Credit: Special arrangement

“I neither knew nor cared about the water wastage in our village or the over-extraction of ground water. Nor did I ever want to monitor rainfall with a rain gauge. Thinking about such issues never occurred to us. We only knew that our village faced water shortages round the year, and we look towards the government to bring us some succour,” says Dhruv Singh, who hails from Abu Road in the remote tribal-dominated district of Sirohi, located in the southern part of the desert state of Rajasthan.

Telpur, a tiny village with a population of over 2,000 (2011 Census) in the Pindwara block of Sirohi, had groundwater at a depth of 25 feet about 30 years ago. Now it has receded to about 100 feet. Most blocks in Sirohi district over exploit ground water. According to the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) report on Dynamic Water Resources of Rajasthan, 2020, four out of five blocks of Sirohi, barring the Pindwara, are over-exploited. Sirohi district, with overall ground-water extraction at about 128%, falls under the over-exploited and semi-critical category.

Nenu Devi, 58, a resident of Telpur, told the DH: “When I was young, we used to get water easily at around 20–25 feet. But today it has gone below 100 feet. The situation is alarming, but we had no idea of the receding water table until a workshop, and some easy water exercises helped us realise water criticality in years to come.”

Experts say climate change, including changing nature and patterns of rainfall, increasing pressure of population and livestock on the water resources, and depletion of environmental resources, has led to the decline of the water table. This process has been further intensified by the depletion of forest cover in hilly areas, acceleration in soil erosion, and siltation of river channels and water reservoirs. Consequently, the drinking water crisis, along with the shortage of water for irrigation and other purposes, is being felt now.

A major portion of the Sirohi district is inhabited by the backward tribal communities of the Bhil, Meena, and Garasia tribes, which account for over 43% of the total population. Most inhabitants are unaware of the urgent need for a water security plan.

For Rajasthan, the most water-deficient state in the country, every drop is precious. With a short spell of monsoon coupled with scanty rainfall, drought is the most frequent disaster recurring in the state. The state has witnessed frequent drought and famine conditions in the past 60 years.

Rajasthan is also among the states with the greatest climate sensitivity and the lowest adaptive capability. The state has only 1.16% of India’s total surface water resources, or 21.71 billion cubic metres (BCM); however, only 16.05 BCM of this is economically usable. Hence, it is imperative for the state to have a sustainable water security plan.

Water balance, budgeting

In Rajasthan, surface water resources are inconsequential, and the entire state depends primarily on groundwater. Around 91% of the domestic water requirements are being met from groundwater sources, and only 9% of the water requirements are being met from surface water sources, says a research paper on water resource management in Rajasthan by Pravin Kumar, from the Department of Geography, T N B College, Bhagalpur. The report also states that about 80% of the total irrigation water demand and most of the industrial water requirements are being met by groundwater resources alone. Thus, meeting the various sectors’ demands and providing safe water to people are the most challenging tasks for state planners.

With steadily depleting levels of groundwater and low precipitation, water conservation assumes critical importance. A unique water conservation experiment is being carried out in Telpur village with the involvement of villagers. The priority is to make them realise the importance of conserving every drop of water.

What is interesting is that the villagers are learning to maintain the water balance, budget, and ration water through simple games and quizzes.

