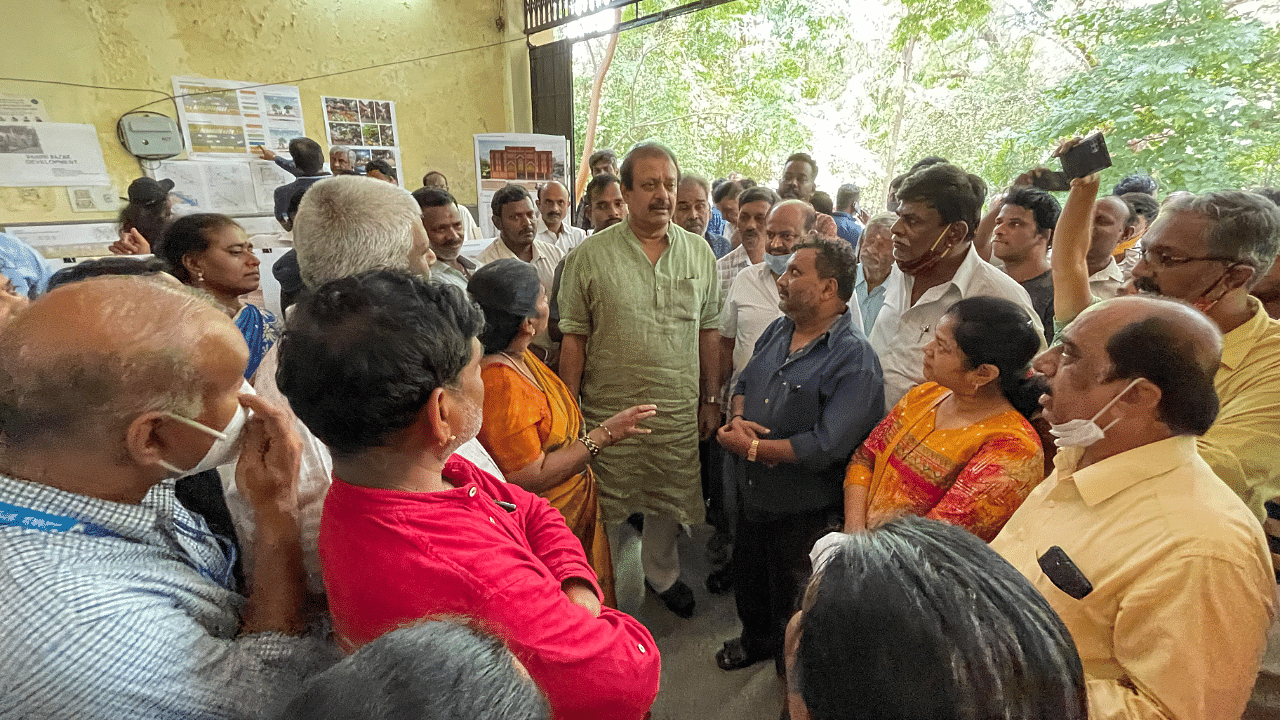

Recently, there was mayhem at a public consultation meeting facilitated by the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) and the Directorate of Urban Land Transport (DULT) in Gandhi Bazaar in South Bengaluru. The meeting was regarding a plan to revitalise/pedestrianise the 130-year-old Gandhi Bazaar. Gandhi Bazaar is a street market that is congested with narrow footpaths taken over by vendors and pedestrians, poorly managed, and clogged with vehicular traffic. The BBMP and the DULT have been working on the revitalisation plan for over 10 years now. Labelled as a public participatory process, the process has come under significant criticism. The media, vendors and residents in the area have called the plan flawed and problematic, and destructive of the heart and soul of the market. A plan to pedestrianise the area has been opposed.

And yet, to all purposes, this was a positive sign. There is anger; there are claims and counter-claims; groups of stakeholders have developed alternative plans countering the official plan. This is good news, especially in a landscape like India’s, where the public urban development process barely engages with stakeholders. Token public consultative noises are made but the government usually does exactly what it wants to do, regardless of the people’s opinions.

In the Gandhi Bazaar project, the BBMP is asking people to engage with them. This reflects a democratic approach to review political-bureaucratic decision-making mechanisms requiring increasing participation of social actors in the political process. The process is messy, complicated; egos will be hurt; fights will be had -- but this is the way to go.

The process is iterative. Plans need to be drawn up, critiqued and torn up; redrafted, torn up again, and drafted yet again. Everyone -- young, old, weak, strong, little and big -- must have their say. Some will say it loudly; some quietly; some angrily and some from behind a computer screen. But the space for this language must be made.

The process itself may take days or months or years, but finally a plan will come together. It may not be the best but at least, it will have been discussed by people that live in that space -- a public consultation in its real form. And a new market space will emerge.

The Gandhi Bazaar project itself has severe flaws in it. The initial survey of over 300 stakeholders indicated that 81% felt that pedestrianising the area would reduce incomes. Most felt that stopping vehicular traffic through Gandhi Bazaar’s main road would change the nature of the area, and they opposed it. Suggestions included a solid waste management plan, utilisation of a vacant government property for parking and streamlining of traffic.

Unfortunately, these suggestions are not reflected in the plan presented by the government. Despite opposition from the beginning, a plan for pedestrianisation has been presented. The project’s primary engagement relates to land acquisition and construction for parking facilities, a market for vendors, and some road widening on parallel roads. This, to some extent, indicates how public officials and technical experts most often focus on the technical aspects of a decision and dismiss local knowledge.

Is there a way to remedy this process? Yes, there is. This involves streamlining and institutionalising the consultative process as part of all development projects. In Gandhi Bazaar, the process started well. But the recommendations of the initial survey highlighting the community’s concerns, which should have helped the officials in power to make informed decisions, appear not to have been listened to. Often, the outcomes of a survey can be unspecific but provide a reasonable direction for sustainable development. A public consultative process should heed the demands of stakeholders and provide solutions within their frameworks, rather than present a pre-determined approach. Currently, the Gandhi Bazaar stakeholders have presented a plan with traffic management options. BBMP and DULT should use this material, return to the drawing board, and present options that value these demands. This will be a meaningful consultative process.

If we are truly lucky, there will be more engagement with the government on more projects. After all, Bengaluru is awash in project development -- almost 16 markets are in line to be redeveloped under the Smart City programme, and potentially there will be more. This messy process, streamlined and with attentive listening to people, needs to be replicated across the city, state and country for a truly participatory process to emerge. Citizen participation is the critical difference between going through the empty ritual of participation and having the real power needed to affect the outcome of the process.

(The writer is a Bengaluru-based urban planner)