Sanjeev Sanyal, the principal economic adviser, recently said, "Many of these old master plans, Le Corbusier-inspired planning and ideas that we still teach by the way in the SPA (School of Planning and Architecture) and other institutions, first of all, we need to throw them in the dustbin."

He meant that basic Nehruvian principles of planning a city must be dumped, and we should adopt more market-friendly city developmental models of planning. During our interaction in an urban age conference held by the Deutsche Bank and the LSE in November 2014, Sanyal was rabidly intolerant towards state intervention in the planning processes.

What we experience post-2014 since Narendra Modi took over and announced his strong antipathy towards any state intervention, cities being foremost amongst them, many fancy ideas for attracting private capital investment were announced. These were quite in tune with what Sanyal has said.

One hundred smart cities were supposed to be the lighthouses of urban growth and SPV (Special Purpose Vehicles) as the new governance models for quick and rapid development. The private capital was supposed to enter these smart cities for infrastructure development projects and ameliorate the problems of the people. However, as a practitioner and an urbanist, I can say this with full affirmation that it's been a complete disaster in city development.

Also Read | Why illegal layouts thrive

Neither the private capital entered these cities nor the SPVs could bring in a pro-people governance model. The SPV model was synonymous with writing an obituary of the 74th constitutional amendment, thus reducing it to a mere bureaucratic riddle.

To get rid of Corbusier's model, the central government wrote the National Urban Policy Framework (NUPF) document, which was full of contradictions. Sanyal was instrumental in authoring this document. The document was so controversial that it had an ignominious exit. Even the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Development has not owned this document. The NUPF, with ten sutras, was supposed to provide the vision for city development for the coming few decades in the country. It was supposed to be like the first urban commission set up by the Rajiv Gandhi government, which architect Charles Correa had headed.

The aversion to the planning institutions by the BJP and its cohorts and advisers like Sanyal is quite natural. The basic principle of development is, "Let the market determine the development trajectory of cities." This is quite the opposite of what was discussed in the UN-Habitat III. Not that the free-market economy principles have not been tested. Since 1990, the urban reforms have been based on such principles. But, post-2008, there has been strong criticism across the globe of how city development is happening.

John Closs, the then executive director of the UN-Habitat, reminded in Quito, the venue of Habitat III, that to ensure the success of SDGs (sustainable development goals), we must go back to the basics of planning. He backed ridding of the decades-old practised model of laissez-faire. It meant that the free-market economy would not alleviate the basic challenges of mass poverty, inequality, unemployment, infrastructure and climate change in contemporary times. Hence, more focus must be given to planning with a people-centric vision.

Sanyal is saying just the opposite. In the guise of failures of successive planning models, he is trying to inverse the entire argument. The failure of planning, globally and in the Indian context, must also be understood in the same framework.

In the Indian context, the state's role in planning was minimised, and market-oriented principles were followed. That is why the city planning institutions in the country are not subject to political control of the city's elected institutions. Nowhere in the country does the city and its citizens and residents plan for themselves.

The city planning is done at the behest of parastatals, which consultants then guide, most of whom come from large consulting firms. These parastatals like the Delhi Development Authority, the Mumbai Development Authority, and the Greater Mohali Development Authority are not answerable to the elected regional or city institutions. Hence, most of the planning is done in contravention of the provisions of the 74th constitutional amendment. The Twelfth Schedule of the Constitution firmly listed that city planning must be under the domain of the city administration.

Post-independence adopting Nehruvian principles, the city development plans emphatically spoke about the issues of the poor and housing. Though the exercise was not ideal or completely inclusive, it still had an element of inclusion. However, post the 90s and now post 2014, there has been a complete absence of these principles after Modi's era. Take, for example, the latest master plan of Delhi - 2041. It mentions that nearly 34 lakh dwellings will be required. But how will this happen? What would be the role of the agencies? All of it is pretty ambiguous. In effect, it intends to play with the land pooling policy and usurp the village commons of the people and thus cater to affluent sections in society.

