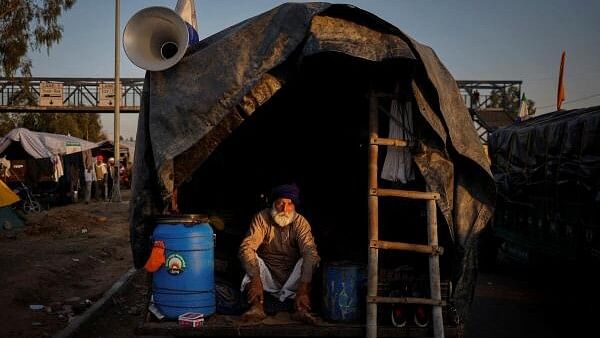

A farmer sits inside a tractor trolley as farmers march towards New Delhi to push for better crop prices promised to them in 2021, at Shambhu Border.

Credit: Reuters Photo

The nervousness of the Union government over the farmers’ agitation from Punjab is palpable, as it exerts pressure on X (formerly, Twitter) to take down accounts and posts related to the farmers’ protest. These accounts belong to farmers’ unions, activists, reporters, and even the Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee.

The Elon Musk-owned site has claimed that although it ‘disagreed with these actions’, it had to comply after receiving ‘executive orders’ from the Narendra Modi government. Failure to do so would have made the company ‘subject to penalties, including imprisonment’.

Earlier on February 22 morning, government agencies also raided the premises homes of former Jammu and Kashmir Governor Satyapal Malik, who has been an outspoken advocate for the agitating farmers. He has described himself as a “farmer’s son”. It is uncertain whether the sudden raids on Malik have something to do with the on-going farmers’ agitation, but the timing suggests it is.

Two organisations of Punjab farmers have been stopped at two border points of Punjab and Haryana at Shambhu and Khanauri. The Samyukt Kisan Morcha (Apolitical) led by Jagjeet Singh Dallewal and Kisan Mazdoor Morcha of Sarwan Singh Pandher were coming to Delhi. After the death of 21-year-old young protestor Shubhkaran Singh the agitation may take a new turn.

Up to now, two major farmers’ organisations that had not yet joined the on-going agitation — the Samyukt Kisan Morcha, representing 32 farmers’ unions in Punjab and the Bharatiya Kisan Union (Ugrahan) group — were under pressure to join after Singh succumbed to a bullet injury although the Haryana Police claims it has only fired rubber bullets. They had led the earlier agitation of farmers in November 2020-December 2021 forcing the government to repeal the three controversial farm laws. Now the two have decided to join the agitation at least symbolically by declaring a Black Day on February 23 and announcing a Mahapanchayat for larger consultation on March 14.

The Union government is nervous because the farmers are the only social group that has dared to take it on. Its ministers had maligned the protestors in 2021 as separatists (Khalistanis) and even as traders (arhtiyas) and middlemen rather than farmers. Yet Modi had to bow to their collective strength in 2021.

The Punjab farmers are brave, hardy, and patient, and have also shown that they are fearless. If the farmers’ agitation for minimum support price (MSP) for 23 crops continues, it could have serious consequences for the re-election prospects of Modi’s government.

Political bean-counters may claim that the agitation is limited to Punjab, a state that the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has already written off electorally. The party has bought itself insurance by allying with the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) of Jayant Choudhary in the Jat farming belt of Western Uttar Pradesh. It has also awarded the highest national honour, Bharat Ratna, to Jat leader and former Prime Minister, late Chaudhary Charan Singh. The Jat belt of Rajasthan (including Churu, Jhunjhunu, Sikar, and Hanumangarh) still appears ‘safe’ as the last assembly election did not indicate any specific impact of the earlier farmers’ agitation.

That only leaves the farmers of Haryana. The Jat farmers there are not with the BJP in any case. The party has positioned itself as the rallying point for mainly non-Jat voters for the last 10 years (hence a Punjabi Khatri, Manohar Lal Khattar became Chief Minister). Nevertheless, the BJP would be worried about the possible impact of the agitation on voters if the farmers’ protests prolong.

However, such political book-keeping often misses the wood for the trees. Pointers to the big picture developing from the farmers’ agitation are already emerging. It has disrupted the Ram temple narrative of the BJP as farmers’ issues take over mind-space, especially in North India, where the temple inauguration was expected to give the BJP an unprecedented lead over the Opposition.

Should the main SKM join the agitation in full force, it will not remain confined only to the farm sector. The SKM has strong links with banking and other trade unions which are smarting under the government’s policies of privatisation and the four unpopular labour codes passed by Parliament, though the rules have not yet been framed and notified.

The last time no one, not even his Cabinet ministers, had thought that Modi would be forced to do a U-turn on the three farm laws till even one day before they were retracted. The longer the agitation lasts, the more unpredictable the situation could become.

Even though the farmers have not yet come onto the highways, on February 20, the Punjab and Haryana High Court ordered that according to the Motor Vehicle Act, tractors could not ply on highways. Yet the court said nothing about highways being spiked, razor-wired and barricaded by the government. It went on to direct the Punjab government, “You should ensure that people should not collect in large numbers…they have right to protest but it is subject to reasonable restrictions.” The pre-emptive pronouncements of the judiciary in response to two PILs by private citizens, aim to prevent the farmers from travelling to Delhi with their tractor trollies, which double as caravans.

The farmers have also created an existential dilemma for the Aam Adami Party (AAP) government of Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann in Punjab. The two agitating unions have asked Mann to register an FIR for murder against those who shot Shubhkaran Singh in the head. If Mann agrees to file an FIR for murder, then it will go against the BJP government of Haryana; if he does not it will become impossible for him to step into the rural areas of Punjab. With the Centre asking him to maintain law and order in the state, the angry farmers may create a situation that could lead to the dismissal of his government by the Centre.

Up to now AAP has been playing both sides — but its balancing act has become increasingly difficult.

Should the other farmers’ organisations join the agitation beyond only symbolic support, the BJP’s electoral calculations, at least in North India may go awry.

(Bharat Bhushan is a Delhi-based journalist)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.