Barely four months ago, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was on a roll. Fresh daily Covid-19 infections had declined appreciably, and India's vaccination programme was running smoothly. 'Vaccine hesitancy' was a problem undoubtedly, but criticism of the vaccination policy was largely absent. Everyone agreed that health workers and frontline workers, including police, paramilitary forces, sanitation workers, and disaster management volunteers, should be the first recipients.

Politically, the party exuded confidence in its prospects in the Assembly polls. Crossovers from the Trinamool Congress to the BJP in West Bengal appeared to assume tidal proportions. Worries remained for the party in Assam, but local analysts asserted that the Congress-Assam United Democratic Front (AIUDF) pact would benefit the latter and BJP and not the GOP.

In Kerala, 'metro man' E Sreedharan joining the BJP gave a shot in the arm, and the party overlooked its policy of excluding 75+ people from candidates' lists. In Tamil Nadu, the party firmed up its pact with the AIADMK early, and prospects to forming the government in partnership with local partners were good in Puducherry.

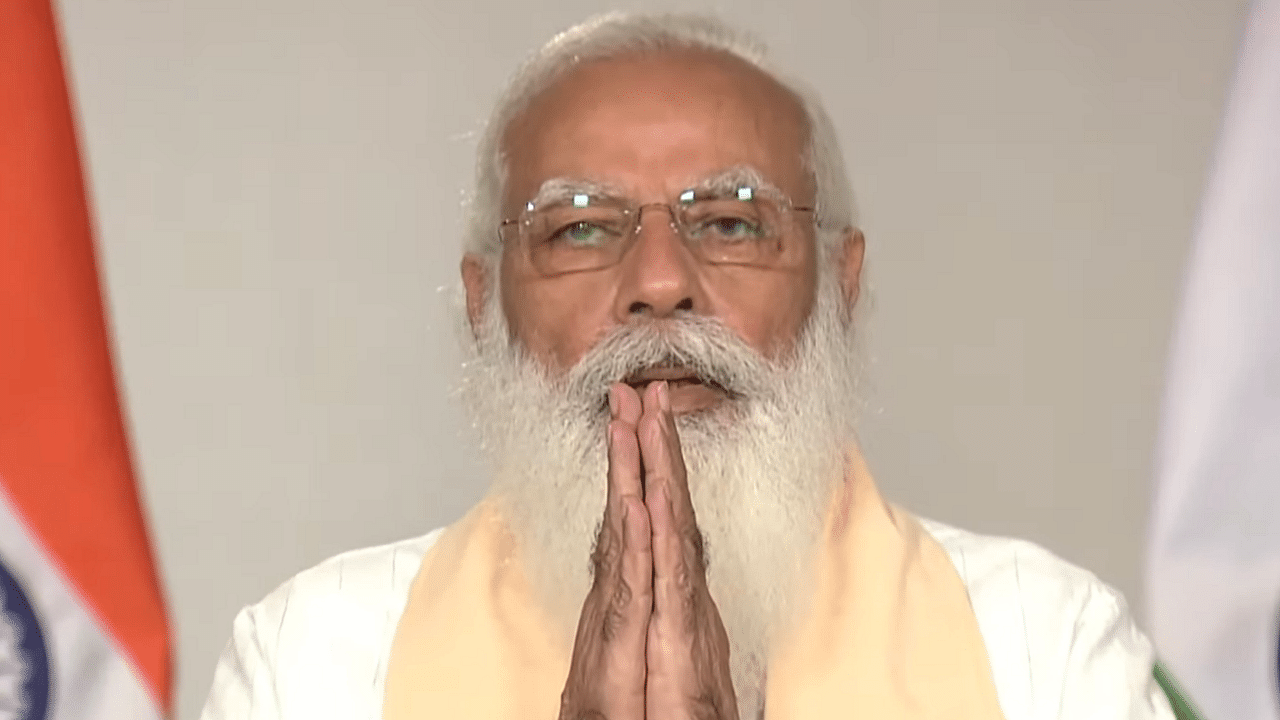

Against this backdrop, the BJP held its first office bearers' physical meeting during the pandemic in the third week of February. The resolution adopted at the meet mentioned Prime Minister Narendra Modi's name almost thirty times in a text of a bit above 3000 words - a mention every hundred-odd words. The resolution was steeped in sycophancy.

"It could be said with pride that India not only defeated Covid under the able, sensitive, committed, and visionary leadership of Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi but also infused in all its citizens the confidence to build an 'Atmanirbhar Bharat'," the resolution said. It also hailed his "tireless and ceaseless efforts in serving the people."

Four months on, the confidence has disappeared, and Modi 2.0 and his party jointly face a severe midlife crisis. Governance deficit, loss of people's trust in him, uncertainty over the pandemic, the economic problems confronting crores of people are not unexpected given the cyclical nature of anti-incumbent sentiment. Almost every government has faced such a crisis once past its honeymoon period.

