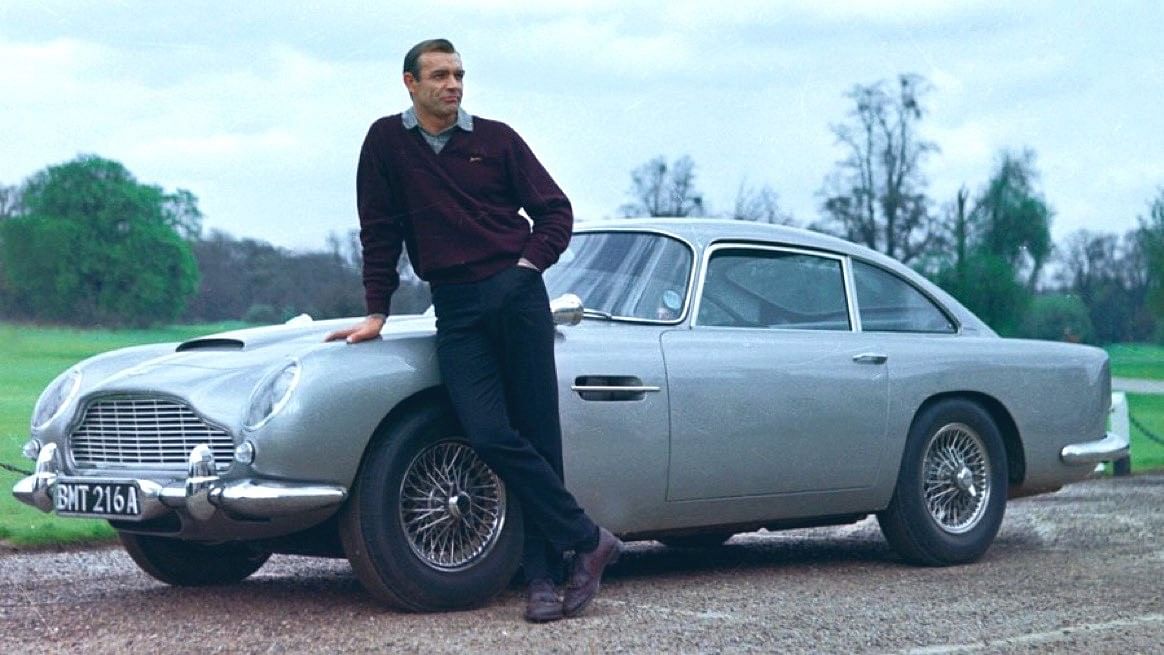

Sean Connery in his role as James Bond. Connery was the first actor to essay the part of the British spy, Daniel Craig being the latest.

Credit: X/@Super70sSports

By Max Hastings

“The name is Bond. James Bond.” It is one of the most famous catchphrases in the world, familiar in 50 languages. What a droll twist of fate it is, that while Britain’s importance in the world has shrunk immeasurably over the past 70 years, the soft-power influence of its most potent fictional export, the “licensed to kill” 007, has attained stupendous proportions.

This is one inescapable conclusion from a huge new biography of Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming, written by veteran literary biographer Nicholas Shakespeare. (It was just published in the UK and will come to the US in March.) Ever since the first Bond book, Casino Royale, was published in 1953, intellectuals — including Fleming’s own wife — have derided them. Yet I would argue that the books have real quality; that the author was a remarkably gifted storyteller who deserved his global triumph, though he died too soon — aged only 56, in 1964 — to enjoy much of the cash from them.

The international influence of Bond is greater than that of any other British product, including its Royal Family. Many national leaders have proclaimed themselves fans. Most famously, President John F. Kennedy and his publicists embraced the British agent as a symbol of action-man leadership, the image he sought to project of himself.

After Kennedy in 1961 publicly anointed From Russia With Love as one of his favourite books, the publishers ran an ad campaign that showed a single lit window in the otherwise blacked-out White House, and the caption: “You can bet on it he’s reading one of those Ian Fleming thrillers.” (So, it may be, was Lee Harvey Oswald two years later.)

George W Bush and Donald Trump have invoked 007 with enthusiasm. Ronald Reagan paid an effusive tribute, saying: “James Bond is a man of honour. Maybe it sounds old-fashioned, but I believe he’s a symbol of real value to the Free World.” Nicholas Shakespeare observes that some of these presidents spoke as if they believed that Bond really exists.

The Cold War Soviets, too, became obsessed with Bond — as an adversary, and set out to counter him in bookshops and on screen. Vladimir Semichastyny, who became boss of the KGB in 1961, promoted a cult of Russian fictional “hero spies,” such as Maxim Maximovich Isayev, in books written by Yulian Semyonov, of which the first was titled No Password Required. These went on to win huge Russian cinema and TV audiences.

