I’m not usually given to bursting into tears in public, but Saturday, Jan. 16, was an exception.

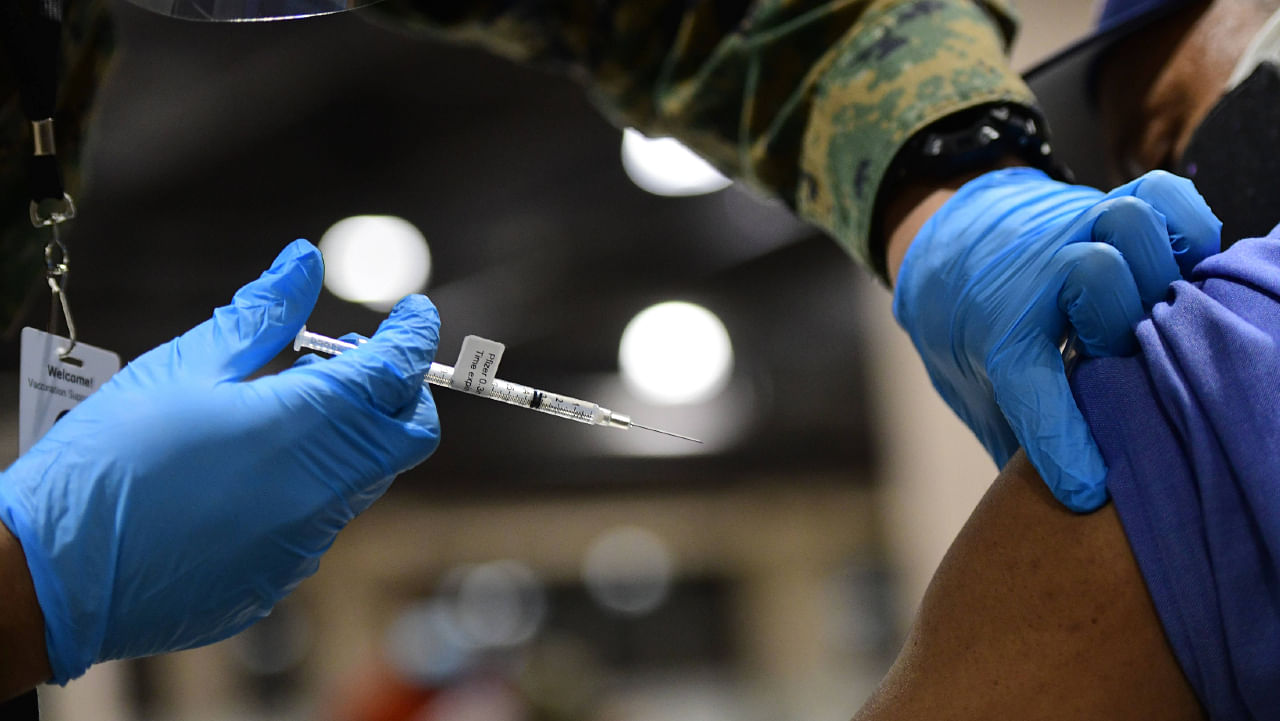

I was getting my Covid-19 vaccination in Queens when it happened.

A friendly physician, who identified herself only as Dr. Burke, approached me to make sure I was OK. I told her I was just overwhelmed with emotion. “It’s OK,” she said. “A lot of people are crying here today.”

I’ve spent most of my 50 years in journalism as a war correspondent; when the pandemic hit, I couldn’t help but see the coronavirus pandemic in familiar terms. Countries around the world were transformed into battlefields.

Like most of us, I have known people who have died of the virus. <a href="https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/26/opinion/war-correspondent-covid.html" rel="nofollow">This has made the pandemic very different from other wars I’ve covered,</a> which is nearly all of them since Cambodia in 1979. In other wars I had an out: I could always leave and go back home.

