Iran is on the boil. Women are up in arms and the uprising is being crushed by the Iranian government, making global headlines that once again point to the brutality brought about by a mix of fundamentalist ideology and political power. But the Iran story is slightly different from the standard tale of clerics seeking subjugation to their religious demands. It was groups of women who supported the Islamic Revolution of 1979, turning away from the westernised influences brought in by the regime of the US-backed Mohammad Shah Reza Pahlavi, who was overthrown as mass protests took over Iran. Those days, skirts were more common than the hijab. In fact, the hijab was banned! And yet, that was a regime that women helped uproot, raging against what was perceived as an un-Islamic, US-influenced modernity that had made Iran a popular destination for celebrities and Heads of State, a high level of women’s participation, and a country with a pumped-up economy.

A lot changed with the Islamic Revolution, but it would not have been easy to take the women in the workforce and daily life and quickly lock them up at homes. So women were everywhere even after the Islamists under Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s then Supreme Leader, took charge. But the headscarf designated for women was back, often with a touch of fashion attached to it. Soon came a law (in April 1983) that made covering heads mandatory even for non-Muslim and foreign women visiting Iran.

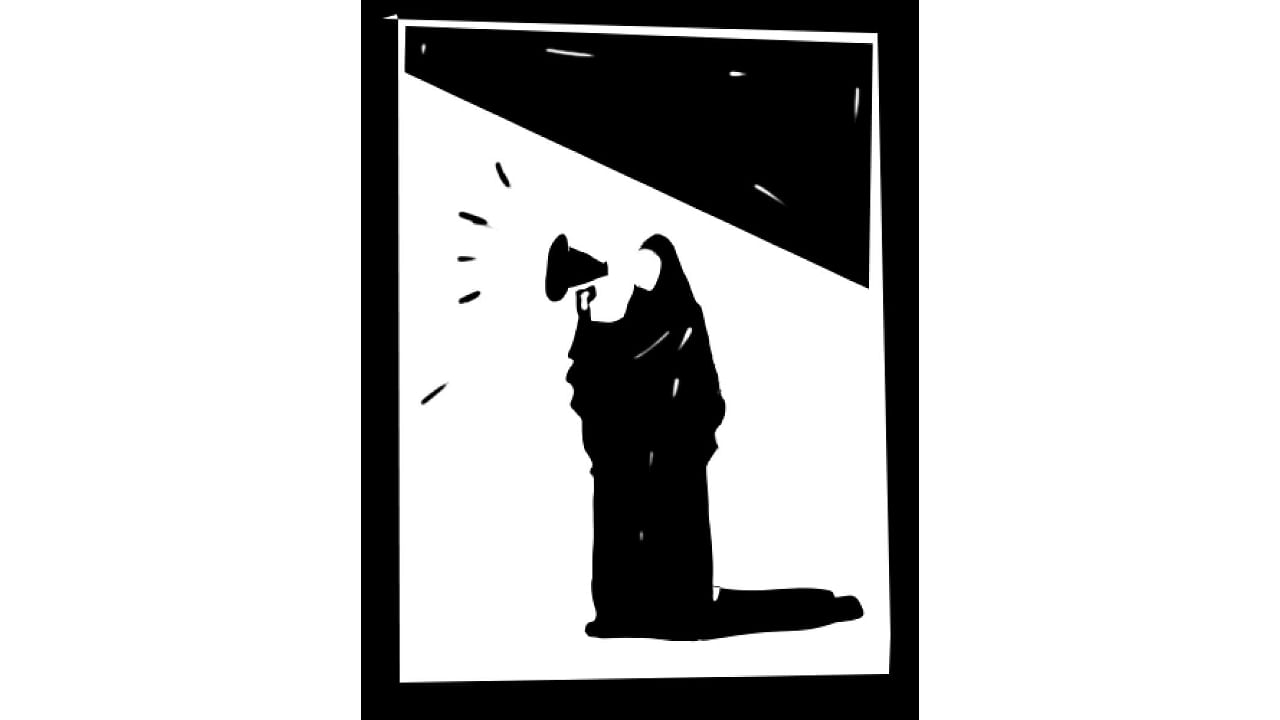

Some two decades ago, this writer was part of a team of Indian lawyers, journalists and social activists invited to visit Iran. An important part of the itinerary was meeting Dr Massoumeh Ebtekar, an immunologist and the then Vice President. As the country turned away from a western-influenced monarchy to an Islamic Republic, Ebtekar had been one of the more famous faces in Iran, both pre- and post- the Islamic Revolution. She had lived for some years in the US with her parents before returning to enrol in an Iranian university. It is here that Ebtekar chose to start wearing the chador and joined the revolution. English-speaking and articulate, she became the voice of the revolution as the spokesperson of a group of militarised students who laid siege to the US embassy in Tehran and held 52 American diplomats hostage for over 444 days, before finally releasing them on January 20, 1981. The “nun”, as she was known to the West for the signature chador covering her from head to foot, Ebtekar went on to become the most powerful woman in the Islamic Republic as one of the four Vice Presidents of Iran.

Ebtekar and members of the government-associated women’s group that initiated our visit spoke of the important role that women played in the economic and socio-political life of Iran. As one of them said to me: “We are everywhere”. That was true then. From the tarmac off Mehrabad International Airport to the malls and offices dotting Tehran’s tree-lined boulevards, women were everywhere. Mostly in black and bustling around, or working behind counters and desks. Though Ebtekar’s twitter feed today has nothing on the current protests by women, she is now seen as a reformist and has often criticised the government, at least on its environmental policies.

