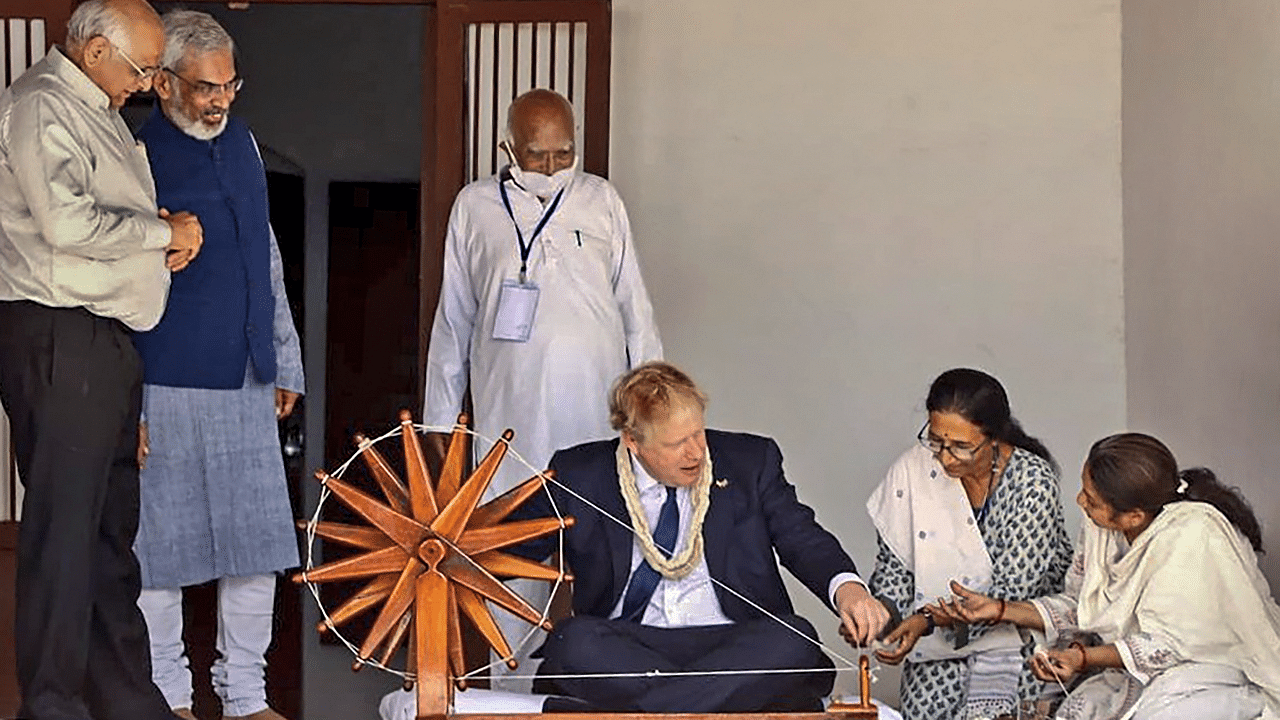

When the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s plane touched down at Ahmedabad airport Thursday morning, he became the first head of government from his country to visit Gujarat. It’s the state that birthed Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the man whose inspirational leadership helped end British rule in India. But while Johnson made the ritualistic visit to Sabarmati Ashram, it wasn’t Gandhi that drew him to Ahmedabad.

Instead, he’s the latest in a stream of foreign dignitaries summoned by New Delhi to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s home state, turning what started out as an admirable idea into an example of parochial promotion.

Until 2014, Indian diplomacy was almost entirely centred on New Delhi. Visiting heads of state and heads of government would visit the national capital, meet the prime minister, call on the president, hold other meetings and depart. Occasionally, if their team suggested a visit outside New Delhi, India would facilitate the trip — US President Jimmy Carter’s 1978 drive to the Gurgaon village that is now known as Carterpuri is an example. Some visited the Taj Mahal; others — like Queen Elizabeth II in 1961 — paid their respects to Gandhi at the Sabarmati Ashram. But, for the most part, India hosted leaders in New Delhi and focused on the nuts and bolts of diplomatic relationships.

Modi promised to change that and began inviting foreign prime ministers and presidents to cities in other parts of the country. As the former chief minister of Gujarat, it made sense for him to start with a city he knows well: Ahmedabad. In September, the bustling city hosted Chinese President Xi Jinping, and Modi served as a friendly tour guide. Meanwhile, the Modi government started another initiative — helping state governments engage directly with provinces of other countries on matters of trade and commerce. The Ministry of External Affairs started posting officers to state capitals — not only to Indian missions overseas.

The idea was simple and seemed laudable: Hosting leaders in multiple cities, rather than just New Delhi, would help cast a global spotlight on other parts of the country that might gain from the resulting tourism. States might find complementarities with their counterparts in other countries that New Delhi might not see. Why not let them build relations on their own and draw investments, the logic went?

But eight years after he took office, India’s prime minister appears to still think of himself as especially committed to Gujarat over other states. Consider the facts: Since 2018, Modi has hosted at least 18 heads of government or heads of state in his home state. That includes former US President Donald Trump, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, former Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa and Xi, among others.

The city visited most by foreign leaders after Ahmedabad? Varanasi, Modi’s Lok Sabha constituency. From Abe in 2015 and French President Emmanuel Macron in 2018 to Mauritius Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth this month, multiple top dignitaries have made trips to the ancient city by the Ganga since 2014.

Leaders from many Buddhist-majority countries have visited Bodh Gaya, but only rarely has Modi accompanied them. And several leaders stop by for a few hours in Mumbai for meetings with Indian corporate honchos, almost always without Modi by their side. Meanwhile, no prominent foreign leader has visited other states such as Bengal, Kerala, Odisha, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. These include both those states where Modi’s BJP is in power and those currently ruled by the opposition. At times, circumstances outside the government’s control have been responsible: A 2019 summit between Modi and Abe in Guwahati had to be called off amid protests in the city over the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act.

But the overwhelming choice of Ahmedabad and Gujarat as venues for diplomatic meets outside Delhi points to a clear plan. As Modi himself would say back in 2014, he was an outsider to New Delhi at the time. His claim to fame — or infamy, for his critics — was his rule in Gujarat between 2001 and 2014. By taking visiting world leaders to Ahmedabad, he could try and showcase the development projects he had led, demonstrate the economic energy of Gujarat and highlight his personal popularity among the public to try as indicators of what he hoped to accomplish across India. The idea, officials at the time told this writer and others, was to give visiting leaders a glimpse of what they could expect from Modi throughout the country if they partnered with him. The strategy, we were told, would help all of India.

Yet by repeatedly ignoring other parts of India while hosting world leaders, Modi has wasted a good idea. Eight years is enough time for him to be able to showcase successes in every state of the country. If Modi still needs to cite Gujarat as an example of what he can do, that’s a sign of a lack of confidence at best — and an admission of failure at worst.

(Charu Sudan Kasturi is a journalist.)

Watch the latest DH Videos here: