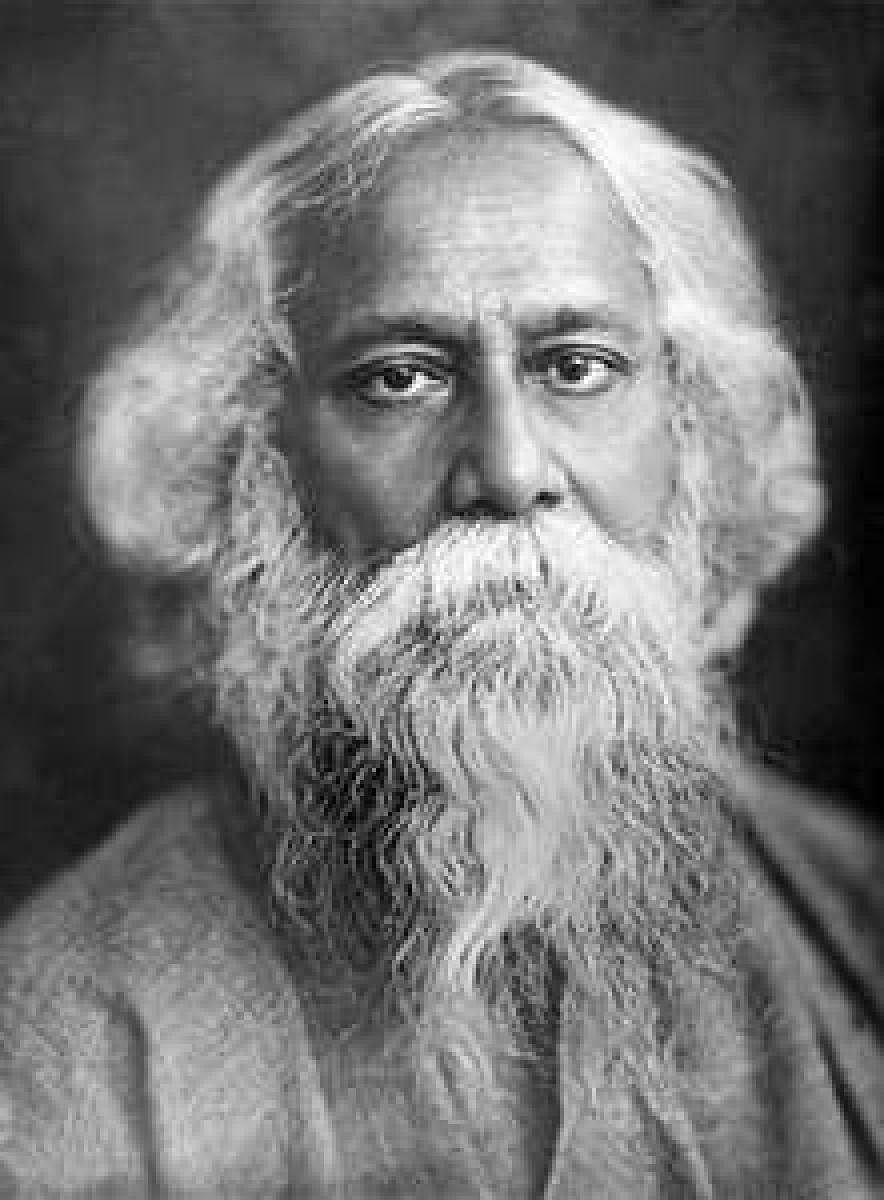

It is not easy to walk with a poet like Rabindranath Tagore, particularly when our prosaic intellect breeds cynicism, and drives us towards temporal pleasures. Yet, in a deep moment of contemplation we realize that a poet like Tagore — with his prayers and spiritual longing, communion with the spirit of nature, and penetrating reflections on the human consciousness amid the flow of a civilisation — ought to be invoked time and again to remind us of our potential sanity and divinity.

Yes, while the Upanishadic longing for the universal and the transcendental can be seen in the sublime prayers of Gitanjali, his essays on the discontents of the ideology of bounded nationalism would reveal his quest for the creative flow of the human spirit. Likewise, his short stories, songs and novels make us pass through the peaks and valleys of existence — life and death, love and pain, and temporal and eternal.

