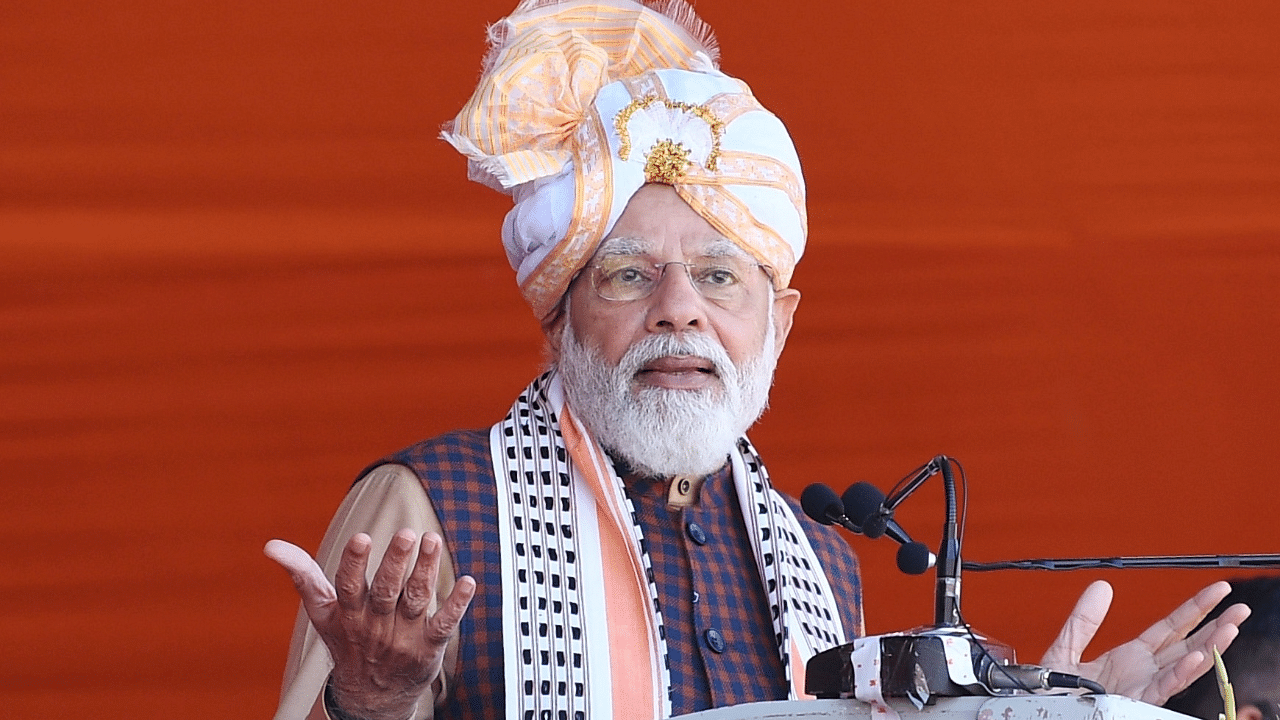

In the seven-and-a-half years that he has been Prime Minister, Narendra Modi has not answered any questions, has not made the customary statement in Lok Sabha after a State visit abroad, has not engaged in a tete-a-tete with a fellow member during a debate. The only time he took part in the proceedings was during his first year in office. When there was a strong protest from Opposition members over a controversial remark by Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti in an election rally, where she posed a choice between “Ram’s sons” and “illegitimate sons”. She apologised, but the members demanded an explanation from the Prime Minister.

Modi, speaking in the Lok Sabha and in Rajya Sabha in December 2014, asked Opposition members to consider the fact that she was from a village and asked them to be magnanimous and accept the apology.

The only time that Modi has spoken through these seven years in Parliament is during the reply to the Motion of Thanks to the President’s Address. And he takes care to mention some of the members who spoke in the debate. In February 2017, in his reply, he retorted to former PM Manmohan Singh’s criticism of demonetisation as “organised loot” and “legalised plunder” saying that despite the scams surrounding him, Singh’s image remained clean but that was because he (Singh) knew the art of “bathing with a raincoat on”.

Before every session, Modi has given a soundbite to the media expressing hope that there would be useful discussions in the two Houses, but he has never been an active participant in any discussion in Parliament. This is quite in contrast to the sentiments he expressed about Parliament when he was elected in 2014. He genuflected on the steps of Parliament House and described it as the “temple of democracy”.

As a Member of Parliament from Varanasi, Modi has paid a lot of attention to the constituency he has been elected from, visiting the place regularly, even taking former Japanese PM Shinzo Abe there in December 2015, and then there is the corridor he has got constructed from the riverfront to the Vishwanath temple. He seems to believe that as an MP from Varanasi and as PM, it is enough if he beautifies the place. He is doing his duty by his constituency. Would his constituents also like to see him participate in parliamentary proceedings?

There is a larger implication of Modi’s absence, or silence, on the working of Parliament. It seems that that the Modi government in Parliament is managed entirely by ministers. It is indeed the case that it is the ministers of various portfolios who answer the questions, but the occasional intervention of the PM as leader of the Lok Sabha would have given the Modi government a better image.

Modi may believe that his image lies in the work of the government and not in his intervention in Parliament, but that would be wrong in a parliamentary democracy. The PM needs to defend his government in the two Houses. He should be heard in Parliament, rather than at public rallies.

In the British House of Commons, every Wednesday is the ‘Questions to the Prime Minister’ or ‘Prime Minister’s Question Time’, and the PM has to answer directly the questions of the Leader of Opposition. In the Indian Parliament, however, while this tradition exists, the PM can have the Minister of State in the PMO answer. And that’s what has happened so far in the Modi regime.

This seems to be a personality trait. He does not like to be questioned. And it seems to be also the reason why he has not held a single press conference in these seven years. The interviews he did as Chief Minister of Gujarat did not show him to enjoy the questioning. And the few interviews he did after he became PM were from those who were more inclined to praise him rather than to question him and his government. Even former American President Donald Trump, who hated the media and publicly said so, nonetheless faced the media day in and day out, and he did it in his own bumptious way. But Modi avoids being confronted with questions, whether in Parliament or with the media.

The effect of a disengaged Prime Minister in Parliament is that the Opposition is restless and dissatisfied. A PM who addressed them directly could alter the tenor of the proceedings in the two Houses. Modi sits through the presentation of the Budget, but he does not do so on other occasions. If he is present in the House, and if he were to answer a question or two in the form of clarification or a statement, then the Opposition would be satisfied. It is true that the Opposition may use the opportunity of the Prime Minister’s presence to insist that he respond. But this is indeed the spirit of parliamentary democracy. The Prime Minister is a member of the House, and as head of the government, he should be interacting with the legislature.

When Modi came into office, observers like Arun Shourie predicted that Modi’s would be a presidential style of governance, that he would take decisions on his own and that he was not merely the first among equals in the Union Cabinet. It seems that Modi has adopted the same presidential attitude towards the legislature, too. He remains aloof from Parliament. It will be argued that each Prime Minister brings his own style to the office, and that Modi’s aloofness is his style and that one should not complain about that. We need not quarrel with Modi’s political stylistics. But it remains incumbent on us to observe and describe the phenomenon.

(The writer is a New Delhi-based political commentator)

Watch the latest DH Videos here: