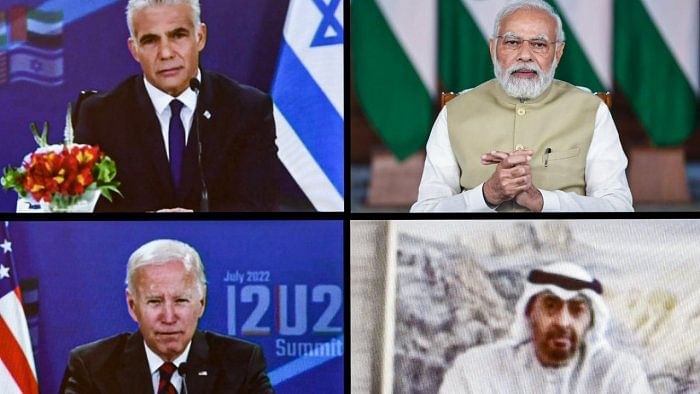

Narendra Modi addresses I2U2 virtual Summit in New Delhi.

Credit: PTI Photo

India’s foreign policy has become uniquely India-centric like never before. India is non-aligned with Australia and the United States of America within the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, popularly known as Quad. It is more in alignment with the fourth Quad member, Japan.

India is equally non-aligned among Brazil, Russia, China, and South Africa, which hitherto collectively constituted BRICS, to be expanded on January 1 adding six more countries. In terms of realpolitik, India has already become non-aligned to the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) with Prime Minister Narendra Modi skipping two successive NAM summits — in 2019 in Azerbaijan, and in 2016 in Venezuela. Amidst the campaign build-up for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, it is highly likely that Modi will skip the next NAM summit in Uganda as well. This month, India virtually non-aligned with the Group of 77, the largest bloc of developing countries in the United Nations when it decided not to send a Union minister to the G77 summit in Havana. In fact, the Modi government dislikes the words ‘developing countries’. It prefers ‘Global South’.

Instead, India is taking the initiative to create new groups — often plurilateral, instead of the huge jamboree that NAM and the G77 have become. One such recent example is the I2U2, which expands as ‘India, Israel, the US and the United Arab Emirates’. The fruits of I2U2’s labours have so far come solely to India in terms of two mega projects that are well in the pipeline.

Another example is the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), which India founded at the recent Group of Twenty (G20) Summit in New Delhi along with six other countries, that lie along the corridor plus the European Union. India took this initiative after having repeatedly tried and failed in threesome tracks to use Indian industrial and commercial assets and the Gulf’s financial resources to tap African markets. The jury is out on whether this plurilateral effort will work, where India’s resources have been largely wasted in unilateral development initiatives and commercial drives in Africa. The nascent corridor is expected to especially focus on Europe’s potentially lucrative connections with the Maghreb. For two centuries, African Maghreb has been in Europe’s sphere of influence.

Simultaneously, at levels lower than those of heads of state and government, India has co-founded this year, the International Biofuel Alliance, and launched its ambitious National Green Hydrogen Mission.

Since fresh life was infused into Quad during its virtual summit in March 2021, India has struggled — with some support from Japan — to keep the four-nation group focused on issues for the common good: tackling the Covid-19 pandemic and vaccines, the climate crisis, science and technology co-operation, and combating cyber threats. The US and Australia are quietly frustrated that India is not prepared to go along in converting Quad into an alliance against the twin Anglo-Saxon nations’ adversaries.

In part, these frustrations played a part in creation of the Australia-United Kingdom-US (AUKUS) partnership nine days before the first in-person Quad summit in Washington in September 2021. Then Foreign Secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla made the Indian position unambiguous. “Let me make it clear that the Quad and the AUKUS are not groupings of a similar nature. The Quad is a plurilateral grouping that has a shared vision of their attributes and values. On the other hand, the AUKUS is a security alliance between three countries. We are not party to this alliance.”

On BRICS, New Delhi’s position is more nuanced. It became clear during the organisation’s Johannesburg Summit in August that the US-dominated unipolar world order is changing and that BRICS is the harbinger of such change. Why else would 60 countries want to be associated with BRICS in some form or other if they cannot become members? BRICS favours de-dollarisation of global finance. India is non-aligned on fast-tracking changes that the more powerful BRICS countries, Russia and China, are pushing for. India is non-aligned within BRICS just as it is within Quad. Russia’s normally plain-speaking Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov sugar-coated these differences in Johannesburg, describing those only as “lively discussions.”

The Modi-S Jaishankar doctrine behind these diplomatic initiatives is similar, but only in scope and challenges to what India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru initiated in the early years of Independence. They are fraught with risks but could externalise the aspirations of the Indian people if they succeed. It is an irony that while India has reduced its non-aligned role as a NAM member, non-alignment in a different avatar is still the guiding principle of Indian foreign policy.

(KP Nayar has extensively covered West Asia and reported from Washington as a foreign correspondent for 15 years)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.