A crucial determinant of the Sino-Indian border conflict is strategic communication and its interpretation. Prime Minister Modi’s Mann Ki Baat of June 28 suggests that no lessons have been learnt from the past – that maintaining a distinction between domestic politics and foreign policy is a necessary condition to avoid conflicts.

Modi said, “…the world has seen India's strength and commitment to protect its sovereignty and borders; in Ladakh, a befitting reply has been given to those eyeing our territory…” During the all-party meeting on June 19, Modi had said, “neither has any outsider come into our territory nor is any outsider on our territory.”

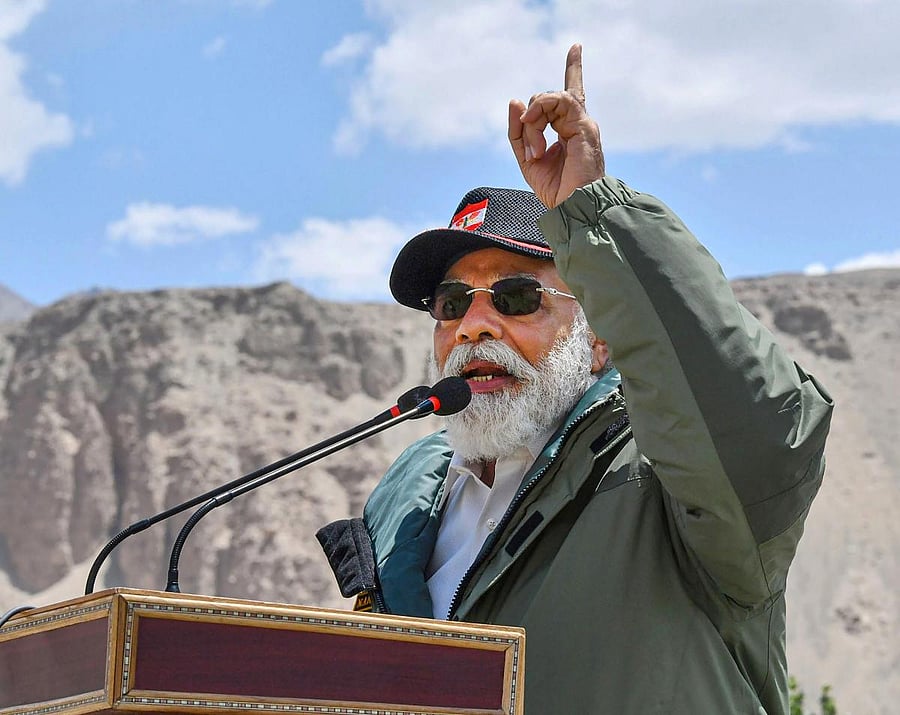

Following the violent clash along the Line of Actual Control at Galwan Valley on June 15, Prime Minister Modi’s visit to Leh on July 3 amidst ongoing military-level talks aimed at de-escalation was in Beijing seen, instead, as a signal of intent to escalate. Following this visit, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson stated, “India and China are in communication and negotiations on lowering the temperature through military and diplomatic channels. No party should engage in any action that may escalate the situation at this point.”

Prime Minister Modi’s Leh visit underscores the relevance of political will and military power in the present stand-off. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, too, had followed a similar course, which led to an undesired outcome of border conflict with China.

While Nehru may have wished for peaceful resolution of the border question, his hardline approach and statements in Parliament presented him as dubious and unpredictable to observers in Beijing. Then, as now, Opposition parties are demanding that the government call out China as the aggressor.

A combination of factors – failure of China’s economic and social campaign (Great Leap Forward), Nehru’s forward policy, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Tibet revolt, and misinterpretation of strategic communication led to the irreversible damage to Sino-Indian ties in 1962.

Leaders in a democracy, such as Nehru and Modi, feel the need to present themselves as strong to their electorate, irrespective of the demands of the overall strategic situation. Else, they are portrayed domestically as being weak by the Opposition parties.

Chinese analysts have identified Hindu nationalism, the need for domestic stability amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, economic development, the geopolitical challenges arising out of China’s rise, and the pursuit of absolute security in South Asia and the northern Indian Ocean region as the logic behind India’s “aggressive behaviour”, (Hu Shisheng, “The behavioural logic behind India’s aggressive behaviour”). The relative difference between the two countries in Comprehensive National Power is further seen as an explanation for India’s approach.

Both India and China have remained steadfast in seeking peaceful resolution to unresolved issues between them and, in the past, have jointly put forward innovative ideas and principles, such as the Panchsheel Treaty. Between 1993 and 2013, India and China signed five agreements to ensure maintenance of peace and tranquillity, confidence-building measures, working mechanism for consultation and coordination, and border defence cooperation.

Despite such robust mutual agreements, the deterioration in relations will result from varying subjective interpretations, as it has in the past. In the yet to normalise border stand-off, India has lagged China in containing the flare-up domestically given its political culture and the role of its leadership, which differs from that in China. Analysts in both countries must account for the variation in each other’s political system and devise accurate frameworks to evaluate each other’s strategic intention.

While China defends the ‘fundamental interests’ of its citizens (National Security Law of the People's Republic of China, 2015), the Indian State is committed and held responsible by its Constitution to protect the fundamental rights of its citizens, which are also guaranteed. This difference places the notion of ‘public opinion’, ‘freedom of expression’ and ‘role of media’ in India along with ‘State-citizen relationship’ at odds with that of China. In a situation that requires tact and careful articulation of policy, such as border disputes, the Indian leadership’s power to shape or control public opinion is limited and, in fact, at times, held hostage to it.

For example, just prior to the high-level meeting between the senior military commanders of the Indian Army and the People’s Liberation Army on June 6, the Indian Army had to issue a notice – “At this stage, therefore, any speculative and unsubstantiated reporting about these engagements would not be helpful and the media is advised to refrain from such reporting.”

External observers attempting to decode India’s intentions must therefore view Prime Minister Modi’s Maan Ki Baat or visits to Leh as an act of internal communication to strengthen his constituency and source of his political power, and understand the political context.

The absence of any serious attention to this fundamental problem of strategic communication may lead India on a collision path with China, as it has in the past. Inclusion of variation in politico-strategic culture and associated sociology as factors in the Sino-Indian bilateral relationship will go a long way in reducing misperception with respect to each other’s strategic intention. The central purpose of strategic communication is to reduce uncertainty and not restore it, unless intended otherwise.

(The writer teaches history, politics and culture and is a member of the BRICS Advanced Studies Institute at Sichuan International Studies University, China)