The one area where there has been exceptional consistency and accentuation by the successive Modi governments is spending on transport infrastructure like roads and railways. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways and Indian Railways are allotted Rs 2.58 trillion and Rs 2.4 trillion, respectively, as capital expenditure (capex) in FY 24, out of the total capex outlay of Rs 10 trillion. That is, about 50% of the capex was allotted to the two ministries of roads and railways in FY 24. Since 2014, the allocation of capital expenditure on these two sectors has seen an unprecedented increase.

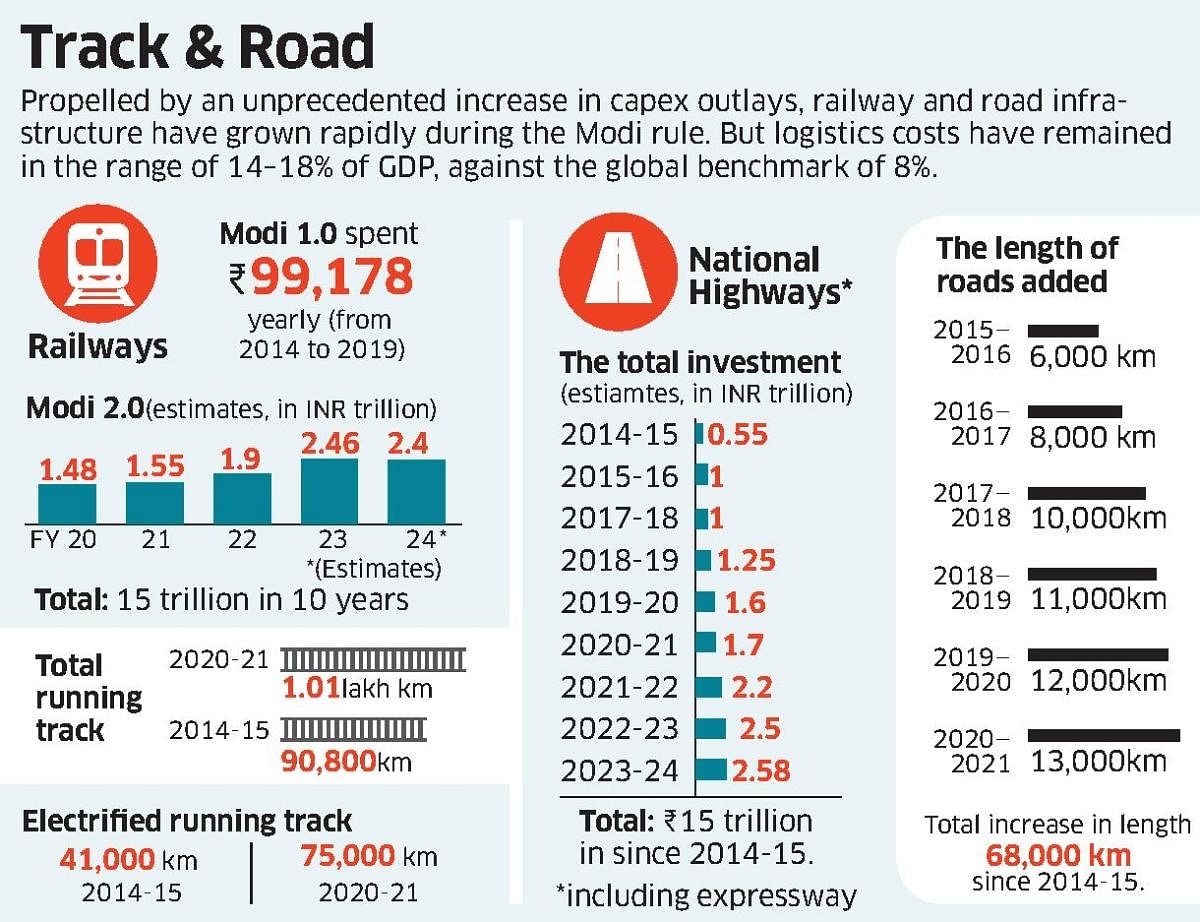

First, consider the railways. Against the average yearly spending of Rs 45,980 crore during 2009–14 under UPA, Modi 1.0 spent Rs 99,178 crore annually. Over the last 10 years, the Modi government has spent approximately Rs 15 trillion, with an annual increase in allocation. This kind of increased allocation is much beyond Wholesale Price Index (WPI) inflation. As a result, the total running track increased to 1.01 lakh km in 2020–21 from 90,800 km in 2014–15, and the electrified running track increased to 75,000 km in 2020–21 from 41,000 km in 2014–15. The output in terms of improved rail infrastructure is evident.

The question is whether the Modi government’s Rs 12.5 trillion investment in Indian Railways has provided the necessary impetus to railway traffic and revenue.

The railway passenger traffic (including both suburban and non-suburban) decreased from 1,147 billion PKM in 2014–15 to 590 billion PKM in 2021–22, which is understandable given the setback created by the Covid-19 pandemic.

On the contrary, this reduction in passenger traffic should have helped the Indian Railways improve its finances, as, on average, it has been subsidising its fares by about 50%. However, the revenue-earning railway freight traffic increased from 682 billion TKM in 2014–15 to 872 billion TKM in 2021–22 at a CAGR of 3.57%. When the railway tracks were freed from IR’s operation of fewer passenger service trains, IR should have grabbed this opportunity to scale up its freight traffic significantly.

The High Density Network (HDN) of Indian Railways has been carrying about 120% to 200% of its capacity since the 1990s. As per the World Bank estimates, in emerging countries, freight traffic would increase by about 1.25 times that of GDP growth.

The sub-optimal growth of revenue-earning freight traffic by IR over the last eight years has led us to surmise that the huge capital expenditure on railway infrastructure since 2014–15 has facilitated IR to reduce the overload and congestion of its tracks on HDN to some extent but not to increase its freight traffic or revenue.