Fleming, in the later books — as the Cold War grew less chilly — felt obliged to substitute an international master criminal as Bond’s nemesis in place of the Soviet spymasters of the earlier titles.

In 2009, a pair of American academics, David C Earnest and James N Rosenau, made the case that Fleming, through the Bond stories, anticipated globalization and the rise of villainous nonstate actors such as Osama bin Laden and the Colombian drug cartels as threats to Western society: “These groups thrive by exploiting the inability of states to cooperate and maintain control of translational technological, financial, commercial and migratory flows.”

It is a notable irony that today, President Vladimir Putin’s Russia acts more murderously at home and abroad than Fleming ever dared to fantasize about.

Few people dispute the quality of the Bond movies, especially the early ones starring Sean Connery. (True, there were some stinkers, and the treatment of women is disturbing by any standards.) Yet the books on which the screen versions are based have receded from the shelves of bookshops. Ever since Casino Royale, the highbrow crowd has derided them. “Snobbery with violence” and “soft porn for Cold Warriors” are among the discourtesies lavished upon them.

Early titles languished — in the 1950s, none of the first five sold more than 12,000 copies in hardback. Fleming said sadly, speaking of his wife’s wild extravagance: “My profits from Casino will just about keep Ann in asparagus though Coronation week.”

Fleming himself was a fascinating if tortured Englishman. He was born in 1908, one of four sons of Conservative MP Valentine Fleming. The family tree was dominated, however, by his grandfather Robert, who emerged from the humblest origins to become a major banker on both sides of the Atlantic.

He started his career at 13 as a clerk in a Dundee textile firm, and by 21 was managing its American holdings. In 1873, still only 28, he launched the Scottish American Investment Trust. In the years that followed, he became a major force in funding US railroads, borrowing in UK at 3 per cent and investing in the US at 7 per cent. He founded the London merchant bank that bore his name.

He became enormously rich, and in 1906 gave his son Valentine £250,000, equivalent to many millions today. When Valentine was killed in World War I, his widow, Eve, a ferocious character addicted to power over her sons, inherited absolute control of this fortune. Robert thereafter gave them no more money, so that while Ian and his siblings grew up amid wealth, they were at the mercy of their mother’s whims. (His brother Peter became a decorated soldier and a journalist, and wrote a classic travelogue in 1936 about a harrowing journey through Xinjiang titled News From Tartary.)

Ian attended Eton College like his brothers, but left prematurely, and became briefly an army cadet. Then he spent several years studying in Germany and Switzerland, and worked briefly as a journalist and stockbroker. His most notable early successes were with women, who adored his rakish good looks and cosmopolitan wit. His habit of sometimes propositioning a girl 10 minutes after first meeting her was rewarded with surprisingly many acceptances, though such advances might prove less popular in the 21st century. A friend said that his taste, like James Bond’s later, was chiefly “for tarts who looked like nice girls.”

World War II provided the pivotal experience of Fleming’s life. He was plucked from boredom in the City by Britain’s director of naval intelligence, Admiral John Godfrey, who decided that he needed a personal assistant who understood people and metropolitan life, rather than how to run a warship.

In the ensuing six years, Fleming travelled widely and learned enough of the secret world as a privileged spectator to lay a gloss of pseudo-authenticity on his later Bond tales. He went to America with Godfrey in 1941 and forged relationships with Sir William Stephenson, the Canadian who ran British Secret Service operations out of New York, and General “Wild Bill” Donovan, whom President Franklin D Roosevelt empowered to create the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA.

Fleming was a brilliant networker — many people on both sides of the Atlantic really liked him. I am sceptical, however, about Shakespeare’s claim that he became a major player in the intelligence world who exercised lasting influence on US secret activities.

Fleming found the war thrilling — though for him, it was also pretty safe. He founded a piratical commando unit called 30AU, which roamed Europe behind the allied spearheads, harvesting German secret documents. But was he a serious spymaster? I think not.

By the time he published the first Bond in 1953, Fleming had achieved practically nothing significant except to amuse himself, make love to many women, smoke innumerable cigarettes and learn a good deal about the world, especially its rich and smart bits.

Marriage to Ann, his long-serving lover and previously the wife of the newspaper tycoon Lord Rothermere, made them both unhappy. Financially, he lived from hand to mouth, and in 1946 was able to buy his beloved Jamaican bolt-hole, Goldeneye, only because a rich lover stumped up the £5,000 necessary.