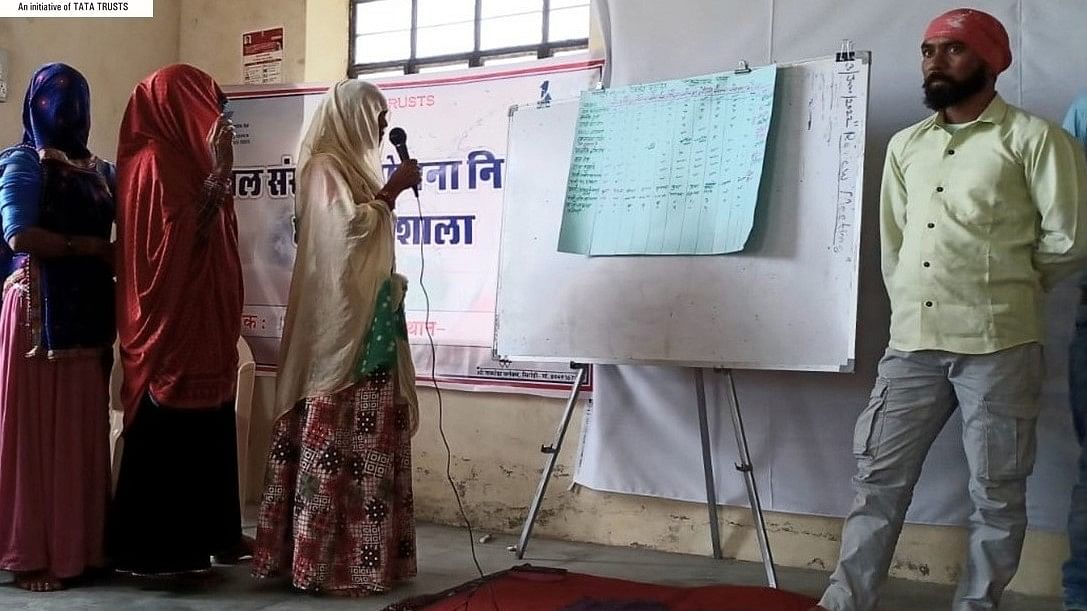

The ongoing workshop called Jal Tula encourages community participation. An organisation called the Centre for Micro-Finance (CmF), which has initiated the programme in Sirohi district, works on the idea that if communities are not involved in decisions being made, they are not able to link development initiatives to their lives and livelihoods.

“Water resource management is incomplete without community participation. The end user has to be made aware of the availability, usage, and balance of water resources through this process. A water conservation system can be self-sustaining only when it is built around the community’s desire for a better life. And solutions to the macro problem of natural resource management and climate change can actually be found at the micro level—on the field, within individual households, and especially among women. Community participation is no guarantee of success, but without it, we are bound to fail,” says Malika Srivastav, executive director of CmF.

So CmF started off by encouraging the community to prepare their village-wise water budget for attaining water security. Around 40 local villagers were selected to participate in the workshop; rapport building and sensitization followed, and they were asked to assess the water balance of the village and follow water budgeting.

The yields of the wells were measured, and water usage for drinking and cultivation was assessed. The concept of the rain gauge and the importance of rainfall monitoring were explained to the volunteers. They were asked to identify leaking pipes and dripping taps and assess water waste. Then they were tasked with thinking of solutions.

Subsequently, the villagers observed the details of their drinking water supply, their agricultural practices, cropping pattern, water consumed for irrigation and domestic purposes, and wastage of water supplied.

One of the volunteers, Leela Devi, 39, said: “Earlier, we did not bother about leaking pipes and dripping taps. But at the workshop, we realised the unnecessary loss of water. All women members then took the initiative to identify such leakages and get them repaired.”

To make the villagers understand water budgeting, they were asked to prepare budgets for marriages and assess the income of the village from agriculture, and women were especially asked to measure domestic water requirements. The demand and supply of water required by the entire village were also assessed, and the amount of water wasted was calculated.

The workshop revealed that a staggering amount—around 58%—of the water supplied to the village was wasted. The villagers were explained the need to monitor the water levels and fluctuations and also monitor the drop in water levels during a certain period.

There were exercises on preparing budgets for marriages to help understand the concept of budgeting. Villagers rallied that the first and foremost thing to do was to curb water wastage at all levels, like domestic tap connections, leakages, excessive flood irrigation, irrational cropping patterns, and the need for water harvesting, conservation, and recharge.

It was observed that not much surface water was available for use within the village, and no canal system was available in the village. Groundwater was the main source of water for both agriculture and domestic usage. Few of the anicuts constructed were damaged and didn’t hold enough water. None of the streams in the vicinity of the village were perennial.

Deva Ram, 65, was an enthusiastic participant. He realised that groundwater may not be available for future generations, and consequently, they would have to move out in search of greener pastures. He quipped, “The Jal Tula exercise of finding the water income and expenditure of our village was something new. On the basis of the results, we planned our supply-side intervention and proposed making new anicuts and other water harvesting structures.”

The villagers were asked to collate information regarding cropping patterns, water usage, expenditures incurred, and net income generated from different crops. The task assigned for water usage in the agricultural sector revealed that 84992 tanks were used for irrigation annually. Wheat, cattle feed, and chillies were seen as major water-consuming crops.