The very nominal increase in rail freight traffic since 2014–15 shows that IR has not gotten its act together. The recent CAG report also highlighted the same. Because transportation costs account for a significant portion of logistics costs, only when freight traffic shifts to rail will logistics costs be reduced.

Then comes the National Highways (NH), which includes expressways. The total investment in national highways has been close to Rs 15 trillion since 2014–15.

The length of roads added to the National Highways since 2014–15 is about 68,000 km. Taking advantage of improved road infrastructure, freight and passenger movement by road has been increasing slightly exponentially, and this has essentially resulted in a modal shift of freight and passenger traffic from rail to road. As a result, such a massive expansion of the NH/Expressways network has not reduced the logistics costs.

The Economic Survey 2023 admits that the logistics costs in India have been in the range of 14–18% of GDP, compared to the global benchmark of 8%. The introduction of e-vehicles for both passenger and freight transport may reduce the operating cost as electricity is much cheaper than diesel and petrol. But there is a caveat. The upfront investment in electric vehicles is huge, and when that is accounted for in the logistics costs, the logistics costs may not decrease.

Although the government has spent equally on both rail and road transport infrastructure, it appears that IR did not turn this huge investment into a business opportunity. Spending on infrastructure has the maximum multiplier effect of 3, which is not achieved in any other spending by the government and hence falls under constructive spending.

However, in any pattern of investment, there are four stages: input, processes, output, and outcome. The government’s huge spending on road and rail infrastructure has worked well in the first three stages. Reduced logistics costs should be the outcome of this huge investment.

The Gati Shakti scheme was introduced with the aim of seamless integration of the movement of goods at reduced cost and time, involving about 23 ministries and departments. The synergies that have been aimed at by the Gati Shakti scheme between various ministries of the central government and state governments do not seem to have happened.

Although FY 2023–24 may be the last year of the Modi 2.0 tenure, the government may have to think about forming a ministry of Gati Shakti to coordinate

the efforts of various ministries

and departments.

The reduced logistics costs would moderate the increase in WPI first and then CPI. It is as critical as the efficacious use of the infrastructure created as much as the creation of physical infrastructure.

(The author is a Transport Policy expert.)