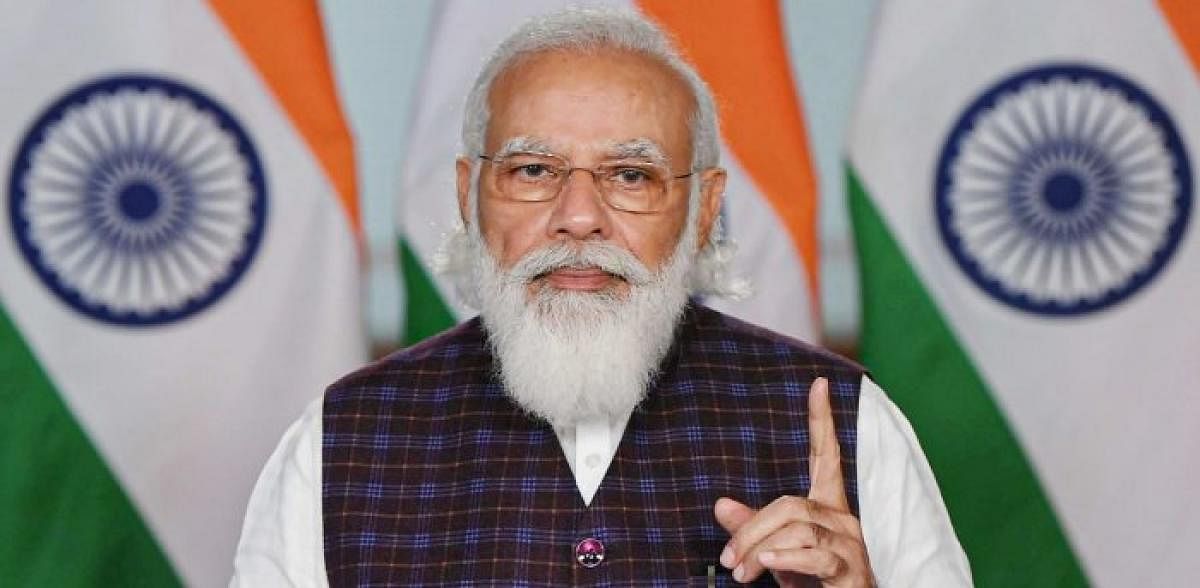

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call for reforming and strengthening the World Health Organisation (WHO) to “build a more resilient global health security architecture’’ is timely and relevant. He made his views known at the second global Covid-19 summit hosted by the US and other countries last week. There have been calls from time to time for reforming WHO. Its handling of the Covid pandemic has made these calls more urgent. The world health body was found wanting in many respects at a time when its leadership and guidance was crucial in the global fight against the pandemic. A panel appointed by WHO has itself criticised the organisation for its lapses, saying it failed to advise the world in time on the steps to be taken to prevent the pandemic from spreading in the early stages. There was also a delay in declaring the pandemic a global emergency.

WHO’s failure in investigating the origin of the novel coronavirus, traced to Wuhan in China, has come under intense and detailed scrutiny. China blocked the investigation and refused to cooperate with the world health body, but it is widely felt that WHO was lax in its efforts. This has raised doubts about the credentials of its leadership. One key reform could be about putting in place a leadership which is immune to pressures. There is also the need to give more powers to WHO for use in such situations. There should be room for it to take prompt and effective action in health emergencies. It should have powers to seek information from member countries about major disease outbreaks and to ensure that right action is taken by them. The system should ensure that poor countries are not discriminated against in the case of vaccines and treatment. WHO’s failures have highlighted the need for financially strengthening it. Its funding structure is skewed now with voluntary contributions accounting for much of the budget. This results in financial uncertainty which can affect its functioning. The reforms should facilitate better handling of public health emergencies by member countries. They should be formulated so as to meet the needs of all countries, big and small.

The Prime Minister’s specific suggestion for "streamlining WHO's approval process for vaccines and therapeutics’’ may have come from the thinking that the Emergency Use Listing (EUL) of Covaxin, made in India, was unnecessarily delayed by WHO. This is a wrong perception, and WHO can’t be faulted in this respect. But his call for “building a resilient global supply chain for equitable access to vaccines and medicines’’ is sound and welcome.