Villagers have been motivated to install water metres for all house tap connections. Water committees have been set up to chalk out plans for achieving ODF status through self-regulation and also improve drainage within the village by taking advantage of government schemes. Committees have been asked to maintain the health cards of all inhabitants.

Meanwhile, farmers in Telpur did not maintain an accurate record of their expenditure on growing a crop. Therefore, they did not know the actual profit and loss incurred from agricultural activity. It was explained that keeping a record of such expenditures and water consumed was important for choosing low-water-consuming and high-return crops.

It was observed that the water consumption of the village was more than 500% of the available resource.

Volunteers, in turn, sensitised other villagers, who have now become aware of the grave situation. Inspired by Telpur, at least 34 other panchayats have resolved to work on water budgeting and security.

Traditional conservation methods

Water scarcity, however, has always dogged this desert state.

There are hundreds of small and medium water conservation techniques that have helped the state survive its harsh climate for centuries. Among these, jhalara, talab, bawar, tanka, ahar pynes, johads, khadins kund, baoli, bhandara had, nada, and nadi are structures mostly found in western Rajasthan. Roof rainwater harvesting is another modern technique to recharge the groundwater. But each of these is a definitive system.

A scientific paper authored by Dhruv Saxena of JNV University Jodhpur, titled Water Conservation: Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Systems in Rajasthan, talks about the various traditional water resource systems. He says that water is such a scarce commodity in the arid regions that any natural resource is literally a pilgrimage.

Wells are an important source of water. A kua is usually owned by an individual, but there are larger wells, known as kohar, owned by the community. Then there are step wells called baolis or jhalaras. Baolis usually have religious significance and were constructed as a philanthropic deed for punya. In Rajasthan, certain areas are known as par, a place where the flowing water accumulates and seeps into the earth. So the villagers know that if a shallow well was dug there, sweet water would be found. They can also identify a par by the foliage growing there. They would then dig beris (shallow

and narrow wells about 6–8 m deep) to collect this par water.

The people of Rajasthan traditionally divide the entire state into two areas, one with palar water and the other with wakar water. Palar is rainwater, which is the purest form of natural water and can be stored in tanks for three to five years. Wakar water is underground water that has oozed out of the earth and has minerals dissolved in it.

Rooftop harvesting is common across the town and villages of Thar. Rainwater that falls on the sloping roofs of the houses is taken through a pipe into an underground tank, the tanka, built in the main house. This technique of harvesting has been perfected to a fine art in western Rajasthan. The first spell of rainwater would not be collected as it would be used to clean the roofs and pipes. Subsequent rainwater would be collected in underground tanks.

Traditionally, tankas were the most reliable methods of water harvesting in desert towns. Tankas were used judiciously so that their water was easily available in the summer. Whenever there was less rainfall, household tanks would be filled up with water from neighbouring talas, nadi, or village ponds.

No water laws in Rajasthan

Water expert and director of the Centre for Environment and Development Studies, Dr M S Rathore, however, said the government is not alarmed by the receding groundwater level. He explained: “Despite the latest report that 219 blocks out of a total of 302 blocks in Rajasthan were over-exploited, the government is not bothered and is sanctioning new tubewell connections for irrigation. Rajasthan, as of now, has no law on underground water management. Whichever party may be in power, they are careful not to antagonise the farmers because of vote bank politics.”

Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra have Acts on Underground Water Management, but Rajasthan till now only has a draft bill prepared in compliance with the formation of the Ground Water Conservation and Management Authority for the proper use of groundwater and the convenience of industrial units in the state.

Moreover, the Ashok Gehlot government launched a welfare scheme named Rajasthan Mukhyamantri Nishulk Krishi Bijli Yojana, which will provide free electricity to farmers whose consumption is within 2000 units per month.

Earlier, the government was providing electricity to farmers at 90 paisa per unit. This scheme is expected to benefit 11 lakh farmers in the state.

Rathore added, “So one can imagine how much underground water is being overexploited. Moreover, there are no strict laws to arrest declining water levels and the degrading quality of water. Frankly, does anybody really care about water conservation?”