On his birth anniversary, as I recall the poet with a deep sense of gratitude, what immediately strikes my mind is that he sought to give us the psychic/political strength to see the limits to the discourse of modern nationalism. Even if the ‘nation’, as Benedict Anderson said, is an ‘imagined community’, it does have tremendous impact on people’s consciousness. War, genocide, colonialism: every act of violence is legitimised in the name of what Tagore would have regarded as ‘idolatry of the Nation’. Its inherent narcissism, its borders and boundaries, and its drive towards homogenisation of consciousness cause violence, and transform human subjects into soulless cogs of a hyper-masculine machine.

Tagore repeatedly reminded us of this ‘spectre of barbarity’; and his pain or anguish was quite visible in Crisis in Civilization — the last convocation speech he delivered at Santiniketan in 1941. Possibly, as social psychologist Ashis Nandy has argued brilliantly in Illegitimacy of Nationalism, some of the female characters Tagore portrayed —Anandamayee in Gora, Nandini in Red Oleanders, and Ela in Four Chapters — reveal the life-affirming power of the feminine that help us to see the hollowness of hyper-masculine nationalism.

Tagore’s celebration of the rhythmic thread of connectedness amid plurality and heterogeneity, patriotism and universalism, and finite and infinite made him uneasy with all sorts of limiting identities. And his creatively nuanced critical engagement with Mahatma Gandhi makes it clear why, despite his admiration for the Mahatma, Tagore could not give his consent to ‘non-cooperation’ and ‘swadeshi’. And despite these occasional differences, Gandhi trusted Tagore as his Gurudev; and his song Ekla Cholo Re gave Gandhi the spiritual strength to walk through the villages of turbulent Noakhali in 1946. It is sad that in our times, characterised by majoritarian mighty nationalism and simultaneous stigmatisation of the religious minorities, we have almost forgotten what the creative interplay of Tagore and Gandhi could offer to us.

Religion, as contemporary social reality indicates, has become merely an identity-marker; orthodox priests or clergy and militant nationalists have killed the spiritual flavour of religiosity -- our finest prayers, or, to use Tagore’s phrase, our ‘surplus’, our non-utilitarian urge to break all walls of separation, and feel the touch of the infinite even in the finite domain.

‘A poet’s religion’ seeks to arouse the feeling of gratitude; we overcome the anguish of disenchantment, and with deep aesthetics a river becomes a river, a tree becomes a tree, or a bird becomes a bird. We relate. We communicate. We see ourselves in the play of creation. We feel what Francis Bacon’s empiricism or Rene Descartes’s rationalism could not grasp. Only then is it possible to sing in tune with Tagore:

I feel the tenderness of the grass in my forest walk,

The wayside flowers startle me.

That the gifts of the infinite are strewn in the dust

Wakens my song in wonder.

Is it that we have missed this song at a time when religion has been degenerated into the cacophony of Jai Shri Ram, or the death wish of a ‘suicide bomber’? Everything seems to have become its opposite. Noise is music; violence is religion; and the divine is the burden of dead ritualism. In a world of this kind, is it possible to understand the poet?

Yes, Tagore was a poet of an altogether different kind. He was a visionary, an artist, and above all, an educationist. His experiments at Santiniketan — possibly, a modern tapovan filled with aesthetic sensibilities and vibrations of universalism — generated a possibility of redefining education. True, in modern times, schools look like cages or prisons dissociated from what is natural to the child: her spontaneity, her abundance, and her affinity with birds, trees and monsoon clouds. Tagore felt the pain of burdened childhood oppressed by bookish knowledge and the dead weight of information.

In a way, like Rousseau, Tagore too saw nature as a great educator. Hence, relatedness with nature, unity of ‘work’ and ‘play’, and education as an aesthetic articulation of the inner quest characterised the poet’s school. Its appeal was tremendous; it nurtured artists like Nandalal Bose; and Gandhi, despite his busy schedule, managed to find time to come to this ashram, and get Tagore’s blessings. It was a project that aimed at creating a new being: not a violent conqueror or an ‘exam warrior’, but a wanderer with prayers and in communion with the spirit of the infinite.

It is, however, a different story that we failed to learn anything significant from this experiment. At a time when Kota — a notorious town in Rajasthan known for the lucrative business of all sorts of coaching centres — emerges as an educational site, the message that we convey is clear: a poet has no place in a world that sees nothing beyond the market-driven ideology of ‘success’.

Yet, even amid the culture of socio-political decadence, the poet whispers in our ears, and urges us to see what ought to be seen.

(The writer is Professor of Sociology, JNU)