The farmers' movement captured the national imagination in 2022-21 and continues to do so. The farm unions inscribed their discourse and analysis reflecting upon rural society, politics and policymaking programmes related to rural India. Thus, farmer unions' politics, history, and ideological differences also deserve our attention.

The recent mobilisation was not unprecedented. Cutting across boundaries of religion, region, caste, and language and uniting them into one identity of kisani, such alliances have been formed before. Leaders such as Ajmer Singh Lakhowal of Punjab, M D Nanjundaswamy of Karnataka and others came together with Mahendra Singh Tikait of Uttar Pradesh against the despotism of neoliberal policies in agriculture.

Mahendra Singh Tikait's Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU) was the flagbearer of protest against the World Trade Organisation (WTO)/GATT (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) in the 1990s. It galvanised the support of other farm unions. There were many state-level BKUs, but the top leadership and authority remained with Mahendra Singh Tikait, known by his honorific Baba Tikait, since he had traditional roots and enjoyed the support of khaps (clan organisations).

The BKU has faced numerous internal organisational strife - several factions of the BKU have come into existence from time to time. The BKU faced an organisational revolt first in 1998 when Rishipal Ambavata, a Gujjar farmer leader from Haryana, left the outfit and formed the BKU (Ambavata). Rishipal was the national president of the BKU's youth wing and a respected leader.

Another setback was in 2008, when, in its Haridwar Mahapanchayat, V M Singh left the BKU and formed the Rashtriya Kisan Mazdoor Sangathan. It was widely believed that the reason behind this was a fight over the 'pagri' of the BKU. A section of the BKU wanted him to become president of the organisation, which triggered friction at the Haridwar conference of the BKU. Later, V M Singh distanced himself from the organisation, which led to the BKU losing its leader in the terai region of Uttar Pradesh.

The BKU's protest against the rape of a Muslim girl, Naima, in 1988 and against the Meerut riots that halted the spread of violence in the villages strengthened the BKU's secular image, but 2013's Muzaffarnagar riots missed the presence of Baba Tikait as he had passed away the previous year. Back then, the BKU's national vice president was Gulam Mohammad Jaula, a contemporary of Baba Tikait and his close aide. He left the BKU because of its alleged participation in the riots and formed the Rashtriya Kisan Mazdoor Manch. Mahendra Singh Tikait invoked slogans like Allahu Akbar and Har Har Mahadev together through the platforms of the BKU. He also included many Muslim farm leaders in its local and national leaderships.

Another farm union considered close to the Bhartiya Janta Party is the BKU (Bhanu), a faction of the BKU (Tikait). The organisation's primary support comes from the middle part of western Uttar Pradesh (Braj region) and lower Doab and primarily among the Thakurs of the area. Bhanu Pratap was part of the BKU (Tikait) till 2013. He was the union's state president when he left Tikait and formed his union over 'differences'. He played an important role in counter mobilisations against the farmers' protests of 2020-21 due to his union's favourable equation with the ruling government.

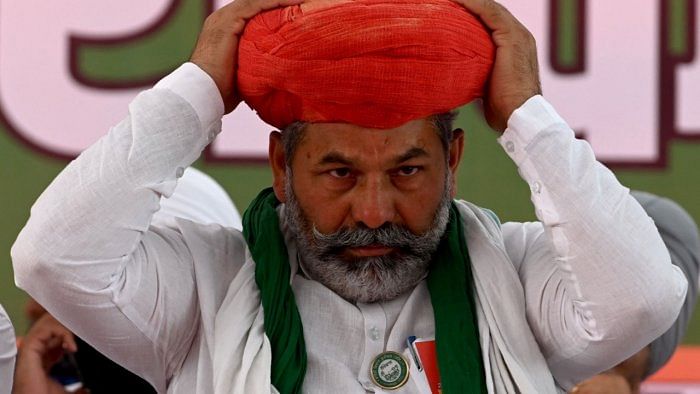

The BKU (Tikait) lost vital constituencies of different agrarian castes because of these splits. The BKU (Tikait) always claimed to be non-political. Still, in 2004, Mahendra Singh Tikait's son Rakesh Tikait formed the Bahujan Kisan Dal and contested some seats but could not win any. All these attempts to politicise farmers and agricultural labourers as one working class through unique typologies of Bahujan and Kisan were unique, at least in the sphere of the farmers' movement.

Recently, a faction of farmer leaders broke their ties with the BKU (Tikait) and accused the Tikait brothers of indulging in 'active politics', defying the apolitical tradition of the BKU. These leaders, namely Rajesh Chouhan, Dharmendra Malik, and Harinam Singh Verma, have formed a new union called BKU (Arajnaitik), or BKU apolitical.

However, the logic behind this is fallacious. Even in the past, the Tikait family has been associated with active politics and even contested elections, but these leaders did not object then. Interestingly, the head of the Gathwala Malik Khap, Rajendra Malik, is the adviser of the BKU (Arajnaitik). There was an attempt by the ruling party to divide khaps and delegitimise the farmers' protest, which Rajendra Malik had supported.

When the BKU (Tikait) organised a massive rally in September, he refused to join it. Rajendra Malik instead went on to join the rally of the Hind Mazdoor Kisan Samiti, the organisation which supported farm laws. BKU(Tikait) media head Dharmendra Malik also developed a sorrowful relationship with the Tikait brothers. They ostensibly ensured he should not get a ticket for the Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections in 2022.

One also has to look at the role of castes while analysing the faction politics of the farm unions. Caste mobilisations within BKU (Tikait) have different implications now with the formation of this new faction instead of one where other non-Jat leaders of the organisation faced a sense of disregard. Such problems can be effectively dealt with when there is an equipoise of resources and positions, unlike BKU (Tikait), which revolves on the axis of one family.

However, the BKU(Tikait) has acquired robust ground for reclaiming its glorious history after the farmers' protest of 2020-21. This has provided the BKU (Tikait) with the much-deserved boost to instil credibility among its supporters. Tikait family has used it to revive its legacy.

There are two fundamental paradoxes visible due to the upsurge of the farmers' movement in India. The first is the failure of farmer organisations to address their problems correctly. The second paradox is the practice of caste mobilisation creating hostilities between inter-caste relations and giving a free hand to politicians who exploit caste divisions, and this newly formed outfit also contributes to this. The fact remains that politicians do not want farmer organisations to strengthen their pillars irrespective of the political party they might be affiliated with.

The political dynamics of caste have changed nowadays. The mere support of a particular caste to a farmers' organisation is no longer helpful. Instead, inter-elite and intra-elite caste-based competition is at the centre of politics. The caste-based rivalry eventually leads to competition between various families, which vie to share power among the castes. And the ruling party, on the receiving end, has greater chances of benefitting from power struggles between elites of different castes because many castes are directly and indirectly aligned with the ruling party. Hence, the political party ultimately sets the rules for farmer organisations upon which the social and political agenda are being played. This newly formed union could be prone to fall into such a trap.

(Shivam Mogha and Harinder Happy are research scholars at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.