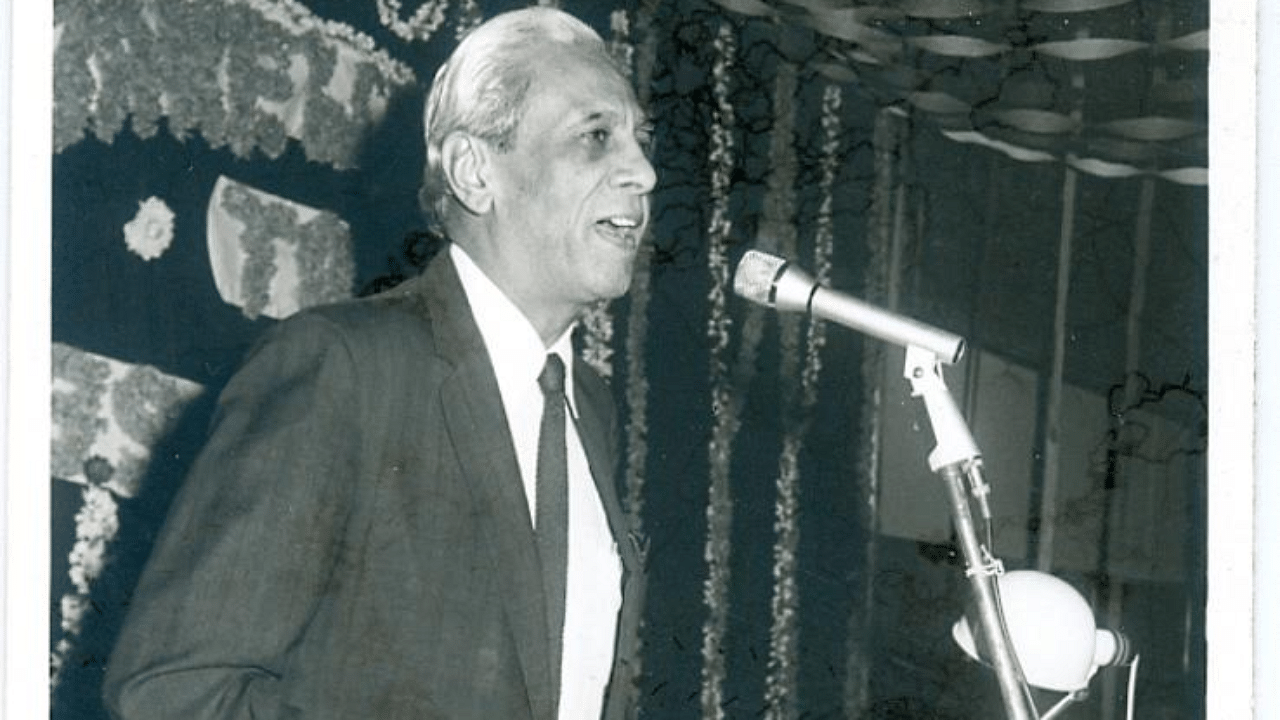

During the crucial phase of its genesis, the Indian space programme was led by people who were suited to play a role that was essential for its progress: Vikram Sarabhai nurtured it during its infancy in the early 1960s and provided a vision to it. Satish Dhawan (1920-2002), who took over the space programme in 1972, consolidated Sarabhai’s work and gave direction to the space programme. As APJ Abdul Kalam aptly put it, “Prof Dhawan transformed Sarabhai’s vision to a truly outstanding national mission.” Today, his birth centenary, is a good time to remember his contributions to the nation.

Prof Dhawan, as he was respectfully referred to by his fellow academics, students and the Indian space community, had a distinguished academic career in India and the US. Even more than that, what instilled in colleagues and students great respect and appreciation for him were his towering persona and his humanism.

When Prime Minister Indira Gandhi formally asked him to head the space programme following the sudden death of Sarabhai in December 1971, Dhawan is reported to have gently put forward two conditions: First, he did not wish to leave the directorship of the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru; and second, he would be able to assume his new duties only after completing his sabbatical at Caltech. Indira Gandhi agreed to both, and the rest is history.

Dhawan set out with missionary zeal to mould ISRO. He consolidated space activities at Thiruvananthapuram and Ahmedabad into ISRO Centres. This was followed by his choice of Kalam to head India’s first indigenous Satellite Launch Vehicle SLV-3 project, based on the assessment of Kalam’s capability as a ‘master coordinator,’ as one of his juniors recently put it. Dhawan also involved the country’s academia, research institutions and private and public sector industries in the space programme.

Dhawan presided over the development and realisation of India’s first satellite, Aryabhata, and its launch in April 1975. This was followed by three more experimental satellites, Bhaskara 1 & 2 and APPLE. Development of India’s own launch vehicles also saw significant progress during his time, beginning with the SLV-3, which successfully launched the Rohini RS-1 satellite into orbit around the Earth on July 18, 1980.

The first attempt to launch a satellite on the SLV-3 had failed on August 10, 1979. On that occasion, Dhawan told Kalam not to address the media, and instead took the responsibility for the failure on himself. Less than a year later, when the launch was successful, he encouraged Kalam to address the media, rather than taking the credit himself, revealing the quality of a true leader.

The design of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), which has now emerged as India’s workhorse rocket, was frozen during Dhawan’s time as chairman of ISRO. Focused studies on the more complex Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) were also initiated.

Other major contributions of Dhawan to the space programme include the creation of ISRO headquarters, the evolution of the participatory management philosophy, with the inclusion of senior civil servants to the ISRO Council and the pioneering of the Joint Consultative Machinery (JCM) for the welfare of ISRO/Department of Space employees. Dhawan took certain crucial decisions on cryogenic rocket technology, too, which were interpreted by some analysts as “missed opportunities.” But those decisions were based on pragmatic technical considerations. Having presided over the crucial experimental era of the Indian space programme that put it on a solid foundation, Dhawan relinquished office in 1984 after steering the programme for 12 meaningful years. The grateful Indian space establishment has named India’s only satellite launch centre after him.

Through his pivotal contributions, Dhawan facilitated India’s later emergence as a prominent space-faring nation.

(The writer is a Science Writer and Broadcaster)