By Mihir Sharma

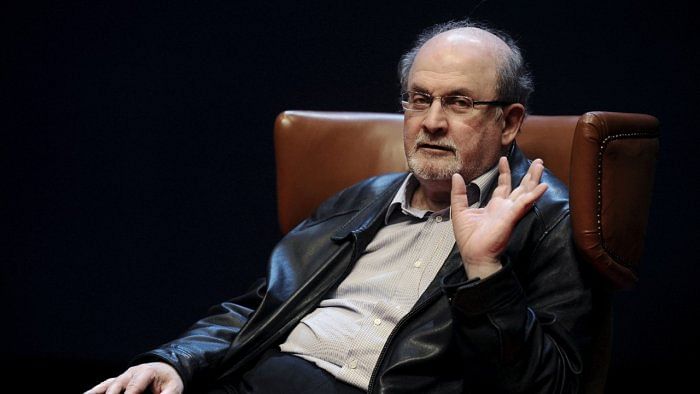

As an Indian, I claim Salman Rushdie as one of our own. He is, more than anything else, an Indian author whose writing is shaped by his heritage as a Muslim from the subcontinent, as well as a child of what was once secular, cosmopolitan Bombay (now known as Mumbai). In a piece of dreadful irony, last week’s brutal knife attack on Rushdie came just days before the 75th anniversary of the partition of India and Pakistan — the bloody event at the heart of the novel that first made his name, Midnight’s Children.

The passions, problems and politics of the subcontinent provide the correct context for the controversy over Rushdie’s most notorious book, The Satanic Verses, which appears to have motivated the attacker. Remember that while Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued the famous 1989 fatwa declaring Rushdie a blasphemer, it was the government of India, then led by the nominally secular Congress party, that first banned the novel.

They did so because the party’s approach to religious “offense” — much like that of the British viceroys whose mantle Congress inherited — prioritised domestic order above liberty. India’s criminal code contains a notorious section, numbered 295A, that criminalises “insults” to religious and other social groups. Across India, police use the statute to restrict speech daily. Just last week, a court in South India had to throw out a case registered against a big-budget Tamil film that some from the Vanniyar caste considered insulting.

Section 295A was born out of another controversy, almost a century ago, when an anonymous pamphlet about the Prophet Mohammed led to rioting across undivided India. A judge, who happened to be an Indian Christian, dismissed a case against the publisher because India at the time had no law against insulting religion. In response, the British government and Indian legislators introduced one.

The controversy drew in top political figures of the time. After the publisher was murdered by a carpenter’s son named Ilm Din, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, a supposedly secular lawyer who would go on to found Pakistan, appeared in court to argue that the young killer should be spared the death penalty. After Ilm Din was nonetheless hanged, his graveside eulogy was delivered by the poet Muhammad Iqbal, Pakistan’s founding ideologue. The assassin’s grave in a Lahore cemetery today is loaded with flowers and treated as a national shrine.

In India, Hindu nationalists see last week’s attack on Rushdie as vindication of their belief that Islam is inherently violent, requiring the state to keep Muslims on a tight leash. A national spokesperson for the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party recently lost her job and was reproved by India’s Supreme Court for remarks on national television about the Prophet. Given that she is now herself a target, on the Indian internet her case is seen as being inextricably linked to Rushdie’s.

Yet Rushdie himself has always argued that restrictions on speech hurt the powerless the most. Indeed, vulnerable members of minority religions across India are often the targets of Section 295A. A school in the northern city of Kanpur that began its school day with prayers from multiple religions, for example, was targeted by parents and police because one of those prayers was Muslim.

Across the border in Pakistan, matters are unsurprisingly even worse. Past governments, in order to shore up their Islamist credentials, added to the restrictive legal clauses they inherited. Today, the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan, a political party devoted to chasing down incidents of blasphemy, is a feared and disruptive force. Even Islamist-friendly politicians such as former Prime Minister Imran Khan are routinely accused of blasphemy. Targets who are members of religious minorities face endless harassment and are often lynched.

Meanwhile, those who kill supposed blasphemers — including Mumtaz Qadri, who murdered the chief minister of Pakistan’s Punjab province a decade ago — are hailed as holy warriors and successors of Ilm Din. In parts of the subcontinent today, Rushdie’s attacker is being similarly celebrated.

It has been more than 30 years since Satanic Verses was published, which has made it too easy to place the Rushdie attack in contexts that don’t quite fit. Some have sought to connect it to what they see as an epidemic of “cancel culture,” reflecting more than anything else their own absorption in the internecine conflicts of elite Western institutions. Others have sought to give the attack an explicitly geopolitical cast, linking it to a recent plot by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to assassinate former US National Security Advisor John Bolton.

In fact, as far as the subcontinent is concerned, the ayatollahs of the world are latecomers to the politics of blasphemy. What the Rushdie attack really illustrates is something both India and Pakistan are increasingly suffering from — the high cost of prizing religious identity over the defense of liberty.