“I’m a fully-grown adult, but my mother still seems nervous whenever I leave the house,” Djigui, one of the thousands of protesters who took to the streets on June 29 in Nanterre, a working-class suburb of Paris, told me. “I can hear the crack in her voice when she checks to make sure I have my ID card or just says, ‘Watch out.’”

In Nanterre, on Tuesday last, this concern turned out to be a matter of life and death. Nahel M, a 17-year-old male of Moroccan and Algerian descent, was fatally shot by a police officer at a traffic stop, setting off a countrywide revolt over police violence and racism. Over the past several nights, protests have erupted in spectacular fashion. From Toulouse and Lille to Marseille and Paris, groups of protesters have sacked police stations and looted or vandalised scores of businesses, hurling Molotov cocktails and setting off barrages of fireworks at public buildings and the riot police. Nearly 1,000 people have been arrested.

The anger shows no sign of abating. The killing of Nahel M—which to many appeared more like a summary execution—exposed the most extreme form of the police violence that has long targeted communities of colour in France. It’s also acted as a catalyst for the discontent simmering throughout the country. For President Emmanuel Macron, it

was another blow to his authority, as he was forced once again to confront a France on fire.

Still, the killing of Nahel M might have ended up as little more than a secondary news item. Early press accounts portrayed the police officers as acting in self-defence, shooting an erratic driver willing to plough through officers to escape custody. This version of events would have placed the officers under the protection of a 2017 law, passed by Macron’s predecessor, François Hollande, that loosened police restrictions on the use of firearms in cases where a driver refuses to stop at an officer’s order. (This law has been cited as one cause of an uptick of fatal police shootings in recent years, which have risen to a peak of 52 deaths in 2021 from 27 in 2017.)

But cell phone footage taken by a bystander quickly shifted the narrative. The video, which surfaced soon after the killing, shows two officers standing beside the vehicle, one aiming his pistol toward the driver’s window at point-blank range. Though it’s unclear who uttered them, the words “I’m going to put a bullet in your head” can be made out before the car began to accelerate and the fatal shot was fired. Nahel M died an hour later.

The government’s first reflex was to portray a cautious sensitivity, in the hope of avoiding the type of street flare-ups that are often called a “contagion” of the banlieues—the economically depressed, multiracial urban areas that experience the brunt of French policing. “Nothing justifies the death of a young person,” Macron said on Wednesday, calling the actions of the police “inexcusable” and “inexplicable.” For Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne, the officers’ conduct was “clearly not in conformity with the rules of engagement.”

That’s probably as far as the president will go. After all, the government rarely takes opportunities to engage seriously with the problem of police violence. Macron has tended to attribute deaths at the hands of the police to the regrettable errors of individual public servants. In December 2020, when Macron made the relatively blunt concession that “someone with a skin colour that isn’t white is much more likely to be subjected to searches,” he was rebuked by France’s powerful police unions, whose members refused to carry out traffic stops and ID checks.

Part of the problem is Macron’s relationship to the police. Since coming to office in 2017, the president has relied on the police forces, cementing their central role in French political life. The spate of protests rejecting Macron’s various social reforms — most recently of the pension system — has been countered by a heavy use of the police. During the worst of the pandemic, police officers were the frontline executors of Macron’s stringent lockdowns and curfews. Now that the police forces are at the centre of a national controversy, it is no surprise that Macron’s hands are tied.

Then there’s the political pressure from the right. Trumpeting a presumption of “legitimate self-defence,” many figures on the right are calling for the government to unapologetically clamp down on protesters. The “poll of the day” for Thursday on the website of the conservative daily Le Figaro asked, “Is it time to decree a state of emergency?”

Behind that question lurks the memory of 2005, when weeks of riots after the deaths of two young men of colour during a police chase led to the use of France’s emergency powers law.

They may well get their wish. With Macron’s efforts to achieve social “appeasement” clearly in ruins, the hard-liners in his coalition, such as the tough-on-crime interior minister, Gérald Darmanin, are likely to be strengthened. At a cabinet crisis meeting on Thursday, Macron suggested as much when he castigated rioters for their “unjustifiable violence against the institutions of the republic.”

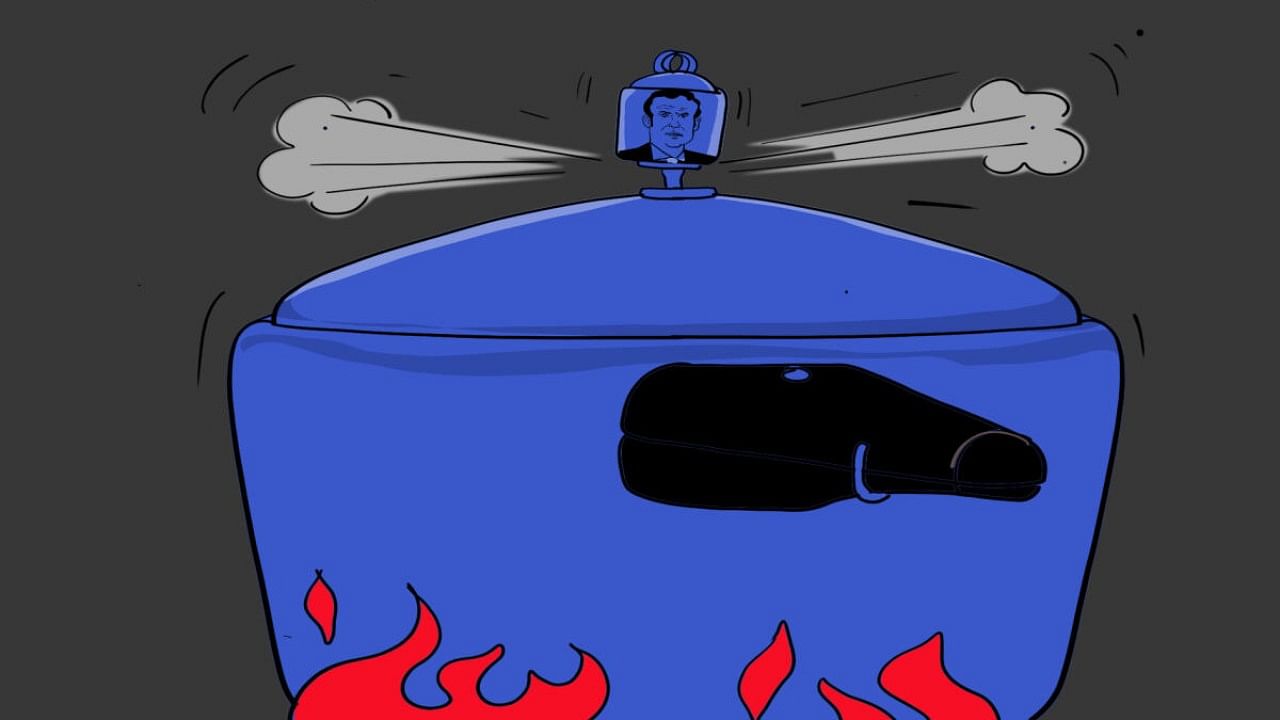

He’s half right. These protests are against the institutions of the republic, and one in particular. For many French people, especially marginalised young men of colour, Nahel M’s killing is the latest demonstration of the intrinsic violence of the police — and beyond it, evidence of a society that wants little of them and would rather they disappear. But they, and their anger, are not going anywhere. “We’re exhausted and just strung out by stories like this,” Djigui, the protester, told me. “For years, France has been like a pressure cooker.”

This week, it exploded.