Did you meet God? This was a question Rakesh Sharma, the first Indian to travel into space, often faced from admirers at home after he returned to Earth in 1984. “I would say, no, I hadn’t met God,” he says.

More than three decades later, fact and fiction blur easily with his modern-day fans when they meet Sharma, 68. “Now many young mothers introduce me to their kids and tell them, ‘this uncle has been to the Moon!’”.

But Sharma can never forget the hysteria after he returned from space. He criss-crossed the country and lived in hotels and guest houses. He posed for pictures and gave speeches. Elderly women blessed him; fans tore his clothes and sought autographs.

Politicians paraded him in their constituencies for votes; and authorities sent him on holiday to a national park in searing 45°Celsius temperatures. “It was completely over the top. It left me irritated and tired. I had to keep a smile on my face all the time,” he recounts.

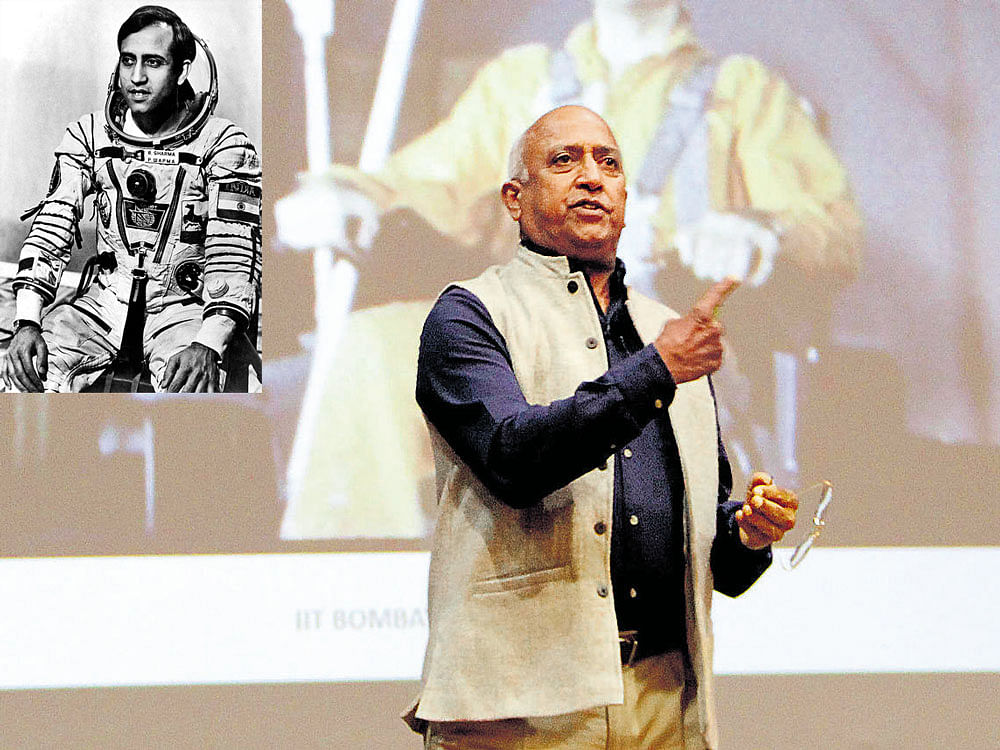

Sharma wears his achievements and fame lightly. He joined the Indian Air Force at 21 and began flying supersonic jet fighters. He had flown 21 missions in the 1971 war with Pakistan before his 23rd birthday. By 25, he was a test pilot. He travelled into space at 35, the first Indian and the 128th human to do so.

“I had pretty much done it all before I went into space. So when the opportunity came, I went along. It was that simple.”

What is easily forgotten is that Sharma’s feat was possibly the only silver lining in what was one of independent India’s worst years ever. 1984 saw the Indian army storm the Golden Temple in Amritsar to flush out Sikh separatists and the revenge killing of then prime minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards.

The anti-Sikh riots, the country’s worst religious rioting after Partition, convulsed Delhi. And, before the year had ended, thousands of people in Bhopal had been killed after toxic gases leaked from a chemical factory, the world’s worst industrial accident.

In a wounded nation, a young pilot shone as an unlikely beacon of hope. Indira was pushing for an Indian in space before the 1984 general elections, and dialled her closest ally and space race leader, the Soviet Union, for help. The latter asked for a list of candidates.

