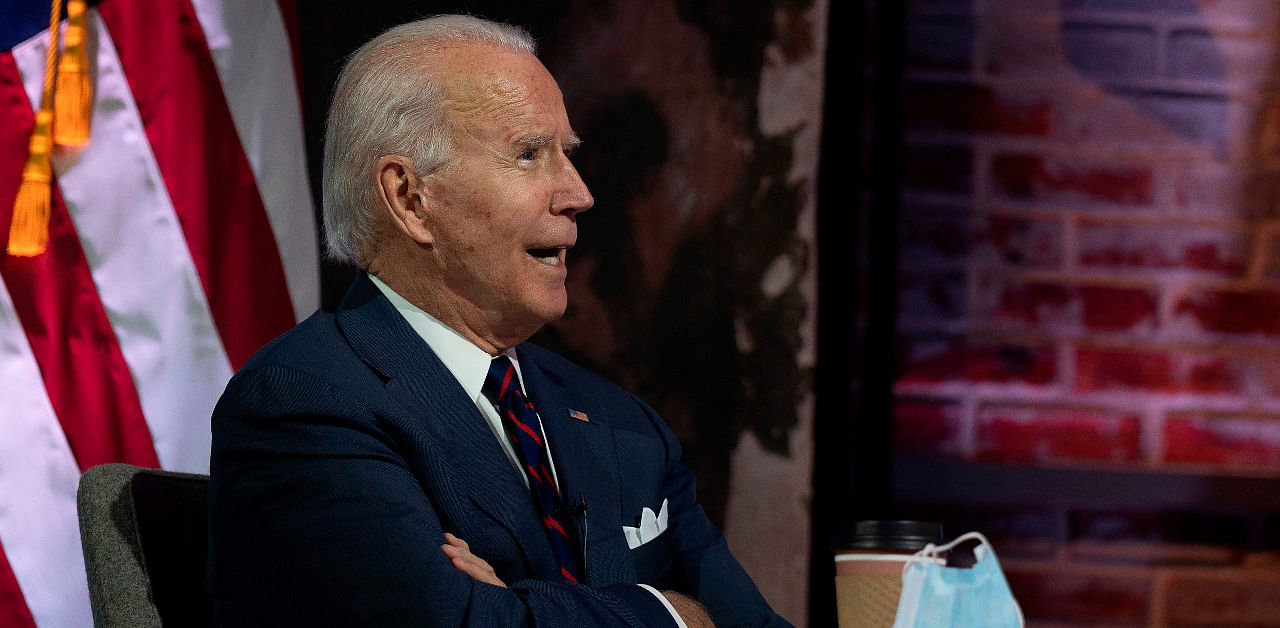

President-elect Joe Biden has promised to move quickly to rejoin the nuclear deal with Iran so long as Iran also comes back into compliance. But that vow is easier said than done.

While Biden’s pledge pleased the deal’s other signatories, who were angry that President Donald Trump withdrew from it two years ago, returning to the way things were maybe impossible, complicated by both Iranian and US politics.

Trump, even as a lame duck, is moving quickly to increase US sanctions against Iran and sell advanced weapons to its regional enemies, policies that would be difficult for a new president to reverse.

Last week, he asked his advisers for options to launch a military strike against Iran but appears to have been talked out of it. His aides argued that an attack could quickly lead to a larger war.

Iran, where President Hassan Rouhani faces strong opposition from conservatives in elections set for June 2021, is expected to demand a high price to return to the deal, including the immediate lifting of the punishing sanctions imposed by the Trump administration and billions of dollars in compensation for them.

Those are demands that Biden is highly unlikely to meet — especially given strong congressional opposition.

Iran has some leverage. When Trump took office, Iran had roughly 102 kilograms, or about 225 pounds, of enriched uranium, whose production was limited by the 2015 agreement. After the United States withdrew, Iran declared it was no longer bound by the agreement and resumed enriching uranium at higher levels.

The International Atomic Energy Agency said last week that Iran now had more than 2,440 kilograms, which is more than eight times the limit set by the 2015 nuclear deal. The “breakout” time for Iran to possibly make a nuclear weapon — an ambition it denies — is now considerably shorter than a year.

During the campaign, Biden called Trump’s decision to abandon the deal “reckless” and said it ended up isolating the United States, not Iran.

“I will offer Tehran a credible path back to diplomacy,” Biden wrote in a September op-ed for CNN. “If Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal, the United States would rejoin the agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiations.”

A week ago, after Biden’s victory, Rouhani welcomed the initiative, calling it “an opportunity” for the United States “to compensate for its previous mistakes and return to the path of adherence to international commitments.”

