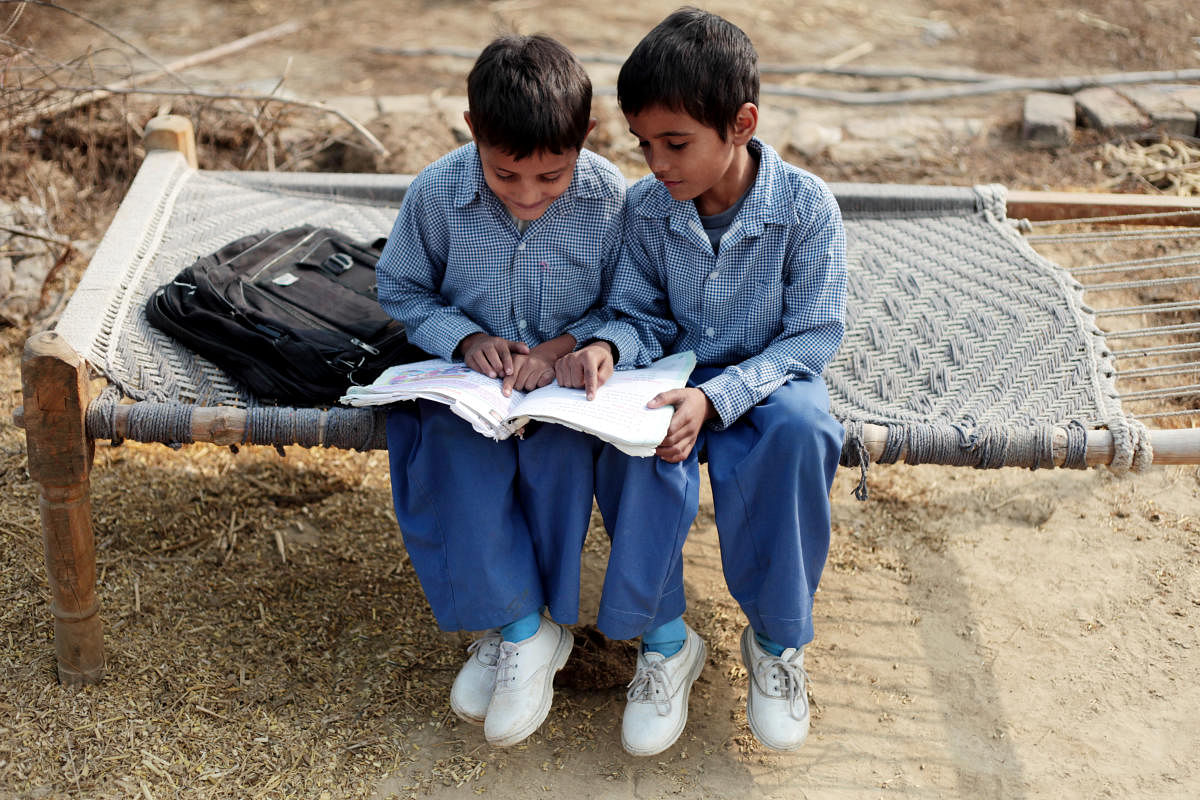

In just 20 years, the share of India’s children going to government schools has dropped from 71% to the current 52%. Nearly half of India’s school students attend private schools, with 70% of them paying monthly fees of less than Rs 1,000. Fuelling this dramatic growth of India’s private school sector are the aspirations of millions of middle and low-income families – India’s “next half billion” -- who believe that private schools will provide their children superior quality education and a passport to a better life. Nearly 40% of the children studying in private unaided schools come from the “aspiring” or “deprived” segments.

However, learning outcomes in private schools are not materially different from those in government schools. While India has secured near-universal access to schooling, it has faltered at the next step. India’s children are not learning. Alarming trends such as only half of Class V students being able to read Class II level texts (ASER 2018) point to an urgent need to focus on quality learning outcomes as the primary goal of education policies. Given the scale of the sector, improving learning outcomes in private schools needs to become an essential part of the human capital development agenda for India.

The dramatic shift towards private schools represents the conscious exercise of choice by parents. The time has therefore come for India to be more purposeful in empowering parents with the means to make informed decisions about their school choices. We must make it easier for parents to judge the quality of schools and strengthen their voice in demanding quality education for their children.

Why do parents choose to send their children to private schools instead of government schools, which are less of a financial burden? Their preference is partly influenced by the perceived failure of government schools; parents will likely choose private schools when the government school has teacher absenteeism and high pupil-teacher ratio. More importantly though, three key perceptions drive the demand for private schools: access to “English-medium” education, “better” teaching and learning, and a set of aspirational factors not linked to learning outcomes. And across these areas, there is a gap between perception and the reality.

English is at least one medium of instruction in 42% of private schools, compared to 10.4% of government schools. However, it is quite common to see schools that profess to be “English-medium” and with English textbooks using the regional language as the dominant mode of communication in the classroom: both between teachers and the students and amongst the students themselves. “Knowledge” of English is demonstrated by rote learning of some limited content. A 2019 survey by the Azim Premji Foundation in four Indian states reported that nearly 60% of the children supposed to be going to English-medium schools are actually studying in Hindi or Kannada. About 18% of the children attended schools that had textbooks in English but with teachers translating them into the regional language while teaching.

Parents also perceive that private schools have “better teaching and learning”. The Azim Premji Foundation study found that of the government school teachers, over 90% were graduates, 98% professionally qualified and on average, had 160 months’ experience. In the case of private schools, just 76% of teachers were graduates and 64% professionally qualified. In these schools, the average experience of teachers was 74 months.

Aspirational factors not related to learning -- such as computers, uniforms, CCTV cameras and school transport -- also influence parents’ choices. These aspects are usually emphasised in private schools’ marketing campaigns. The lack of consistent ways of reporting board examination results also makes it difficult for parents to get a complete and fair picture.

Philanthropic funding and eventually impact investing capital can play a vital role in supporting initiatives to build parent demand for quality learning.

Empowering parents to demand quality education has three dimensions: building greater awareness, increased transparency from the schools themselves, and improving the quality of engagement between parents and schools. In all these, the government and regulators must also meaningfully step in by making regulation more outcome-oriented instead of inputs-based. And philanthropic capital can play a vital role in laying the ground. Efforts by philanthropic funders can make the “invisible” factors of quality more visible – they can support awareness-building campaigns on what a “quality” education means and deployment of frameworks for greater transparency by schools. For example, publishing comparisons of school results in simple consistent formats and standardised ways of disseminating information on teacher competencies. They can also fund pilots of innovative constructs of engagement between the parents and schools that can serve to demonstrate “what good looks like.” Another area that philanthropic capital can explore supporting is independent third-party assessments of learning interventions.

The policy efforts, discussions and debates around improving education quality have so far mainly (and perhaps rightly) focussed on the supply side. The demand side – building the capacity of parents from the “next half billion” to understand and demand a quality education – is a tough problem. It’s a long journey, and critical to embark upon at the earliest, for our children’s future.

(Roopa Kudva is Managing Director and Namita Dalmia is Director, Investments, at Omidyar Network India)