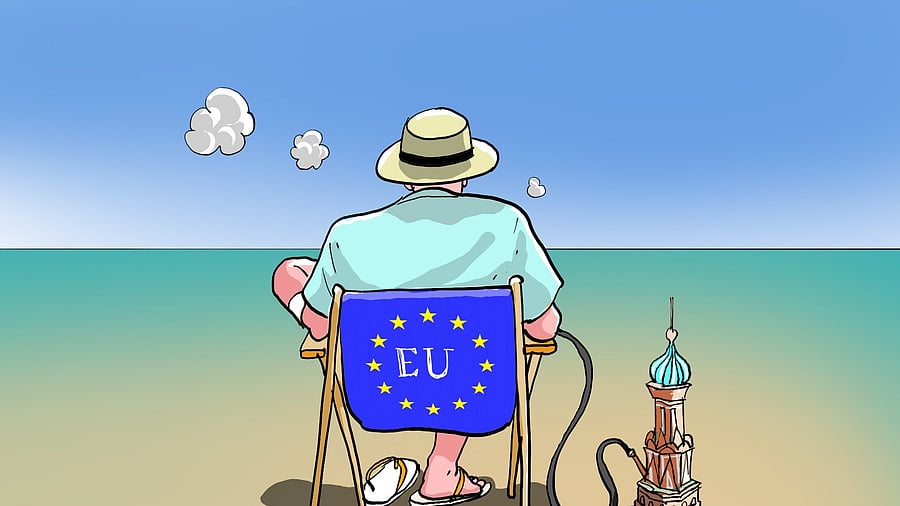

DH ILLUSTRATION

By Javier Blas

It must rank among the most preposterous examples of realpolitik. Nearly three years since Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine, Europe is still buying billions of euros of Russian natural gas. Absurdly, the Russian gas flows into the continent via a Ukrainian pipeline. Perhaps even more ludicrously, Kyiv charges its archenemy Moscow transit fees for using the conduit; in the middle of the war, the Kremlin duly pays the €800-million-a-year invoice.

The Kafkaesque flow, defying perceived political realities, is a sign of how Europe can’t live without Russian gas. Don’t say it too loudly, though, because nobody wants to hear it.

True, Europe is far less dependent on Russia than it once was. Before the war, the latter contributed 45 per cent of European gas imports; last year, its market share plunged to 15 per cent.Worryingly, not only has the reduction ended, but dependence is now increasing slightly. Year-to-date, Russia has about 20% of all European

gas imports.

I don’t blame the naysayers for pretending European dependency is over. Because if one acknowledges it isn’t, then the corollary is clear: Europe pays Russia for gas; Russia uses that money to wage war against Ukraine; in turn, Europe gives money to Ukraine to stop Russia. Thus the continent is bankrolling both sides of the conflict.

The Gas Route

Russian gas flows into Europe via three main routes. The first two involve pipelines. One runs throughout Ukraine into Slovakia; another travels via Turkey into Bulgaria. The third way is transport

as liquefied natural gas, a product that’s super-cooled for loading onto tankers and shipping around the world, very much like oil.

The European energy market’s reliance on Russian gas will be tested as the contract governing flows via the Russia-to-Ukraine pipeline ends Jan. 1, 2025. The deal is unlikely to be renewed in its current form as Kyiv, understandably, refuses to sit down with Moscow to renegotiate it. The matter is even more complicated by the fact that the entry point into the pipeline on the Russian side is in a town called Sudzha — now under Ukrainian occupation after Kyiv this summer made an incursion into the territory. Still, several attempts are underway to get either an extension of the deal or a new, politically palatable one that in all but name reflects today’s reality.

The Ukrainian pipeline is crucial for eastern and central Europe, particularly Slovakia and Austria. Italy, Czechia and Hungary also receive some volume. Earlier this year, the Austrian government warned of a “massive risk” for its energy security if the flow is halted. Vienna has maintained one of Europe’s oldest and deepest connections to Russian energy, and even today, it relies on the country for more than 80% of its gas imports.

The solution to keep the flow running via Ukraine involves Azerbaijan and a significant degree of commodity trading alchemy. The politically correct solution calls for the central Asian nation taking over the Ukraine-Russia gas contract to Europe. But there’s a catch: Azerbaijan is already pumping as much gas as it can, so to supply extra molecules to Europe, it would have to swap the gas with Russia. So we’re back to where we started.

Short of a complete halt, it is probably the least bad option. Notably, European Union Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson this month warned the continent about those machinations. “There are no excuses, the EU can live without this Russian gas,” she said. “This is a political choice, and a dangerous one.”

Simson is spot on that relying on Russia is a dangerous choice, one that involves a lot of political gymnastics. Gas is a diplomatic cudgel in the hands of the Kremlin. But she’s wrong in arguing that Europe can live without this energy source. Or, at the very least, she’s wrong that Europe can live without it and not pay a significant economic cost. Officially, the EU doesn’t aim to end buying Russian gas until 2027. And ultimately, one doesn’t hear that date spoken about much — a sign the deadline is at risk.

European gas prices have already climbed above 40 euros per megawatt-hour, the highest level in 10 months, and up 77% from the low point reached in February. So the continent needs to proceed with caution to avoid a further price spike.

The LNG Factor

The Russia-to-Ukraine gas is garnering much of the attention. But even more important is the flow of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). Here, most European nations pretend this isn’t a problem. Without this product, European nations would have to buy more from other suppliers, including the United States, Qatar, Australia and Nigeria, in turn competing with Asian importers for limited supply. The result will be a much tighter global LNG market and higher gas prices.

Russian LNG is becoming especially important for a handful of European nations. Spain, for example, is now bingeing on it. Madrid has gone from importing close to no Russian gas to now becoming its second biggest source of imports, only behind Algeria.

The development is surely an embarrassment for Teresa Ribera, the Spanish politician who’s set to become the next European Commission’s most senior official in charge of the energy transition. France and Belgium are importing, too, near record volumes of Russian LNG. Here, however, there are indications that many of those molecules flow beyond into a well-known market: Germany.

Europe’s options are limited. There is, to be sure, an argument in favour of continuing Russian gas purchases. The continent’s dependency is far less than it was before the war, and thus Moscow can’t wield its energy weapon with the same effectiveness as it once did. The money involved is less than before, too, reducing the help the Kremlin gets.

The cost of cutting usage to zero right now is too high: Prices would surge.

Economically and politically, that sounds about right. Morally, it is, of course,

repugnant.

What else is possible? Lowering European demand is difficult. Industrial consumption is rock-bottom, and it’s coming at a heavy cost of hurting manufacturing activity in the region — perhaps forever. European politicians could incentivise regional supply, but here the opposite is happening. While Europe still buys Russian output, most regional politicians are busy attacking the North Sea gas industry. In any case, domestic supply won’t help this winter, as it takes time. The same goes for more renewables.

So if Europe wants to keep prices in check, it must pay the moral price. It does stink — but so does war. At the very least, politicians should acknowledge it.