The choice of the word “compensate” was not accidental, said Robert Einhorn, a nuclear arms-control negotiator now at the Brookings Institution. Iran says it wants Washington to pay for the billions of dollars in economic losses it incurred when Trump pulled the United States out of the Iran deal in 2018 and reinstituted sanctions that it had lifted.

Since then, Trump has piled on more sanctions. This maximum pressure campaign, as the administration has called it, devastated Iran’s economy but failed to push Iran back to the negotiating table or to curtail its involvement in Iraq, Syria or Lebanon.

The administration is also trying to further limit Iran’s support for proxy militias in those countries. It is selling more sophisticated weapons to the Arab monarchies in the Persian Gulf — countries that see Iran as an enemy and have their own regional ambitions — and accelerating the transfer of F-35 fighter jets to the United Arab Emirates.

Some think Trump will take more kinetic measures, including further sabotage and cyberattacks on Iran’s nuclear or missile programs or even military action, which Israel, Egypt and the Gulf allies would most likely support.

“I don’t think the administration is finished on the Iran issue,” said Mark Dubowitz, chief executive of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a long-standing supporter of a tough policy on Iran. “I think people are going to run hard for the next three months against Iran, knowing that after January there could be a very different Iran policy in place.”

Iranian negotiators know that the United States would never provide financial compensation, Einhorn said. “But they may stake out a tough negotiating position, especially given the dynamics of their upcoming election.” He suggested that Iran would demand not just the removal of the nuclear-related sanctions but also those imposed for human rights violations, ballistic missile development and support for terrorist groups, which a Biden administration would find politically and technically difficult to do.

Short of a quick re-entry into the nuclear deal, Einhorn said, the parties should work toward an interim agreement, in which Iran would roll back a meaningful part of its current nuclear buildup in exchange for partial sanctions relief — especially giving Iran access to some of its oil revenues now blocked in overseas bank accounts. Iran might welcome such an interim arrangement if it gave the economy a quick boost, especially before the mid-June elections.

But given the complications of the US transition of power, with the requirements for security clearances and Senate confirmation already slowed by Trump’s refusal to concede defeat and cooperate with Biden, top officials might not be in place very soon. The practical window between inauguration Jan. 20 and June is likely to be only two or three months, which argues for a rapidly constructed “back channel” between Washington and Tehran after Biden takes office.

Despite Trump’s pressure campaign, Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has kept the door open to a US return, refusing to completely abandon the nuclear deal, said Ellie Geranmayeh, an Iran expert with the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Iranians opposed to the initial deal argue that the United States has proved it cannot be trusted, and Iran rejected any negotiations with Trump. But Khamenei provided Rouhani “the green light, the political space to make these messages to a Biden administration” about Iran’s desire for Washington to return to the deal, Geranmayeh said.

At the same time, she noted, Rouhani’s hard-line opponents will not want him “to get this win before the elections in June, and they will look to jam this effort as the Republicans will try to jam Biden’s,” she said. Biden could quickly lift a number of sanctions tied to Iran’s nuclear activities, including approving more waivers allowing Iran to sell oil. He could ease travel restrictions on Iranian citizens, increase humanitarian trade by easing banking impediments, and lift sanctions on some key officials, like Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, the main nuclear negotiator.

But sanctions instituted under the category of counterterrorism and human rights, like those against the Revolutionary Guard, would be harder to void, especially because many Democrats also support them. But Geranmayeh said that Iran would insist that the United States lift the sanction against the Central Bank of Iran, accused of financing designated terrorist groups, so that it can once again use the global banking system.

If the Iran deal can be reconstituted, Iran has said it is open to talks on other issues, especially regional concerns around Iraq and Syria. But Iran has so far refused to put on the table its missile program, which is already under separate US and U.N. sanctions.

Some, like Trita Parsi, of the Quincy Institute in Washington, think Biden should aim higher, for example by proposing normalizing diplomatic relations with Iran. “Putting the puzzle of US-Iranian diplomacy back together will be tremendously difficult,” he wrote in Foreign Affairs. “But the last few years have shown that not trying will not make the difficulties go away.”

The key, as with all major policies in Iran, is Khamenei, now 81. He regards the US as a doomed country in “political, civil and moral decline.” He went along with the nuclear deal because it promised significant economic benefits from the lifting of sanctions and now apparently regards his scepticism about the United States as confirmed by Trump’s withdrawal from the pact.

But with the change in US leadership, he again sees the possibility of easing the economic straitjacket that renewed US sanctions have imposed.

“Despite Khamenei’s hubris, a Biden presidency presents both an opportunity and a challenge for Tehran,” Karim Sadjadpour of the Carnegie Endowment wrote. “The opportunity is a chance to improve the country’s moribund economy; the challenge is that Tehran will no longer be able to effectively use President Donald Trump as a pretext or distraction for its domestic repression, economic failures and regional aggression.”