The Congress Working Committee, the highest policy-making body of the grand old party, at its meeting on October 9, 2023, adopted the caste census as the party’s official plank. Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah, who participated in the meeting, promised that the findings of the Karnataka Backward Classes Commission’s Socio-economic and Educational Survey, commonly known as caste census, would be released at the earliest.

Congress leader Rahul Gandhi asserted in Prayagraj recently that the caste census is his “life’s mission” and he is “ready to pay a political price for it”. The question is, if that is the case, why is he not asking the Karnataka government led by his party to release the caste census?

The reason is that its implementation is not as simple as a CWC resolution or Rahul Gandhi’s discourse. It is fraught with serious risks of a political fallout. The census has set off concerns among the dominant Lingayat and Vokkaliga communities even as the Ahinda (Kannada acronym for minorities, backward classes, and Dalits) group is vociferously demanding its implementation. In addition, the State Cabinet is divided over the issue and Deputy Chief Minister D K Shivakumar, a Vokkaliga, is said to be opposed to the report which has not been made public.

The Congress and its government are caught in a Catch-22 situation on the issue. The alleged MUDA land scam which has engulfed Siddaramaiah and his 17-month-old government has added to the predicament.

Karnataka is the only state, next to Bihar, to have conducted a caste census. This was at the initiative of Siddaramaiah himself, during his first innings as CM, in 2015. The survey was conducted by the then Commission Chairman H Kantharaj, in 2018. The survey was a costly affair; a whopping Rs 160 crore was spent on it. Jayaprakash Hegde, as chairman of the last Commission, worked on the Kantharaj findings and submitted the report – titled Karnataka State Socio-economic and Educational Survey – in February 2024 to Siddaramaiah.

The government is yet to consider the report. Though Siddaramaiah announced that the State Cabinet would take it up at its meeting on October 17, the meeting could not be held because the ministers were busy with the State Assembly by-elections. So, any move on the contentious issue is unlikely before the polls, slated for November 13.

With reports that the Cabinet may take up the matter, those in favour and against the survey findings have become active. While the OBCs have demanded the report’s immediate implementation, the All India Veerashaiva Mahasabha has opposed it. Several ministers, former CMs, MPs, and MLAs across party lines who held a meeting on October 22 called for a fresh caste census. Mahasabha president and senior-most Congress MLA Shyamanur Shivashankarappa has said that the report “should be thrown into the dustbin”.

The Lingayat and Vokkaliga organisations are likely to come together to oppose the report. Besides the political leaders, mutts of both backward and dominant communities have also joined the issue, to support and oppose the report, respectively.

Why are the dominant communities opposed to the caste census? These influential communities fear losing their prima donna status in different spheres of the society in the state – they have been dominating the political, educational, financial, and social fields for decades – if the report is implemented.

They argue that the report is unscientific, not a population census, and was done a decade ago. The report is learnt to have concluded that the population of Lingayats and Vokkaligas is far less than what was assumed. The presumption till now has been that the dominant castes are also numerically strong, with Lingayats at 17 per cent and Vokkaligas at 15 per cent.

Oddly uneven numbers

What does the report say? The leaked portions, the veracity of which cannot be ascertained, say the total population of the state is 5.98 crore (and not 6.1 crore as per the 2011 census). It puts the population of Lingayats and Vokkaligas behind the Scheduled Castes and Muslims, which has ruffled the assertive communities’ feathers. It shows the population of SCs at 1.08 crore, Muslims at 70 lakh, Lingayats at 65 lakh, and Vokkaligas at 60 lakh. Lingayats and Vokkaligas claim that their number exceeds one crore each. The total population of the Ahinda group, as per the report, is around 3.98 crore while that of the dominant communities, including the numerically weak Brahmins, is at 1.87 crore.

The dominance of Lingayats and Vokkaligas in the Karnataka political landscape can be seen from these figures: of the 23 CMs, 10 were Lingayats and seven were Vokkaligas. Of the 33 ministers in the state now, 13 belong to these two powerful communities; eight Lingayats and five Vokkaligas are among the 28 elected as current state MPs; 44 Vokkaligas and 37 Lingayats got elected from Congress out of its total strength of 135 in last year’s Assembly polls. Lingayats have a strong presence in about 90 and Vokkaligas in 59 of the 224 Assembly constituencies.

