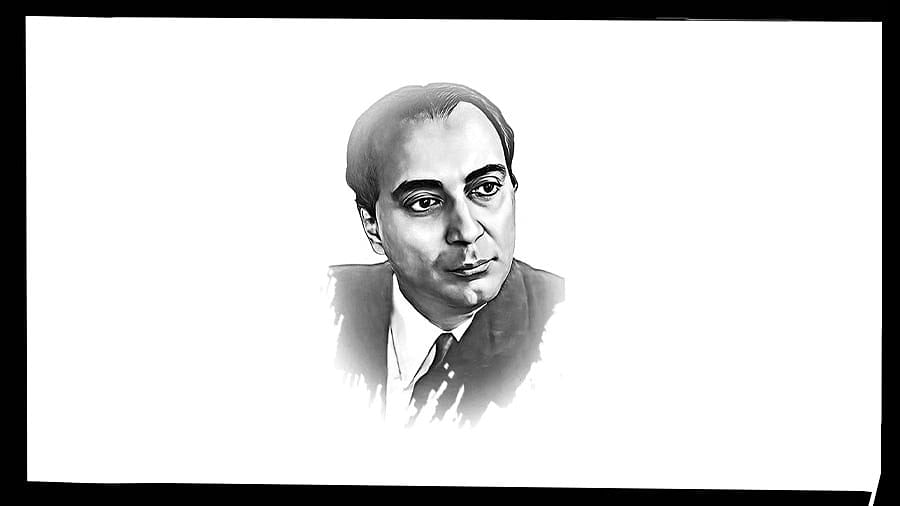

Credit: DH Illustration

America’s Robert Oppenheimer, British Nobel Prize winner Patrick Blackett and India’s Homi Bhabha were kindred spirits. All three were physicists trained at the legendary Cavendish Laboratories in Cambridge, and each played a key role in developing nuclear weapons for their respective countries.

Trying to make sense of Bhabha’s contribution was at the heart of my university research and the 50th anniversary of India’s nuclear test was a reminder of the banging on my Oxford college door on May 18, 1974, when my American friend Thomas shouted out just after 3 am, “Shyam, they’ve done it. India has tested the Bomb.’

I used to call him Doubting Thomas because he was among those close university friends who questioned my conviction that, despite its enduring image of bullock carts and impoverished peasants, slow and steady India was now sufficiently sophisticated to test an atomic bomb.

That conviction was based on a series of Oxford-funded visits to India’s nuclear research facilities at Trombay, near Mumbai, and detailed interviews with a magical circle of leading Indian nuclear scientists.

All were physicists fiercely loyal to the memory of Homi Bhabha, who had died in a mysterious air crash on the outskirts of Geneva in 1966. Twice nominated for the Nobel Prize for Physics, Bhabha founded the Tata Institute for Fundamental Research (TIFR) after returning to the country from Cambridge during World War II.

He was helped by relatives from the fabulously rich Tata dynasty and after the building of the institute was approved, it was a short hop, step and jump for Bhabha to a lifelong friendship with independent India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, who he addressed as ‘bhai’ or brother.

After his death, Bhabha’s key lieutenants – the top nuclear physicists Raja Ramanna, PK Iyengar, MGK Menon -- all updated me about India’s hopes of becoming the world’s next nuclear power after the US, the Soviet Union, Britain, France and China.

In public, India was consistently evasive about its own nuclear ambitions, claiming that it believed in so-called dual-use facilities for nuclear research, arguing that nuclear explosives were cheaper than dynamite for large-scale building and engineering works.

Maintaining the fiction of dual-use was essential because the plutonium needed for the Indian test was extracted from a Canadian-supplied CANDU reactor on the strict understanding that it would only be used for peaceful purposes.

The clue to India’s hidden intentions lay in a treasure trove of personal papers that once belonged to Bhabha and were subsequently stored by his girlfriend Pipsy Wadia. Like him, she was a member of Mumbai’s creative and massively wealthy Parsi community. She was the faithful companion who accompanied him on long weekends to Paris, Rome and Venice. On that fateful day of January 24, 1966, she was also due to travel with him to Geneva, but changed her mind at the last minute.

Ramanna, Menon and Iyengar, all knew about these documents and urged me to contact Pipsy to ask if I could make notes of what they contained. Pipsy readily agreed. She first invited me to drinks and tea, then to a series of lunches. It was during one such lunch that she pulled out the steel trunk that belonged to Bhabha.

The documents I personally itemised included highly confidential letters to government ministers, including the Prime Minister, as well as Bhabha’s private sketches and notes about his hopes for India to emerge as one of the world’s leading nuclear powers. When I cross referenced those documents with leading British physicists, including Blackett, they all agreed that New Delhi was on the brink of testing.

Pipsy herself had no personal expertise on nuclear issues, but was knowledgeable about the arts, especially opera. She thrived in Bhabha’s VIP glory with all the add-on benefits that few Indians could dream of. At a time when the country was desperately poor and short of foreign exchange, he was one of the few Indians outside the cabinet who could whistle up a fistful of dollars and book himself an instant flight to any foreign destination. Officialdom never dared stand in his way.

“Homi would ring and ask, ‘Pipsy, there’s a wonderful opera this weekend in Paris, would you like to come?’ I’d say yes, and off we’d go, always first class on Air India. It was wonderful,” Pipsy remembered.

Pipsy had no formal legal link to Bhabha because the two never married. So the official custodian of his papers was his brother Jamshed, known to friends and family as Jehangir. At Pipsy’s urging, I visited Jehangir’s Mumbai office to ask his permission to continue viewing his brother’s papers. What Pipsy did not know and certainly didn’t warn me about was how Jehangir personally despised her and was insanely jealous of his dead brother.

Slightly built and effete, with a high-pitched voice, he let out a torrent of abuse when I arrived by appointment at his Mumbai office. “That prostitute”, he shouted, referring to Pipsy, “Tell her I will burn my brother’s papers rather than allowing anyone to access them.”

The following day, a gang of armed men raided Pipsy’s apartment on Malabar Hill. A tear-stained Pipsy, dressed in her nighty and dressing gown, met me at her front door, telling me how she was held by the throat by one of the gang as the others foraged through her rooms before finding the steel trunk and taking it away, despite her protests. Neither of us ever saw the documents again.

One year later, in May 1974, when India finally tested, my shell-shocked friend Thomas sat with me through the rest of the night in Oxford, whisky bottle in hand, egging me on to compose a story that was sent by post to the London Times and published as an op-ed column. Wonderful results followed for me personally.

The story so delighted the newspaper’s foreign editor, Louis Heren, that he invited me to lunch at London’s exclusive La Gavroche restaurant, where he persuaded me to apply for a job with Thomson Newspapers, who owned the Times. It was the start of a long-lasting media career that took me to all parts of the UK and the rest of the world as well.

I was still writing about nuclear weapons proliferation in 1993 -- this time focusing on Iraq -- when I won a prestigious media award. Louis Heren called to offer his personal congratulations. Jehangir Bhabha would have been enraged, but Homi Bhabha and Pipsy might well have smiled.

(Shyam Bhatia went on to write one of the earliest accounts of India’s

nuclear weapons programme, titled India’s Nuclear Bomb, published by Vikas in 1979)