That, of course, isn’t an option in a pandemic; the front lines in the fight against the virus are everywhere, and we are nearly all on them.

With no home leave, so to speak, I felt bereft of home in a way more profound than during any field assignment I had been on before. As someone who has spent most of his career on farther shores, I have found this past year particularly hard to bear. I was abroad at home, and never had I felt so isolated and alone.

My litany of collateral damages will sound familiar: the weeks of quarantines, the unattended weddings and funerals, the skipped Labor Day family barbecue. And forget about graduations and plain old birthday parties; I haven’t seen my three children, all of whom live in Europe, for most of a year. Thanksgiving, normally an affair for 30 or 40 extended family members, was off limits.

I found our canceled Christmas to be particularly wrenching. Our family event, hosted by my sister Darlene, typically boasts 50 place settings. This year I was not invited, of course; I was heartbroken over that till I quickly realized that if I had been called upon to attend, I could not have gone. Outside of her immediate household of six family members, most of us dialed in by Zoom or FaceTime. That way we all stayed safe, if a bit sad.

Also Read | A coronavirus variant by any other name … please

It was a touching scene to see the devoted and unpaid volunteers running the vaccination site (normally the bustling, 2,000-student Aviation High School) where I had booked my first dose. The volunteers were wearing Day-Glo green or orange vests with bibs that read, “I speak Spanish,” “I speak Chinese,” “I speak Cantonese” or “I speak Urdu.”

The lists of languages went on and on; after all, we were in Queens, as polyglot a place as you’ll find in New York City. This virus has known no boundary, it has left no community untouched. The volunteers were determinedly efficient: From arrival to the shot in my arm, maybe 15 minutes elapsed.

I was one of the first<a href="https://www.nbcnews.com/science/science-news/supply-shortages-registration-issues-nyc-struggles-vaccine-distribution-n1254446" rel="nofollow"> </a>New Yorkers vaccinated as the list of those eligible expanded to everyone over 65 and anyone who is a vulnerable person or is taking care of someone who is. The city was handing out shots so quickly that Mayor Bill DeBlasio warned that it was in danger of exhausting its first batch of vaccine doses.

“It’s been so exciting,” my vaccinator, Denise Mahon, told me. “The first day it was like a carnival atmosphere here. People were so happy.”

“The scientific achievement has just been amazing,” Dr. Burke said.

Ms. Mahon is normally a school nurse, tending to students, not vaccinating baby boomers, the vulnerable and the elderly for 13 hours a day.

After getting jabbed, I was moved along to a holding area, in normal times the school cafeteria, to spend 15 minutes making sure there was no allergic reaction or other problem. Very few people had complaints. While waiting, my girlfriend visited the New York State Department of Health website to book my second dose. She found an opening on Valentine’s Day. V-Day. It felt auspicious, to finally have a holiday that gave us something we really could celebrate. I knew I’d be dreaming of spending Christmas with my children and my extended family at my sister’s soon again.

When Valentine’s Day came, I went in for my second dose and felt nearly overcome with relief, though this time dry-eyed. Also getting her second dose that day was a New York City schoolteacher named Yesenia Garcia, 49, from Jackson Heights, one of the Queens neighborhoods hard hit by the pandemic. Her vaccine “was like getting a kiss for Valentine’s Day on my arm,” she told me.

Early in the pandemic, Ms. Garcia, who teaches — now mostly remotely — English as a second language, saw friends and colleagues lose their lives to Covid-19 as the city delayed closing the schools. Now, she said, she is especially relieved that she can see her parents, both in their 80s, without worrying about putting their lives at risk.

“I was so grateful to science when the vaccine arrived, ” Ms. Garcia said. “This all proves that science really has to be celebrated and protected from power-hungry people like our last president and others who want to twist it and use it to their own advantage.”

Walking away fully vaccinated felt like a small but memorable victory in this home-based war, a V-Day for which I was not only reporter, but protagonist.