On May 9, 2020, Hu Xijin, editor of Global Times, the mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, published an article prodding his country to expand its nuclear arsenal “in a relatively short time span” to 1,000 nuclear warheads and “at least” 100 DF-41 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Current Chinese nuclear holdings stand at 290 warheads, as per the 2019 edition of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. China’s ‘White paper on National Defence’, released last year, reiterated that the country keeps “its nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required for national security.” Since 1964, China’s nuclear deterrence has rested on the idea of sufficiency to inflict unacceptable damage.

So, should the call for a radical expansion of nuclear numbers by an individual merit attention? Expectedly, the Chinese spokesperson has described it as just one view that highlights freedom of speech in his country. But, the expression of a diversity of views on nuclear issues is not a hallmark of China. In fact, the country cleverly manipulates opacity, deception and ambiguity as part of its deterrence strategy. So, is something playing out here? After all, Xijin is a known hard-line nationalist and has been editor for over 10 years of the Chinese and English editions of Global Times.

China has also been in the process of expansive strategic modernisation -- induction of multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVed) missiles, hypersonic delivery systems, long-range submarine-launched ballistic missiles on a new class of SSBNs, enhanced space-based ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance), navigation and communication, etc. In this process, an increase in the warhead numbers has never figured. Rather, by not adding to its arsenal, China has actually belied American stockpile forecasts. So, why did Global Times, a medium that has been used in the past to launch trial balloons to gauge opinion, publish this piece now? Some decoding may be prudent.