Sanyal lamenting about infrastructure is correct, but he does not mention that the state agencies must lay the basic infrastructure and not expect the private capital to invest in that area. If it does, then there is a considerable cost which the people have to bear. All that is being done and further consolidated is the massive drive for capital intensive technologies to solve basic problems like solid waste management and even mobility in the town.

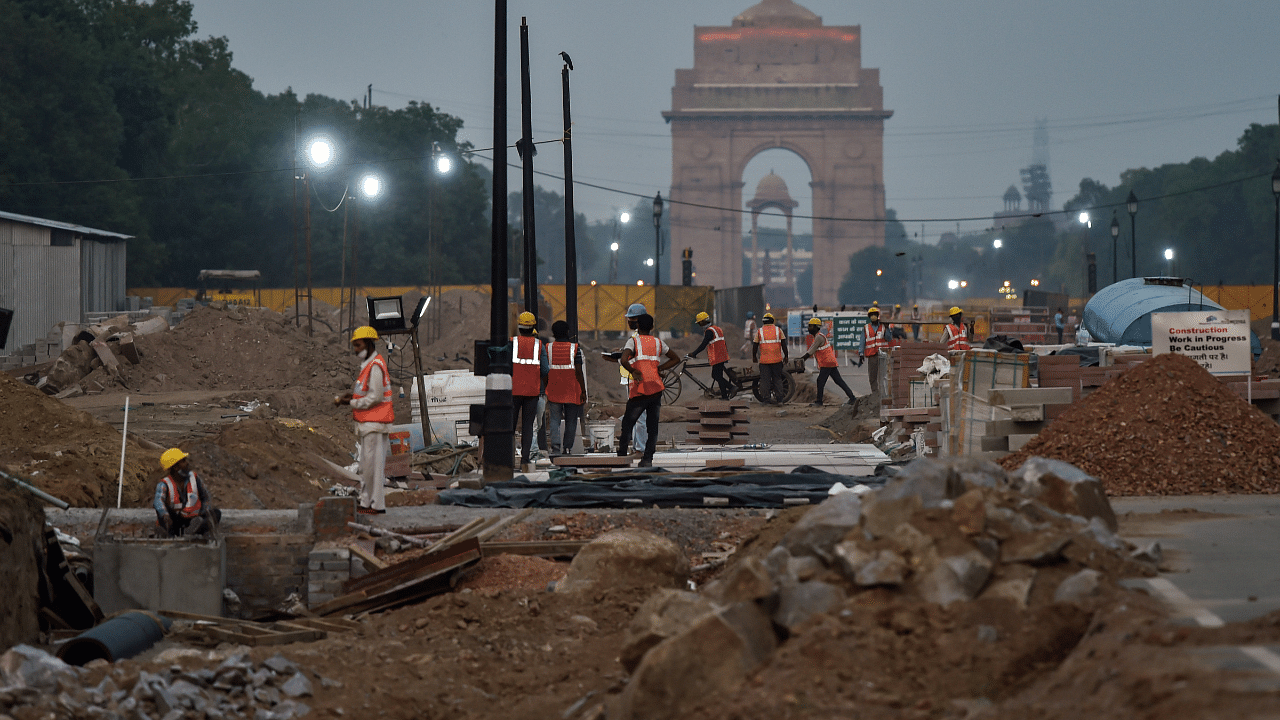

The drive is such that instead of a playground, there is a drive for constructing a stadium. Instead of a primary health centre for a multi-speciality hospital. Instead of decentralised waste management for high capital cost waste to energy plants. Instead of pedestrianised and non-motorised mobility, more flyovers and more capital-intensive technological metros.

While this will not be sustainable, it has confused Sanyal's nonchalance with Nehruvian principles. The same recipe of a free-market economy, a time-tested failure, is being served in the name of putting forth something new.

It is time to allow the blooming of people-centric ideas—cities for people and not vice-versa.

(The writer is a former deputy mayor of Shimla)