In 2012, she and several other women wrote for a book that sought to provide contemporary insights on women in Iran since the 1979 revolution. Titled “Women, Power and Politics in 21st Century Iran”, a review of the volume noted its effort: “Written by women, the majority of whom live and work in the country, this anthology endeavours to counter mainstream western representations of Iranian women as oppressed and subordinated, and instead to depict the modes of resistance and negotiation they have adopted. The editors frame this narrative in terms of the women's struggle against orientalism and imperialism, and against traditional Iranian patriarchy.”

As the review pointed out, a key term was “indigenous”, to describe the post-1979 revolution of women “in contrast to the arguably less authentic movement that had been associated with the Shah's projects of westernisation and modernisation.” Yet, the review authors presciently pointed out: “While we acknowledge the efforts of these women, we should also note that they have been given a voice by the State because they share a common politico-religious frame of reference with it. This tends to undercut the editors’ description of the post-1979 Iranian women’s movement as ‘diverse’; it seems that certain forms of femininity and sexuality have been favoured by the Islamic State at the expense of others.” In essence, a sarkari form of feminism was taking root, while the march continued, slowly but surely, toward more exclusion, segregation and increased tyranny as newer controls on women took shape.

An example of this is Iran’s Parliament, the Islamic Consultative Committee, approving a law segregating healthcare given to men and women. Since there were not enough women doctors, this put 30 million women at risk. While gender segregation has not been so successful beyond schools, where it is enforced, the implementation of the Same Sex Health Care Delivery system (SSHCD), a religion-based separation of women from men in a medical environment brought new ways of enforcing gender separation. In 2012, some university hospitals started gender exclusion policies, dividing the sexes in healthcare treatment and using female physicians only in the care of women.

Newer harsh laws against women since 1979 have pushed women to the back of public transport buses as gender segregation in public was approved. Others destroyed women’s protection under family law, lowered the age of marriage from 18 to 13, and removed women from certain fields of employment and study. Changes in family law articulated male guardianship in a specific way. Under the new regime, this meant that though regarded as financially independent, the wife now required the husband’s permission to leave the house. Today, a man can determine what work is appropriate for his wife and can demand that she leave her job; and men can divorce while retaining custodial rights over children while women are responsible for child-bearing and rearing but lack custodial rights.

The horrible tales of crackdowns on protesters that are emerging from Iran today are testimony to the fact that sarkari feminism has failed and a point of no-return has been reached. Many efforts have been made to shape the narrative on women, but ultimately, what was sought to be sold to the world has not been bought by the ordinary women of Iran.

(The writer is Managing Editor, The Billion Press) (Syndicate: The Billion Press)