Sharma was picked to undergo a battery of gruelling tests from a reported shortlist of some 50 fighter pilots. Among other things, he was locked up by the air force in a room with artificial lights at an aerospace facility in Bengaluru for 72 hours to test for “latent claustrophobia”. In the end, two of them were selected for the final training in Russia.

More than a year before the launch, Sharma and Ravish Malhotra travelled to Star City, a high-security cosmonaut-training facility some 70 km from Moscow, to train for space flight as there were no such facilities at home. It was bitterly cold. He trudged in the snow from one building to another: “It was very Dr Zhivago”.

He had to learn Russian quickly as most of the training was in that language. Six to seven hours of language classes every day meant that he had mastered enough Russian in three months. He was put on a carefully controlled diet of local food, capped at 3,200 calories a day. Olympic trainers tested him for strength, speed and endurance, and how his chest stood up to punishing G-forces.

Midway through the training, he was told he was the chosen one, and Malhotra would serve as backup. “It wasn’t such a big deal, it wasn’t very tough,” says Sharma, modestly.

But many, like science writer Pallava Bagla, believe Sharma’s feat was a “huge leap of faith”. “He came from a country which didn’t have a space programme. He didn’t dream of becoming an astronaut. But he travelled to an alien environment, endured a harsh climate, learnt a new language, and trained hard. He’s a real hero.”

On April 3, a Soviet rocket carrying Sharma and two Russian astronauts, Yuri Malyshev, 42, and Gennadi Strekalov, 43, left Earth from a spaceport in the then Soviet republic of Kazakhstan. “The take-off was boringly routine. We were over-trained by that point,” Sharma recounts. “I was the 128th human in space. 127 people had come back alive. So I didn’t really sweat about it.”

Two years later, in 1986, the Challenger space shuttle broke apart over a minute after its launch, killing all seven US astronauts in flight. Sharma is now among the more than 500 fortunate people who have travelled into space since Yuri Gagarin’s single orbit of Earth in 1961.

The media gushed how the joint flight was the high noon of the Soviet Union-India friendship. Soviet news agency Tass filed a report saying Sharma’s mother, a teacher, had developed a “general interest” in the Soviet Union after her son was chosen for the flight in 1982. “The mission,” says Sharma, “was scientific in content, but with a political end at home.”

Tragically, Indira would be murdered within eight months, and her son, Rajiv, would sweep the polls at the end of the year on a sympathy wave for his mother. The space flight wasn’t needed to fetch votes for the ruling Congress.

Many firsts

Sharma and his fellow astronauts spent nearly eight days in space: grainy TV images from the time show the three men, in grey jumpsuits, floating around in the Salyut 7 space station, and conducting experiments.

He became the first human to practice yoga in space — using a harness to stop him from floating around — to find out whether it could better prepare crews adapt for the effects of gravity. He spoke to his family once on a live link with 2,500 people in the audience in a Moscow auditorium.

When Indira asked Sharma, on a hazy live link, how India looked from space, he delivered a line in Hindi which would have easily become a viral tweet today. “Sare Jahan Se Acha,” he said, quoting from a famous poem by Mohammad Iqbal, which he had recited every day in school after the national anthem.

“It was top of recall. There was nothing jingoistic about it. India does look so picturesque from space,” Sharma told me.

“You’ve got this huge coastline, the lovely blue ocean on three sides. Then there are the dry plateaus, forests, river plains, golden sands of the desert. The majestic Himalayas looked purple because sunlight cannot get into the valleys. Then there were snow capped mountains. We’ve got everything.”

The New York Times presciently wrote that “India is not likely to have its own manned space programme for a long time, if ever, and Sharma’s flight may well be the last by an Indian for a long time.” Forty-three years later, Sharma remains the only Indian to travel to space.

After his space flight, Sharma returned to his life as a jet pilot. He flew Jaguars, and the fighter jet Tejas. Then he switched gears, working as the chief operating officer of a Boston-based company which made software for manufacturing planes, tanks and submarines.

Eight years ago, the space hero retired and built himself his dream home, with sloping roofs, solar-heated bathrooms, harvested rainwater, handmade bricks excavated from the plot, and a sunlit study stacked with his favourite books and music. He lives with his interior designer wife, Madhu, and their pet dog, Kali. A Bollywood biopic is “in the works”, with star Aamir Khan rumoured to play the astronaut.

Would you like to return to space again? I ask. “I would love to,” he says, looking out to the hills from his sprawling balcony. “But this time I would like to go as a tourist and savour the beauty of Earth. There was too much work when I went up there.”