Then came Casino Royale, which opened with a characteristic insider sentence: “The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning. Then the soul-erosion produced by high gambling — a compost of greed and fear and nervous tension — becomes unbearable and the senses awake and revolt from it.”

This hero lived the life about which his creator had always merely fantasized (except concerning the girls, that is). Bond was a winner at cards, a deadly shot, expert skier and underwater swimmer, gourmet, veteran of a hundred death-defying stunts, of which rappelling down the side of the Queen Mary at sea was not the most perilous.

The films instilled jokes into the Bond saga, whereas the books were humor-free zones — Fleming took Bond’s adventures as deadly seriously as did his hero. There never was such a real-life spy of any nationality, of course. But the author’s genius — and surely it is at least minor-league genius — is to make us, for an hour or two anyway, believe that 007 exists.

Bond’s celebrity was a slow burn. Fleming became widely known in Britain only in 1956. After the national humiliation of the Suez crisis, when invading British and French forces were obliged to withdraw from Egypt at the insistence of President Dwight Eisenhower, Prime Minister Anthony Eden borrowed the Goldeneye villa as a refuge in which to nurse his nervous breakdown.

The house and its owner suddenly became front-page news, though by a grotesque irony, just when Fleming became Eden’s landlord, his wife was in bed in Paris with Hugh Gaitskell, leader of Britain’s opposition Labour Party.

It is a peculiarity of Bond’s ongoing success in the 21st century that none of his worldwide audience seem to mind that he is British. He defies death at the behest of a spymaster based in the Thameside tower of Britain’s real-life secret service.

The keys to the triumph of the original books —achieved only progressively, as into the early 1960s each new hit fired readers to backtrack to earlier titles — were, first, that Fleming was an exceptionally gifted descriptive writer. His accounts of 1950s New York, Miami, Las Vegas; of grey and grim Moscow; of smoggy London and exotic Istanbul, are masterpieces of travelogue.

But more important even than the word-portraits is Fleming’s ability to make us believe absolutely in his own preposterous plots and villains. Putting the book down, we realize that it is an absurd notion that an ex-SS Nazi fanatic, Sir Hugo Drax, could have been authorized to construct a nuclear-tipped ballistic missile in Kent with the aid of 50 other impenitent Hitler fans, which Drax intends to fire at London. That was Moonraker.

No sane person could credit that Auric Goldfinger recruits a private army of American gangsters to pillage Fort Knox with the connivance of Moscow. But Fleming did. Even in 1955, it was a tad politically incorrect to conceive a black super-criminal operating out of Harlem with an army of voodoo acolytes, looting Jamaican treasure and doing favors for the Kremlin. But that was Live and Let Die.

Ann Fleming regarded the books with a contempt she shared with her smart friends. Even as the author got progressively more famous, he succumbed to melancholia as his health failed from a combination of drink, smoking and a poisoned domestic life. “Ann is always surrounding herself with intellectuals,” her husband said, “and intellectuals always make me feel inferior.” He especially loathed the artist Lucian Freud, who reciprocated.

As late as 1960, Fleming was obliged to thank his mother for her help in paying hospital bills — Eve eventually died only weeks before the author himself. We know that many stellar performers and artists in all mediums gain little pleasure from their fame, but Fleming’s story — and the suicide of his only son, Caspar, in 1975 — offers a masterclass in disappointment trending to tragedy.

He had experienced much sex but was no good at love. “Ah, scrambled eggs and bacon,” he said to a friend at breakfast, “the only two things in the world that never let you down.” A woman friend said that she once thought Fleming Byronic, but eventually decided that he was instead Falstaffian — “fascinating, but also ridiculous.”

Yet 007 lives on, the most famous Englishman in the world (fortunately, Fleming changed his first thought about calling his hero James Secretan). The first book initially earned its author just £219, but today a copy in good condition of the original edition of Casino Royale is worth £65,000.

Bond has proved impervious to time and changing values, remaining a potent symbol of a Britain that mattered on the world stage, appearing beside the Queen at the opening of the 2012 London Olympics. Boris Johnson, then the capital’s mayor, once parodied 007: Photos of Johnson made all the front pages, stranded on a zip line fluttering a union flag, in imitation of Roger Moore’s farewell role in The Spy Who Loved Me. (Who will be the next cinematic Bond, after Daniel Craig, remains unknown.)

The worse things get in the real world — the world of ravaged Ukraine, artificial intelligence and climate change — the more we crave the impeccably tuxedoed Bond in his vintage Bentley to solve everything for us. Rationally, we know that we ain’t going to get him. But we are allowed to dream, as did Fleming himself, in ways that continue to give us thrills seven decades on.