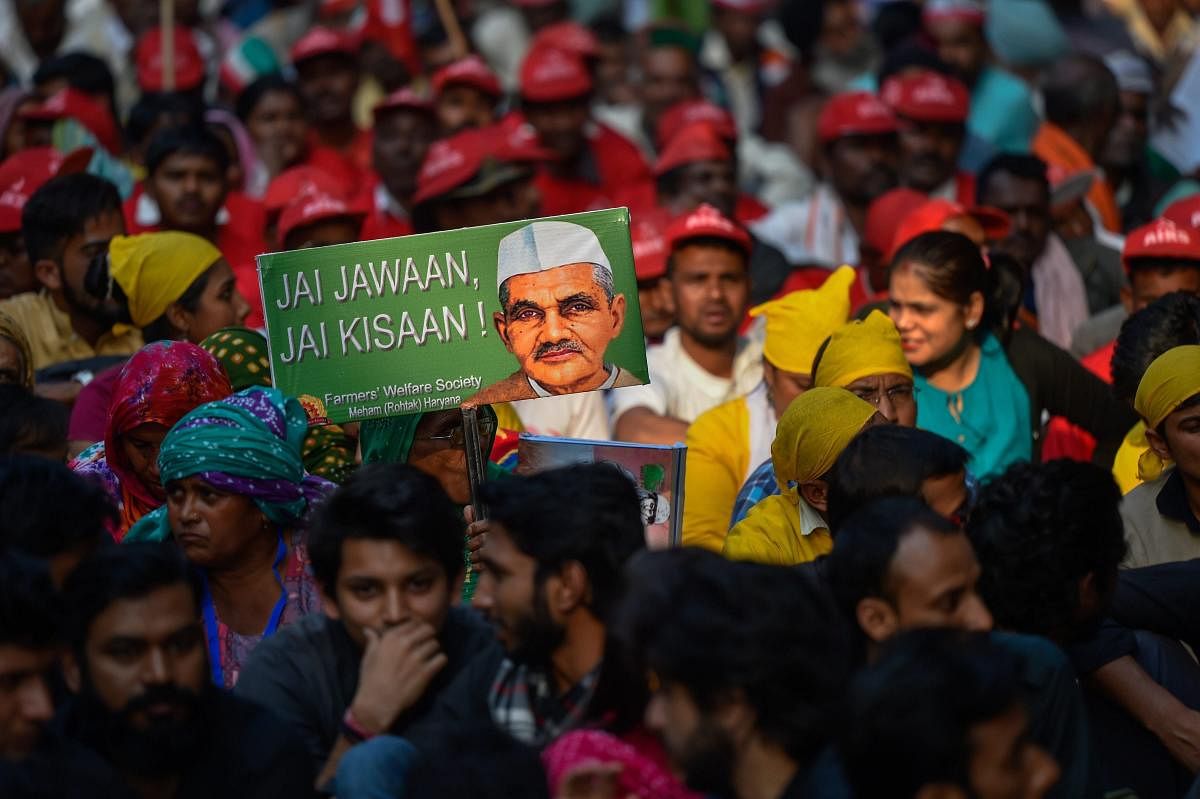

On February 28, 2019, thousands of NREGA workers filed FIRs against the prime minister and Union government under Section 420 (cheating and dishonesty) and 116 (abetment of offence) of the IPC at 150 police stations across 50 districts in nine states.

The FIR stated that Prime Minister Narendra Modi, “has been responsible for allotting less money” than the programme needs, “denying timely payments and causing hunger and hardship for workers like us.” Refrains of “chowkidaar chor hai” at political rallies may sound hollow, but when rural workers put their lives on the line and call the chowkidaar a cheat for violating the law and denying basic rights to the poor, it is a statement on today’s distressing times.

The complaint filed may seem naive to detractors but its rhetoric is powerful. For years, NREGA workers and collectives have been fearlessly fighting to get work under NREGA in different parts of the country. Take the case of Samaj Parivartan Shakti Sangathan, a collective of over 50,000 members consisting of mostly the landless poor who have been fearlessly fighting to get work under the NREGA for the last five years in Muzaffarpur district of Bihar.

Their relentless struggle to register demand for work, asking for fair wages and exposing corruption has been met with severe backlash by local political and bureaucratic elites. Part of this backlash is caused by the threat to established power structures and part of it can be attributed to implicit instructions to restrict employment provision in the absence of adequate funds from the Centre.

The issues that have brought NREGA to a standstill such as the acute fund shortage and massive payment delays have been regularly making headlines but to no effect. In mid-January, the Ministry of Rural Development made a token release of Rs 6,000 crore to states to silence the growing demand for funds.

Fresh employment

The fresh release has not been adequate to even clear pending liabilities due, let alone generate fresh employment for even a day. As per responses received via RTI, the Government of Karnataka is awaiting for pending dues to the tune of nearly

Rs 900 crore, even as rural workers in the state have been subject to a severe drought for the fifth consecutive year.

Why is it that NREGA does not attract the kind of public scrutiny and demands for accountability in the national-political discourse, when it creates such polarisation at the local level? We have to remind ourselves of the prime minister’s first statement on NREGA in Parliament in 2015, when he declared that his government would strive to keep NREGA alive only to serve as proof of the previous government’s failures.

Apart from reflecting poor statesmanship, the PM’s speech demonstrated clear intent. The poor performance of the programme today is not merely an outcome of weak political will but deliberate efforts to undermine it.

By introducing the poorly designed schemes like the PM Kisan Samman Yojana and the latest announcement of the Minimum Income Guarantee by the Congress, the political elite is only disclosing its own incapacity to respond.

Heightened public pressures on political parties at the time of elections should push political actors to step away from technocratic, off-the-shelf responses and re-centre political debate around questions of justice and equality.

(Adhikari is a PhD student of Brown University; Swamy is with Social Accountability Resource Unit)