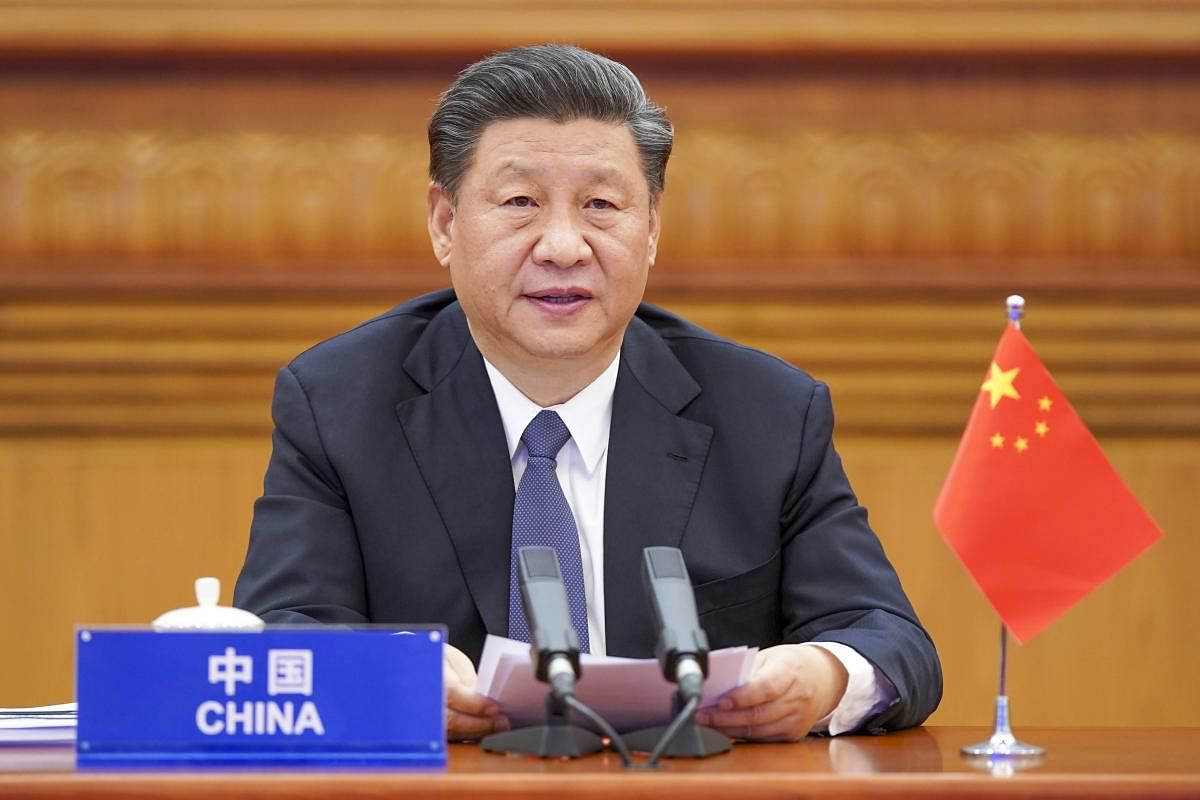

The first purpose of the article could simply be to signal deterrence. At a time when China is under significant pressure from many countries on its role in the raging pandemic, it may be drawing attention to its nuclear capability to deter the possibility of military action in its areas of concern, such as the South China Sea. Interestingly, a ‘leaked’ report of China’s Ministry of State Security to President Xi Jinping was recently cited by the media for emphasizing a high anti-China sentiment which could lead to an armed confrontation with the US. In such an environment, a call to expand the nuclear arsenal could be muscle-flexing of potential capabilities. Undoubtedly, China has the financial capacity and fissile material stockpile to accelerate warhead production, if it so decides. And, Xijin argues for it pointing to US “strategic ambitions and bullying impulse against China”.

Secondly, the article may be building a narrative on a decision that has already been taken to increase the nuclear arsenal. Some surge in China’s nuclear numbers is inevitable given that it now deploys MIRVs on its ICBMs. Depending on how many warheads each missile carries, varying from three to 10, there will be the need for additional warheads. But the requirement may go beyond this in case China thinks it necessary to prepare a bargaining position for nuclear arms control negotiations that it may be obliged to join in the future. China has traditionally been dismissive of such demands on the grounds that its arsenal compares poorly in size with that of the US and Russia. It may now be resizing itself to present an even match.

Thirdly, China may be delivering a message that it is not scared of joining an arms race. President Trump has often expressed that he would pull Russia and China into nuclear overspending and debilitate them. China may be showing its own readiness to pick up the gauntlet. In fact, ironically, given the ravaging effect of Covid-19 on most economies, China may find itself in a better position than others to support ambitious military spending.

Lastly, the nuclear expansion recommendation may reflect the growing influence of contemporary Western nuclear thinking that advocates nuclear war-fighting on Chinese opinion-makers. Xijin writes, “If the US initiates a nuclear war with China, it must not have any chance of winning -- that’s the kind of nuclear deterrent China must secure.” Customarily, China’s nuclear strategy has not associated the term ‘winning’ with nuclear war. But, with the US Nuclear Posture Review of 2018 recommending that Washington should build capability to fight limited nuclear wars with low-yield weapons against military targets, China may be succumbing to the same temptation.

It is to be expected that any move by China, or even expression of intention, to expand its nuclear arsenal would evoke concern in India. An expanding number gap would be perceived as placing India at a disadvantage. Such thinking, however, would be missing the basic fact that numbers in the nuclear game do not matter beyond a point. In fact, China has traditionally believed in the same dictum. Xijin’s advocacy of nuclear expansion is overlooking the point that nuclear deterrence best rests on the idea of punishment and assuredness of retaliation. Chinese and Indian nuclear thought has long been rooted in this wisdom and supported credible minimum deterrence.

Nuclear weapons, by their nature, ensure mass destruction and hence even a few suffice to inflict damage that no rational State could find acceptable or even manageable. There should be no requirement for India to follow suit or enter into a competition of nuclear bean-counting, a wasteful enterprise. Given the blow by the coronavirus to the economy, it will be imperative to rationalise spending in the coming years. Of the defence allocations that it can afford, India would be well advised to focus on nuclear forces survivability than on number additions.

(The writer is Distinguished Fellow, Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi)