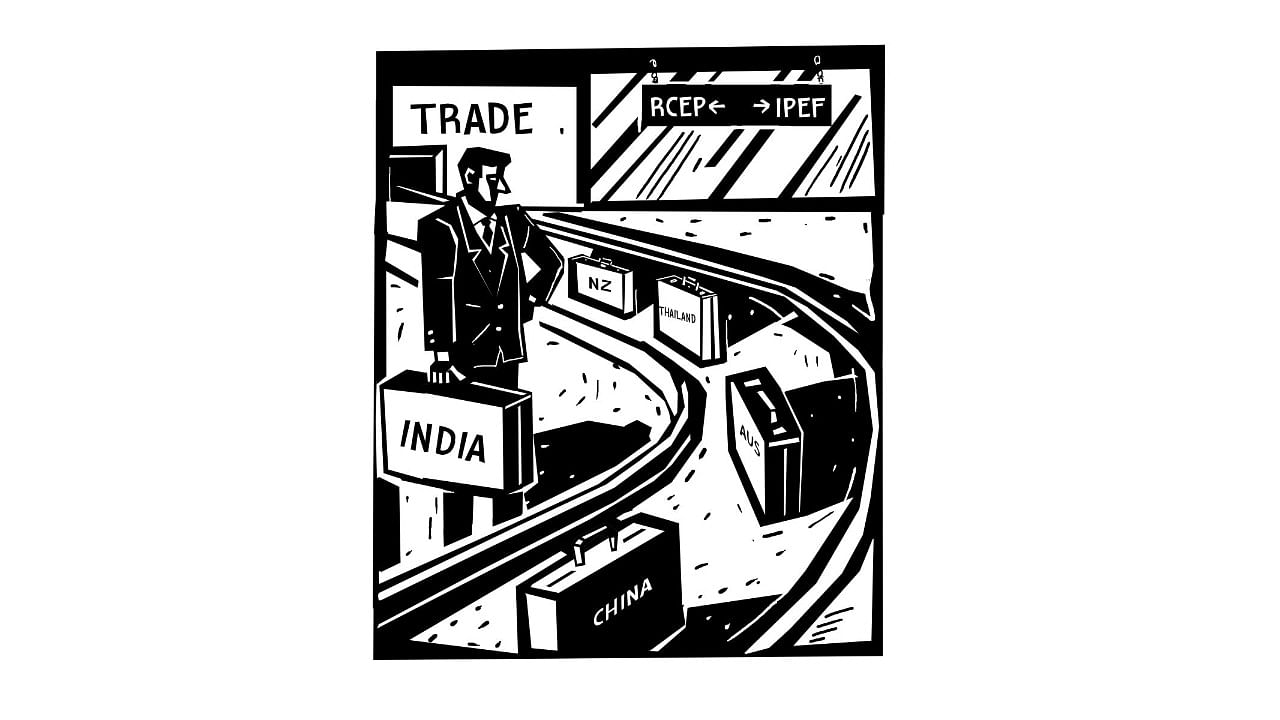

Three years ago, India abruptly walked out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a free trade agreement among 15 nations, including China. The RCEP trade negotiations had been going on for nearly 10 years, during which India had been an active and enthusiastic participant. The present RCEP grouping represents about 30% of global GDP and rising. Intra-RCEP trade without India is worth $2.3 trillion. The RCEP agreement finally came into force on January 1 this year (they were waiting and hoping India would join). This agreement encompasses broad areas of cooperation and seeks to eliminate nearly 90% of all tariffs, making it a sort of economic union.

India’s apprehension and decision not to join was perhaps due to a fear that Chinese goods would enter duty-free into India, swamping the home market. But our trade deficit with China has anyway been growing steadily for the past three years, and even total trade volume has increased, notwithstanding the clash in Ladakh.

India could benefit from the ‘China plus one’ strategy of many global investors, as they seek to set up factories outside China, in other countries like Vietnam, Thailand and India. But by not joining RCEP, India may have dented its chances of attracting investments in various parts of the manufacturing supply chain in sectors like electronics, textiles and automotive. That is because when investors choose to locate their investments, which span a whole value chain, and when the chain has to cross boundaries, they would choose to be inside RCEP territory to enable seamless movement of goods. If India is outside RCEP, it poses a disadvantage for investors in value chains, when the rest of the chain is in RCEP countries. So, by narrowly focusing only on the trade deficit aspect of RCEP, India may have missed the value chain bus. Also, keep in mind, that India already had a free trade agreement in place with 12 out of the RCEP’s 15 countries before its decision to walk out. It has now signed a free trade agreement with Australia, too, the 13th out of the 15 RCEP nations.

There are three big trade groupings in the world that straddle big parts of Asia. Apart from RCEP, the other two are the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). The IPEF, launched in May, includes 14 countries, and CPTPP includes 11 countries. Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Japan and Brunei are members of all three groupings. India is not present in two out of the three. China, of course, is not in IPEF or CPTPP, because these two groupings were brought together explicitly to keep China out.

The CPTPP is a modified version of TPP, which was led by the US when Barack Obama was President. But under Donald Trump, the US withdrew from TPP and kept out of CPTPP, too. It was meant not just to be a trade agreement but to influence and shape the emerging trade rules in the Asian region, and to counter China’s clout. Thus, it has provisions that cover investment rules, labour and environmental standards, greater integration of manufacturing value chains, etc. The CPTPP is ambitious and is now alluring enough for even China to be knocking on its doors. South Korea and the United Kingdom may be seeking entry, too. Note that Japan now has a free trade agreement with the European Union since 2018. That means the EU, too, has a foot in.

The United States is paying a price for staying out of CPTPP (and, of course, the China-dominated RCEP), in terms of lost trade opportunities and decreased geopolitical clout. That explains the aggressive initiative it has taken in the formation of IPEF. This 14-nation grouping represents 28% of global GDP and a substantial trade volume, too. It has four pillars, comprising trade, supply chains, tax and anti-corruption, and clean energy. The IPEF allows members to opt-out of any pillar. Here, too, India displayed some squeamishness, opting to stay out of the trade pillar. India’s trade minister said that since there were issues like labour and environmental standards, digital trade and public procurement involved, around which there was no consensus among IPEF members, India had chosen to opt-out. He also hinted that higher labour standards imposed by countries like the US and Japan could be detrimental to developing countries like India.

That was effectively implying that India would choose to adhere to lower labour protection standards or allow more “dirty” industries with lax environmental standards, to gain a competitive advantage in global trade. But those days are gone. And India has de facto agreed to harmonise labour and environmental standards with the West since it is also pursuing a free trade agreement with the European Union. So, what is the point of staying out of the IPEF’s trade pillar?

Indeed, right after opting out of RCEP, India has aggressively pursued bilateral free trade pacts with Australia, the UK, UAE, Canada and the EU. Why then the hesitation to sign up for regional and multilateral groupings like the IPEF?

India’s growth is critically dependent on being globally competitive in both manufacturing and services. We also have to be committed to the principle of openness in international trade. Our tariffs should be moderate, and we have to desist from frequent and instinctively protective measures to shield our domestic industry from global competition. And with our commitment to employment generation (not just value addition), India can benefit more from global engagement.

The window of opportunity due to ‘China plus one’ will not be open forever. Labour-intensive exports give us our competitive edge, be it in textiles, tourism and agro-processing, or software services at the higher end. It is in our interest to embrace free or nearly-free trade across all sectors. In a world slowing down due to a recession, even if our share of trade goes up from 3% to 4% of global trade, that would be a huge boost for the Indian economy. And that is eminently feasible only if we are less afraid of open and free trade.

(The writer is a noted economist)