As we in India enter another election season, it is also an opportunity to draw attention to the challenges that China poses to our national security interests. If one were to pick just the last fortnight, there are at least three developments that draw attention to the inadequacy of India’s responses, or of its relative absence from the conversation.

The first development of note came on March 30, when the Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs issued a fourth list of ‘standardized names’ of places within Indian territory in Arunachal Pradesh. This list is the longest yet with some 30 names of administrative units, villages, towns, mountains, water bodies, and so on. The Chinese are engaged in ‘lawfare’ — shifting the global narrative on India’s territorial integrity and borders not by direct confrontation, but by seemingly legitimate exercises as ‘standardization’ while other countries remain largely unaware of the dispute between India and China.

The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) has been lazy in trying to dismiss this Chinese action as not materially affecting the situation on the ground. China’s radio and television networks, traditional news outlets, and social media handles are far more global in reach and in numbers compared to any by India, and so, the MEA’s position is not tenable — China’s action might not affect the situation in Arunachal Pradesh itself, but it does have a global impact in legitimising its claims where ignorance reins about India’s claims, or at the very least, in introducing doubt about India’s claims.

By contrast, one can only surmise that the Union government is trying to distract attention ahead of Lok Sabha elections from the serious developments at the Line of Actual Control (LAC) between India and China by raking up the issue of the Katchatheevu island between India and Sri Lanka — an issue that had been settled by bilateral agreement in 1974. Ironically, New Delhi is following Beijing’s example of ignoring bilateral treaties and opening up disputes where none existed previously. In the process, it also creates an opening for forces in Sri Lanka inimical to Indian interests to revive their bogey of Indian pressure on Colombo, and to play the China card.

Missing in Action

The second development came late last week when Australia, Japan, the Philippines, and the United States conducted their first joint patrol in response to violent incidents between Manila and Beijing in the South China Sea, particularly around Scarborough Shoal and the resupply missions to a Filipino vessel stuck in the Spratly Islands. Not unrelated, there are reports also emerging that the AUKUS submarine partnership between Australia, Britain and the US will expand to bring in Japan. The key point here is how India is not part of these initiatives.

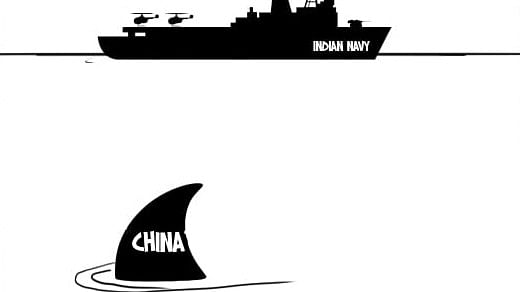

While External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar was in Manila recently declaiming India’s support for the Philippines’ maritime rights and national sovereignty under international law, the time is increasingly at hand when India must move beyond rhetoric — even if such rhetoric, too, represents progress — to actually committing to the practical defence of international law. The Indian Navy exercises with the Quad navies and is involved in anti-piracy operations in the northern Indian Ocean; but, it is time that it got the resources to build up and expand its security footprint in other oceans not just in support of friends, but also to mirror and counter the expansion of the Chinese navy. China’s pressure on the LAC should not distract us from this objective.

‘Neighbourhood First’?

The third development constitutes a series of recent visits by leaders and senior officials of ASEAN countries to China. This is not something particularly out of the ordinary, and that is precisely the key point here — the sheer density of visits and engagements between China and its neighbours, including those with which it has serious territorial issues ongoing.

During his meeting with the Chairman of the National Assembly of Vietnam, Chinese President Xi Jinping called the bilateral relationship one of ‘comrades-plus-brothers’. While their maritime disputes were discussed, the Vietnamese leader was also keen to improve and expand economic engagement between the two countries, including transit trade through China, border trade, and Chinese infrastructure development projects in Vietnam.

For all of India’s decades-long closeness to Vietnam given their common challenge from China, the depth of the relationship still leaves a lot to be desired. Unlike Pakistan, which has no economic dependence on India, Vietnam is heavily dependent on China. Even as it manages to stay hard-line on territorial disputes with its smaller neighbours, Beijing has expanded trade and its economic presence in neighbouring economies, undermining their ability to mount a serious challenge against Chinese interests.

There are lessons for India to learn from the way China prioritises relations with its neighbours. China and ASEAN are each other’s largest trading partners, while China is also the largest trading partner for nearly all of India’s neighbours in South Asia. The Narendra Modi government’s ‘neighbourhood first’ policy has gone some distance in building up neighbourhood connectivity but it has largely operated in fits and starts, and crucially, people-to-people interactions remain extremely limited . India is nowhere near knitting the region together in the manner of an ASEAN given the state of ties with Pakistan. This allows China to continue its ingress in South Asia.

In each of these cases, there are different ways in which India must react to, respond to, or even learn from Chinese actions.

An important pre-requisite, however, is for the Union government and the public to honestly acknowledge the challenge China poses to India’s foreign policy and security interests in its near and extended neighbourhood. Whether the government chooses to address issues of accountability on China policy in this electoral cycle or on some other occasion, the China challenge will only continue to grow and leave increasingly less room for India to sit on the fence, to wait to tackle the problem, or to ignore it altogether.

Rather, New Delhi must allocate greater resources to capacity-building on not just China, but also on its wider neighbourhood, including for the shaping of international narratives involving China. It must also commit to building more meaningful partnerships with neighbours and friends.

(The writer teaches international relations at the Shiv Nadar University, Delhi NCR)