But the way the party has unravelled in a few states is entirely unexpected. Within his party, murmurs of merriment at his visible discomfort are louder than ever before. From a leader who towered over others within the party, Modi has seen his authority erode in Uttar Pradesh with Yogi Adityanath infamously switching off more than his ear to a diktat.

With 'command route' not working, Modi tried out the 'pacifying mode'; on June 13, he tweeted the link of a more than 10-day old positive news report of an initiative of the Yogi government. "Very good initiative," the tweet, which tagged the UP CM, read.

In contrast to this, Modi had not publicly wished Adityanath on his birthday on June 5. Having failed in coercing Adityanath into inducting former PMO officer AK Sharma (who took premature retirement in January 2021) into his ministry with an important portfolio matching his administrative skills and experience, Modi is now trying a humbler way. He appears to have come to terms with working jointly with Adityanath till next year's UP polls. However, Adityanath is 'doing to him' what Modi 'did' a decade and a half ago to the BJP national leadership of that time - demonstrating autonomy.

A similar accommodative style is in evidence at the Centre. Modi and Union Home Minister Amit Shah have taken to hold consultative meetings with party lawmakers and ministers. Modi gets into this mode whenever under pressure.

In early 2019, before the emergence of the Pulwama-Balakot twin incidents as the principal electoral issue, the BJP conceded ground to the Shiv Sena while finalising the seat-sharing pact. For Modi, his ties with others in the party and among allies are inversely proportional to his 'winnability - the higher it is, the lesser is the concern for the other's ambitions and vice versa.

The BJP's woes are not restricted to UP. From the tiny archipelago of Lakshadweep to the streets of small-town West Bengal, BJP workers are up in arms against the central leadership for a variety of reasons. Furthermore, in Bengal, there was this dramatic development of Mukul Roy doing a ghar wapasi, just a day after the BJP controlled the political narrative on the day Jitin Prasada left the Congress to join it.

The worrisome part for the BJP, whether the events are in UP, Bengal or Karnataka, is that the writ of the central leadership is now running thin - the prabharis (state in-charges) are being systematically defied. The 'questioning from below' is against the grain of post-2014 intra-party functioning and gets intrinsically linked to the party's 'winnability'. Indeed, for the first time in Modi 2.0 tenure, doubts have risen at every level of the party about the stranglehold of the BJP in territories already under its control and its capacity to expand to new states.

The roots of the BJP's troubles lie in the perception that the PM has fallen short on the parameter of being an 'ace administrator', which his image-makers made him out to be. In the second wave of Covid-19, the situation got out of hand due to four factors. One, hubris of having 'defeated' the virus. Two, dismantling of temporary medical facilities created last year, like makeshift wards in banquet halls and redesigned railway compartments. Three, the government failed to ramp up medical oxygen supplies and ensure speedy distribution urgently.

Finally, the Centre came a cropper in responding to the emergency with the alacrity required. The hallmark of a good administrative leader is the capacity to tackle unprecedented and unforeseen situations. This is undoubtedly the gravest political and administrative challenge in the prime minister's career, and he cannot follow an existing script because the only one existing is a century old. Added to this is the lingering farmers' agitation that can cost heavily, both electorally and in terms of social alliances that the BJP built.

All of this has resulted in considerable erosion of public trust and faith in Modi. It will be long before the BJP peddles the slogan - Modi hai to mumkin hai - again. It is premature to ascertain if this loss of the public's confidence in Modi's abilities will have electoral implications in the future. But there is no denying that this critical period of lapse in Modi 2.0 was a significant factor in the BJP's failure to bag Bengal and a single seat in Kerala.

Undeniably, the BJP is still the largest party, Modi remains the most popular leader, and there is as yet no clear nationwide opposition. History, however, informs that alternatives emerge overnight because there are popular regional 'options' available, and these can join forces. There are also times when disenchantment with a particular leader reaches a level when the vote become a 'negative' one against her/him and not a 'positive' in favour of the (potential) challenger. Yet, the opposition, most notably the Congress, which remains the largest opposition party, has to be more focussed and hit the ground.

Comfort for the BJP and its leader lies in the fact that the Lok Sabha polls are three years away. It can hope that time will erase memories of personal, emotional, and economic loss. But this can happen only when there is dramatic containment of the pandemic, and the health and financial security of the people improves dramatically.

This is a colossal task before the BJP and Modi, and the current team doesn't inspire confidence to effect a turnaround. Already the consultative exercises and his 'accommodation' of Adityanath indicate that a more pragmatic Modi appears to be making an appearance, although he is also the master of misleading others with apparent actions. The next few weeks are critical and will indicate the likely mood of the people.

(The writer is an NCR-based author and journalist. His books include 'The RSS: Icons of the Indian Right' and 'Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times'. He tweets at @NilanjanUdwin)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.