If justice is about the realising of rights and of fairness, the world order and the global economy have failed to deliver either justice or its sustainability to the gassed survivors of Bhopal.

From a liberal perspective, what justice demands of the advantaged is not that they should not abuse their privileges and superior bargaining position against those who, lacking basic rights, opportunities or economic bargaining power, are at their mercy. The lesson from Bhopal is that powerful states will not treat others equally if even human disasters seem likely to harm their vital interests. The global order of things is not set in the Rawlsian “original position”, which is something akin to the Hobbesian state of nature, where, behind the “veil of ignorance” or an ideal situation, a conception of justice allows people to spell out, beyond personal morality, their natural duty to remove injustices.

John Rawls, 20th century’s pre-eminent philosopher, affirms that well-off societies have duties to assist other societies to escape the burdens that oppress them and he believed that under some circumstances those duties might require international transfer of wealth. The goal, in that view, is to eliminate injustice and to guide change towards a fair basic structure. One position taken by Rawls is that the sources of poverty are largely to be found at the domestic level so that any enduring improvement must come about through local changes that outsiders are not usually in a position to effect. This is true to a great extent — the Indian governance structure perpetuates deprivation in every sphere in which the poor and marginalised have no access to decision-making, a position made more hopeless by their lack of empowerment.

But in a globalised world, in which it is assumed there would be equitable approaches to issues and problems concerning all across national boundaries, global inequalities continue to increase with the hegemony of neo-liberal conceptions of society and economy. It is also in a globalised world that there are greater opportunities for, and the incidence of, transnational harm which reflects what Henry Shue has called “export of hazards”.

The Rawlsian conception of justice falls flat under the crushing weight of the global order that, no less different from the domestic arrangements, exacerbates existing inequalities. Otherwise, how is it that the Indian government could agree to and accept a one-time compensation of $450 million by Union Carbide Corporation for the Bhopal victims and their survivors?

This iniquitous order has been imposed by the governments of rich countries whose people, in the Rawlsian view, have a duty — deriving from the duty not to harm — to reform the global order and perhaps to compensate for its damaging effects. But Rawls’ preferred “duty of assistance” does not effectively remedy the considerable disadvantages poorer societies suffer under fundamentally unjust international structures that include multinational corporations. It cannot be a modest duty of assistance to lesser-endowed people.

Fulfillment of obligations

In the case of the survivors of the world’s worst industrial disaster, caused by the criminal neglect of an American firm that manufactured deadly chemicals, the US government (it was amusing to watch a State Department spokesman speak on behalf of Union Carbide) and the corporation in question must do more than just the perfunctory duty of disbursing small change. The international circumstance of justice warrants fulfillment of obligations not just by minimal transfers from well-ordered peoples to the less advantaged, but by protecting a full range of human rights regardless of where those who suffer them reside.

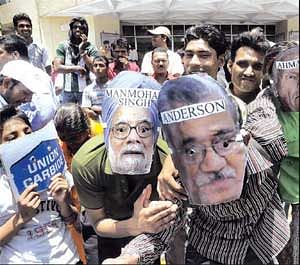

Even though it might seem a contentious argument (since some might argue that moral obligations do not fall properly on those who have not caused deprivation), it is undeniable that powerful actors — states and corporations — are more obviously able to shape and reshape indefensible inequalities. Regardless of how indifferent, callous, vain, corrupt and collaborationist India’s leaders and its decaying institutions are or might appear to be, Indian lives, like American lives, do not come cheap. There is not an iota of doubt in the minds of the people that the Bhopal verdict, which was an outcome of a corrupt political, bureaucratic and judicial culture, has heaped unimaginable indignities and cruelties on a generation of poor and maimed.

More than 200 hundred years ago, a lone Edmund Burke could seek the impeachment of Warren Hastings in the House of Commons for “high crimes and misdemeanours”. Burke went on to move the impeachment motion against Hastings “in the name of the people of India, whose laws, rights and liberties he has subverted; whose properties he has destroyed; whose country he has laid waste and desolate”…and “in the name and by virtue of those eternal laws of justice which he has violated…in the name of human nature itself, which he has cruelly outraged, injured and oppressed, in both sexes, in every age, rank, situation and condition of life”.

When the time has come to punish another Warren - Warren E Anderson - the Indian people cannot expect an Edmund Burke among its vain and corrupt leaders who work their offices not so much from behind a veil of ignorance. In Bhopal’s tragedy, India’s leaders from all political parties have compromised with crime. Like Anderson, they stand accused of exercising tyranny, and in the eyes of the people they stand impeached of honour for violating justice.