When Seth Shostak, an astronomer who scans the cosmos for signs of extraterrestrial intelligence, asks middle school students how many of them want to go to Mars, all hands shoot up. When he asks how many would rather design robots that go to Mars, most hands drop back to their desks.

And when he asks general audiences how many would go to Mars even if it meant dying a few weeks after arriving, he invariably finds volunteers in the crowd. “People are willing to risk everything just to see Mars, to walk on the surface of our little ruddy buddy,” said Shostak, the director of the Center for SETI Research.

His experience accords with what many say is a distinct surge in public enthusiasm for space travel generally, and a manned mission to Mars in particular. Or make that a human mission: Women, too, are wholly on board.

“I would totally love to go to Mars,” said Pamela A Melroy, a former NASA astronaut who piloted two space shuttle missions and commanded a third. “We’ll get there,” she added. “I feel very strongly that we will.”

But the questions of when and who the “we” will be remain very much up in the air. Private companies like SpaceX and Virgin Galactic say they may get there first, or better, or more democratically.

Among the bolder if farther-fetched plans comes from a Dutch nonprofit venture called Mars One, which insists it will land four people on Mars – two men and two women – by 2025. As the project leaders see it, the technology needed to reach and colonise the red planet already exists, so why not go ahead and start loading the moving van?

There is a catch, they say. Where NASA-style flight plans are designed on the Apollo moonshot model of round-trip tickets, the “one” in Mars One means, starkly, one way.

To make the project feasible and affordable, the founders say, there can be no coming back to Earth. Would-be Mars pilgrims must count on living, and dying, some 140 million miles from the splendid blue marble that all humans before them called home.

Nevertheless, enthusiasm for the Mars One scheme has been of middle-school proportions. Last year, the outfit announced that it was seeking potential colonists and that anybody over age 18 could apply, advanced degrees or no.

Among the few stipulations: Candidates must be between 5-foot-2 and 6-foot-2, have a ready sense of humour and be “Olympians of tolerance.” More than 200,000 people from dozens of countries applied. Mars One managers have since whittled the pool to 660 semifinalists.

Many space experts and Mars aficionados remain deeply skeptical about the programme’s odds of success. They point out that Mars One doesn’t build rockets or any other aeronautic equipment, as SpaceX does.

Nor does it have the tycoon portfolio of Virgin’s Sir Richard Branson. Others have complained that the group’s emphasis on the colonist selection process over financial or technical details of the mission is little more than a publicity stunt.

Karen Cumming, 52, a Canadian journalist and teacher who is among the Mars One semifinalists, said she recently met the Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who won fame on the International Space Station by singing David Bowie songs and showing the world how water behaves in low gravity.

“I told him who I was, and I asked if he had any advice,” Cumming said. “He said: ‘Be relentless in your questioning about the hardware. Astronaut selection is the least of their worries.’'

Choosing the right people for the expedition, he said, is not the least of their worries, but ultimately the only worry. The mission’s success or failure hinges on assembling a team of people who can live together in extreme circumstances, he said, “without losing their minds.”

The various reasons offered for sending humans to Mars, at a cost of billions if not hundreds of billions of dollars include elements both practical and profound, optimistic and dystopian.

Ellen Stofan, NASA’s chief scientist, said that for all the success of robots like Curiosity, sending humans to the surface “may be the only way to prove life evolved on Mars and what the nature of it is.”

And demonstrating that some form of life arose at least twice in our solar system would lend ballast to the argument that the universe teems with life. “We’re a species that explores and pushes boundaries,” he said.

“By exploring our own planet, we’ve developed technology to make our life more comfortable. Mars is the next logical step, the boundary to push, to make us more developed still,” Shostak said.

Least hostile environment

Scientists agree that of all the places in the solar system where a few expatriate earthlings might settle, Mars is the least hostile. It’s roughly one-sixth the size of Earth, but given its lack of oceans, it nearly matches us in landmass.

It rotates on an Earth-like tilt of 24 degrees and has seasons, the length of its day is similar to ours, and its soil is about 2 per cent frozen water, which in theory could be melted and put to use.

Its gravity is about 40 per cent that of Earth – enough to keep inhabitants from severe bone and muscle loss caused by long-term stints in outer space, but still of sufficient levity, said Norbert Kraft, chief medical officer for Mars One.

Yet Mars remains a forbidding, frigid place, with an average temperature of minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit and an unbreathable atmosphere just 1 per cent the density of Earth’s and consisting largely of carbon dioxide.

Colonists would live in artificial podlike habitats, grow vegetables in greenhouses and get their protein from insects. And if you plan on going outside, you must wear your spacesuit at all times.

“No more smell of fresh grass, or the ocean,” Melroy said. “Giving that up would be a huge deal.” Another sacrifice, said Stephan Guenther, 46, a flight instructor and software developer in Cologne, Germany, and a Mars One semifinalist, would be the sound of silence. “There will always be some sound in the background, because the life support systems have to run,” he said. “If there’s real silence on Mars, something is going very badly.”

Yet oh, how he wants to go to Mars. “I was not yet 1 year old when Neil Armstrong landed on the moon,” he said. “I was standing on the couch watching it on TV, and my mother wasn’t able to pull me away.”

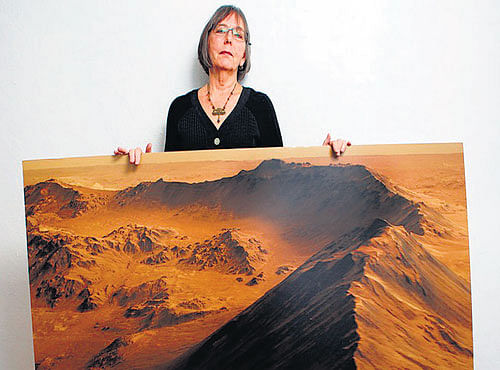

At 64, Jan Millsapps, a professor of cinema at San Francisco State University, is among the older candidates on the Mars One list. “I’m at a point in my life where I’m ready for a new adventure,” she said. “I don’t feel like I’m running away. It’s more like I’m running toward.”

Kellie Gerardi, 26, who works in the commercial spaceflight industry, says that even if Mars One never gets off the ground, it has already succeeded, elevating “the conversation about the need for space settlements to a global scale.”

Gerardi is planning to get married in September, and a NASA astronaut is to officiate at the ceremony. Yet she would be willing to leave her husband behind should a Mars passport bear her name.

Why doesn’t he apply to the programme, too? For one thing, she said, “he doesn’t think it would be fun.” For another, he’s an inch too tall.