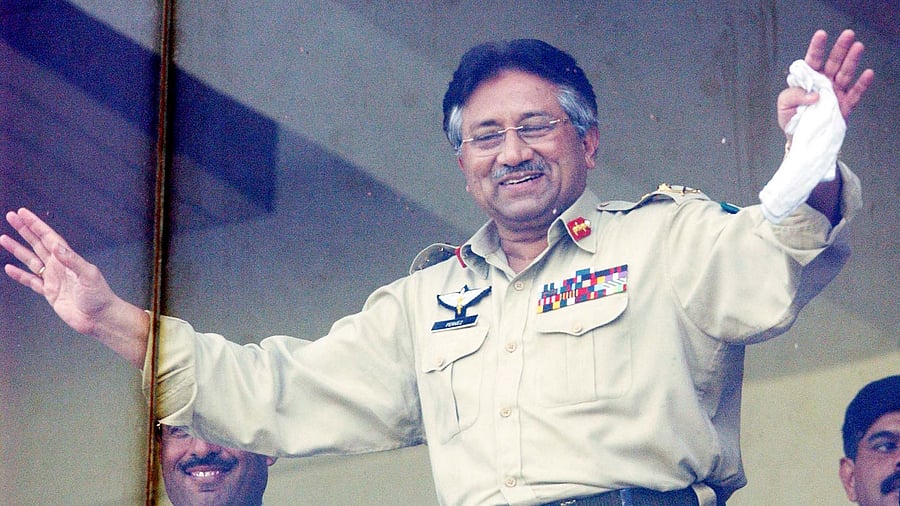

Pervez Musharraf was in the air. He was a highflyer, becoming Army General of Pakistan at the age of 56. Yet, as he flew at 35,000 feet in the air, he also wanted to be grounded.

This was in October 1999, and Musharraf was in Sri Lanka on an official visit. He owed his military appointment to then Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, who gave him the job superseding two senior-ranking officers. Yet, when he got wind of his imminent sacking by Sharif, Musharraf did not think twice. He got back to Karachi and what followed was yet another military coup in Pakistan’s chequered political history.

Coups And Wars

History was about to eerily repeat itself with another military coup when Musharraf ousted Sharif. It was redolent of the time when Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was ousted by Zia-ul-Haq. But this was a bloodless coup; Sharif’s life was spared.

Musharraf was the new czar. He had gone against the tide becoming the first muhajir (Muslim emigrant from India) to get the top job in uniform, a position that had been held by ethnic Pashtuns and Punjabis until then.

His ideological moorings, pugnaciousness, and the quest for one-upmanship with India started early in his life. He was a young officer who saw the 1965 India-Pakistan war, and was a commando during the 1971 war, but what left an indelible scar on Musharraf’s ego and psyche was the ‘defeat’ in the 1984 Siachen Conflict after Indian armed forces captured the Siachen Glacier as part of Operation Meghdoot.

That ineffaceable feeling for Musharraf also saw him concoct the insidious plan of staging the Kargil War.

Janus-faced Musharraf

The brazenness of starting a war is one thing, but doing so, after both India and Pakistan went nuclear was reckless. Exacerbating the situation was the fact that late Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in his overtures of peace, took the bus to Lahore, signed the Lahore Declaration at the Minar-e-Pakistan, the very symbol of Pakistan’s founding thereby assuaging hardliners in Pakistan that India had indeed accepted the state after Partition. As the ink barely dried on the declaration, Musharraf was hatching his mendacious plan.

When that failed, and it became evident to Islamabad, New Delhi, and Washington, as to who cooked the diabolical treachery, Musharraf was on thin ice.

For the incursion of Kargil heights, Musharraf could have easily been persona-non-grata in India. However, Vajpayee tried to reset ties with Pakistan by inviting then Pakistan President Musharraf to India for the Agra Summit in July 2001. On a hot day in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, Vajpayee sat across Musharraf. It could have been that seminal summit, but like many other India-Pakistan dialogues, it was high on media coverage, low on policy concurrence.

Musharraf smiled like a diplomat, but he was a military man, trained in warfare, and knew that battles seldom follow a script. So, he went off script and held meetings with the Hurriyat Conference, visited his childhood home in Daryaganj with a visit to the Jama Masjid, and then the Taj Mahal. Psychological warfare is a commando’s asset.

Relations didn’t exactly thaw. The December 2001 Parliament attacks by Lashkar-e-Toiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad — both of which received patronage from sections of the Pakistan State — led to a tense border standoff in 2001-2002 dubbed ‘Operation Parakram’.

Dictator’s Luck

History does repeat itself. Like his dictator predecessor Zia-ul-Haq, Musharraf too had a geopolitical change to his advantage. Ideally, these squalid dictators should have been reviled ad-nauseum by the West, but Afghanistan was their trump card. If for Zia-ul-Haq it was the Soviet presence in Afghanistan that endeared him to Washington, for Musharraf it was the Al-Qaeda and the hunt for Osama bin Laden.

It was the best of times and the worst of times for Musharraf. He pledged allegiance to the United States’ War on Terror, hence setting fires in Pakistan. He played the George W Bush administration for a fiddle, promising to defeat Islamic extremism, and insisting till the very end that bin Laden wasn’t in Pakistan. We know how that turned out.

He got new military toys from Washington, and the Pakistan army’s coffers were flushed, but that came with a price with several assassination attempts as he navigated a slippery slope between militant Islamists at home and a diplomatic façade for the West.

The Downfall

He inadvertently architected his own downfall when he demanded the resignation of Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudry, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, charging him with abusing his office. The pot called the kettle black and that sparked off protests from the legal fraternity, leading to cracks in Musharraf’s political edifice.

In 2008, he was allegedly complicit in not providing former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto with adequate security, as she was assassinated during a rally. Her son, current Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto has held Musharraf responsible for his mother’s death.

Musharraf may not believe in karma, but it’s funny to find a way to explain how Musharraf had to flee Pakistan in 2008 and Sharif became Prime Minister for the third time in 2013. Musharraf had a few dalliances with Pakistan’s politics between 2013 and 2017, but none bore fruit as by then he had become persona non-grata.

Musharraf died on February 5 while living in exile in Dubai. It is a cruel irony that for a powerful military general-turned-dictator politician, Musharraf spent more time of his life in exile than as President of Pakistan.

It is said that one should not speak ill of the dead; in Musharraf’s case that’s a challenge.

(Akshobh Giridharadas is a Washington DC-based former journalist.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.