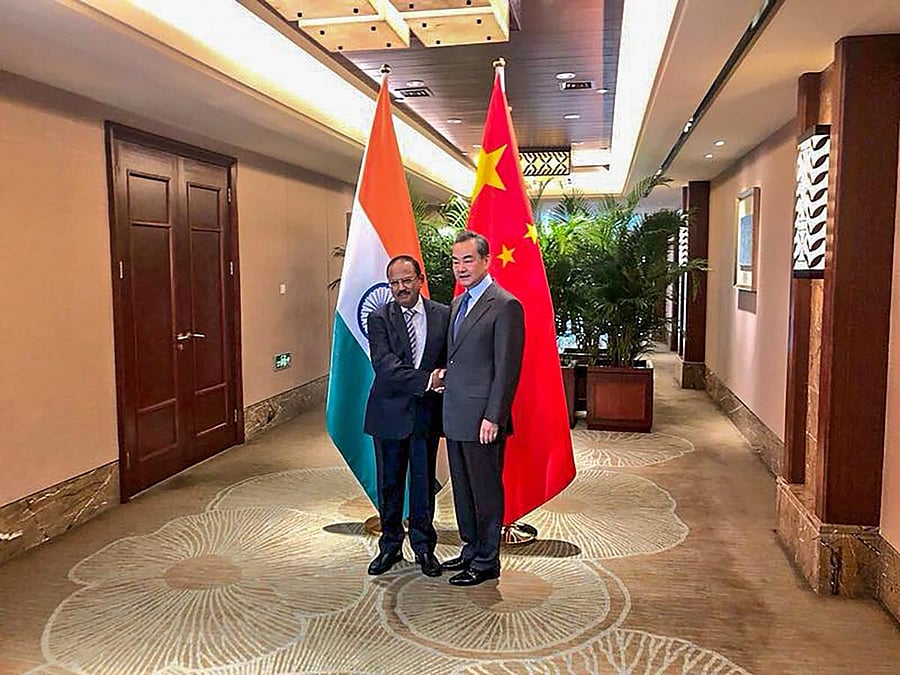

After National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and Chinese State Councillor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi spoke to each other, the two sides “agreed” it was “necessary to ensure at the earliest complete disengagement of troops along the LAC” and “de-escalation from India-China border areas for full restoration of peace and tranquillity.” The two sides have, once again, decided to “not allow differences to become disputes.”

So, even as some preliminary disengagement seems to have begun, it remains a long road to a certain degree of normalcy in Sino-Indian ties. It can safely be assumed that post-Galwan clash, India’s ties with China will never be the same again even though the two sides will try their best to sound reassuring. India would find it difficult to trust anything the Chinese side will commit to and building adequate deterrence will be its top priority. It has also signalled that it is willing to bear economic costs with its decisions to keep Chinese companies out of government contracts, infrastructure and critical strategic sectors. Its decision last week to ban Chinese apps was a symbolic move to underscore to Beijing that in the absence of a resolution to the boundary problem, economic and trade ties would not continue as before. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s message from the heights of Ladakh was equally categorical that India was preparing itself for the long haul.

China, of course, has its own set of calculations to make. While India’s assertion on multiple fronts is a new reality that Chinese policymakers must confront, it is happening in a wider global context where the world is preparing to challenge China more frontally than ever before. From the West to the East, a new consensus seems to be evolving that China’s challenge to the basic norms of the extant global order cannot go unchallenged as the costs of inaction might be too high in the future. The global landscape, which till a few months back looked remarkably benign for China, has now turned against the Middle Kingdom in a manner that Chinese policymakers can ill-afford to ignore.

While it started with the Communist Party of China’s mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic, it has now morphed into a worldwide concern about Beijing’s growing reluctance to abide by even the basic norms of global conduct. As China has been tearing up one international treaty after another, it has been making clear its contempt for those who find in these norms a certain sanctity essential to preserve global peace and stability. But China’s revisionism is too stark to be managed by the liberal idealism of norms, values and institutions.

The institutional collapse was reflected in the way the World Health Organisation was manipulated by China during the initial phase of the Covid-19 crisis. The growing divide between China and the rest of the world was reflected in the inability of institutions like the UN Security Council and the G-20 to come up with a coherent response to one of the most significant human security issues of our times. Even as the world was trying to come to grips with Covid-19, China found in the crisis an opportunity to enhance its geopolitical interests by targeting countries it thought were too vulnerable to respond. From the maritime frontiers of the South China Sea to the Himalayan frontiers, from the internal vicissitudes of the European Union to the legal framework of Hong Kong, everything has been fair game for the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) desire to strengthen its hold on a domestic population that was weathering a downturn in economy and a mismanaged health crisis.

But global political realities changed dramatically for China in a matter of months. Today, the pushback against Chinese aggression is at its sharpest. The Scott Morrison government in Australia has unveiled a new, more aggressive defence strategy which squarely targets the threat from China, warning that “coercion, competition and grey-zone activities directly or indirectly targeting Australian interests are occurring now.”

Even as China has been intruding into Japan's territorial waters more frequently in recent days, Japanese Maritime Self-Defence Force training ships conducted exercises with Indian naval vessels in the Indian Ocean and Japanese Defence Minister Taro Kono made it clear that China was “trying to change the status quo at the India border, in Hong Kong and in the East China Sea, South China sea.”

And last month, the ASEAN, too, underlined for China the limits of Beijing’s assertiveness by reaffirming much more robustly than in the past “that the 1982 UNCLOS [United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea] is the basis for determining maritime entitlements, sovereign rights, jurisdiction and legitimate interests over maritime zones, and the 1982 UNCLOS sets out the legal framework within which all activities in the oceans and seas must be carried out.”

The US, of course, has continued to pile up pressure on China both with diplomatic engagements as well as with an unprecedented show of force. For the first time since 2014, two US aircraft carrier groups are in the South China Sea soon after the People Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) concluded its five days of drills around the contested Paracel Islands.

All this doesn’t imply that the CCP would relent just as a limited de-escalation exercise doesn’t mean that China would be giving up its enhanced claims along the LAC anytime soon. But the pressure on CCP is increasing and the message to China is clear: nations will stand up to coercion and challenge China’s thirst for power. If China’s rise has a logic of its own in exerting pressure on the international system, the pushback against this rise is also a natural culmination of some of the most fundamental laws of international relations. The world must certainly brace for China’s rise, but China should also brace itself for a world that will not easily acquiesce to Beijing’s revisionism.

(The writer is Director, Studies, at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi and Professor of International Relations, King’s College, London)