Pitted against them in the caste census row is the Ahinda group which believes that the report presents a realistic picture and seeks its implementation. Siddaramaiah is seen as the unquestioned leader of the Ahinda group which had supported the Congress in the 2023 Assembly elections and this year’s LS polls. The party won 21 of the 36 SC-reserved seats in the 2023 Assembly polls while the BJP could win 12. The Congress also swept the ST seats, winning 14 of the 15. In the 2024 LS polls, while the Congress and the NDA won two SC seats each, both the ST seats went the Congress way.

The report has, thus, put Siddaramaiah and his government in an unenviable position. Can the CM take on the dominant communities and favour the depressed classes? At present, it looks like he can neither face the wrath of the powerful communities nor annoy the Ahinda group. The CM, and his government, are in for a tightrope walk.

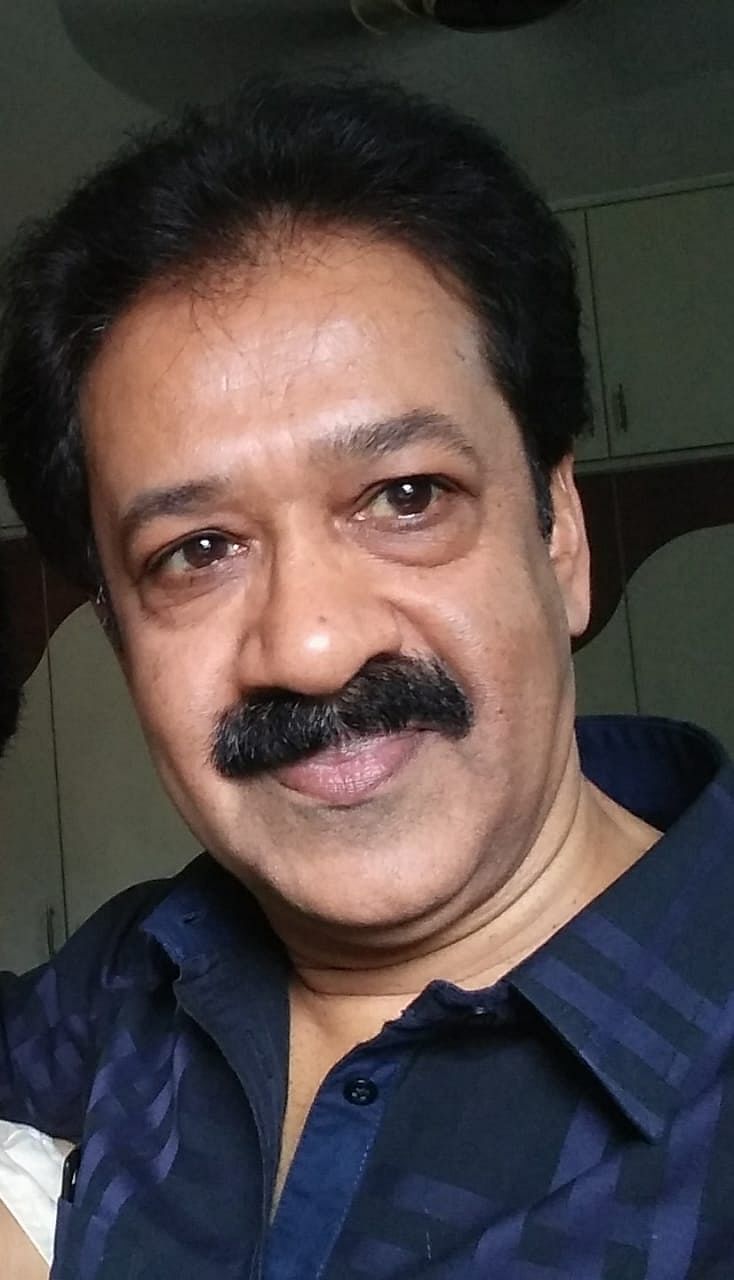

(The writer is a senior journalist)