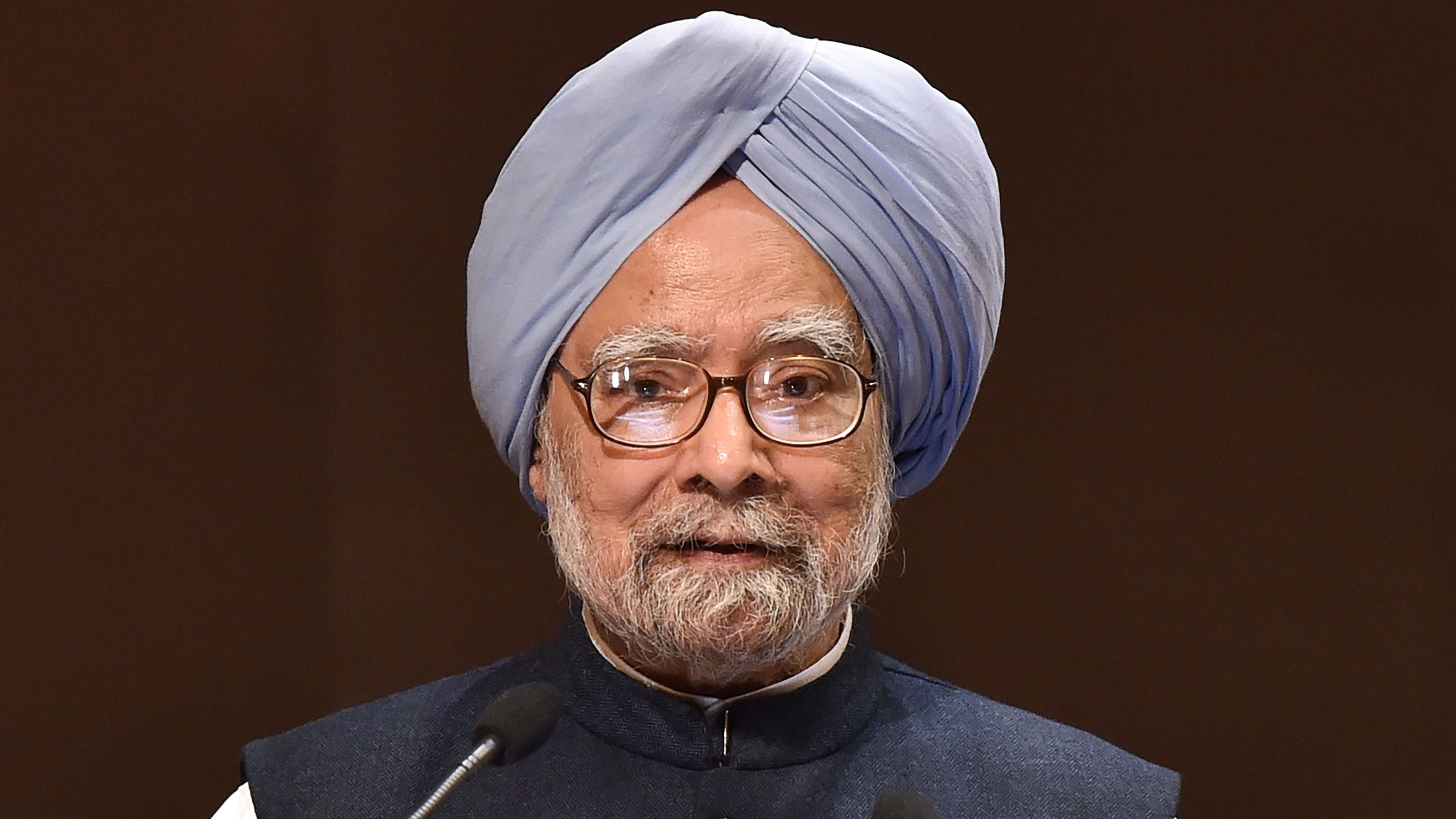

Former prime minister Manmohan Singh

Credit: PTI Photo

Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh who retired from the Rajya Sabha on Wednesday was made for the Upper House — erudite, wise, alive to the world but reflective and unobtrusive, clearheaded, and articulate. He distinguished the House with his presence, and his commitment was such that he attended it regularly even in his old age in a wheelchair. He never raised his voice or ran into the well of the House, nor violated a rule or norms of decency and civilised conduct. It is rare to find a parliamentarian with such a long innings and such a fine record when the standards of parliamentary conduct have deteriorated, and the Houses have become battlegrounds instead of forums for peoples’ representatives to talk, debate, and legislate. But Singh was not merely a parliamentarian made of better stuff.

His retirement marks the end of a long career of service to the nation in various ways — as prime minister, finance minister, governor of the Reserve Bank of India, finance secretary, consultant to prime ministers, economist, and academic. He left his mark on every position he held, and the absence of a person of his standing and calibre will make India’s public life the poorer for it. He changed history when as finance minister to Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao he liberalised the economy and took it out of the licence permit raj rut. Much of the economy’s performance since then has its roots in the new direction that he gave it, and the animal spirits that he released then. He became prime minister in 2004 in fortuitous circumstances, but had the longest stint as prime minister after Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi. Initiation of the rural employment guarantee scheme, enactment of the right to information legislation, signing of the India-US nuclear agreement, and consolidation of the economic changes he had earlier scripted stood out for their worth and his statesmanship. It was during his tenure that India started being reckoned as a power on the world stage. His second stint as prime minister was marred by charges of tolerance of corruption and indecisiveness. But the legacy that he left behind while in office is the most positive and the goodness at its core is not for easy erasure.

Retirement is not the occasion to assess a person’s place in history. Singh has only moved aside to let people and history pass, and to let the autumn seep into his life. But the man who steps aside is one of the most remarkable Indians of our times. He is also among the last of the Nehruvians, one who had a different economics, but a vision anchored in a saner and finer world.