Credit: DH Illustration

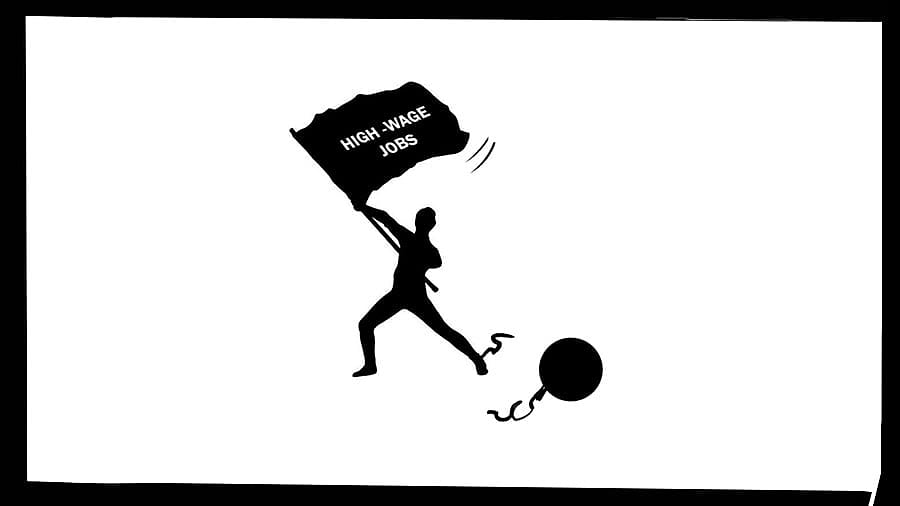

Nobel Prize economist Daniel Kahneman observed that we instinctively step on the accelerator when wanting to go faster, but we often get better results by releasing the brake. Karnataka’s current lead over other states in high-wage job creation has historical human capital roots from the visions of C V Raman, Visvesvaraya, Jamsetji Tata, Mirza Ismail, Madhav Rao, and chief ministers who expanded engineering education. The state could greatly widen this lead by making ourselves even more fertile soil for high-wage job creation through a national first innovation: a 12-month mission mode review mandates decriminalising 1,175 provisions in state legislation and employer rules.

Public policy has a bird’s eye view, but accelerating high-wage job creation requires a worm’s eye view of the daily life of job creators. A report, Jailed for Doing Business, by Gautam Chikermane at the ORF and Rishi Agrawal at Teamlease Regetch, painstakingly documents the jail provisions across 1,536 laws in seven categories: labour, secretarial, environment, health and safety, finance and taxation, industry-specific, commercial, and general. These 843 laws have 26,134 criminal provisions; 55 per cent of provisions prescribe more than one year of jail, 38 per cent of laws have five jail provisions, and one law — The Factories Act of 1948 — identifies 700-plus ways to end up in jail.

Karnataka’s job creators must cope with the 5,239 criminal provisions in central laws besides the 1,175 criminal provisions (52 per cent of total compliances have jail provisions) from state laws. Of the 2,195 compliances businesses must follow, 54 per cent carry imprisonment clauses. About 67 pr cent of these clauses prescribe sentences of up to three years, while 39 per cent impose sentences ranging from three months to a year or more.

The Factories Act, 1948, in conjunction with the Karnataka Factories Rules 1969 has 706 imprisonment clauses and the inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act 1979, read with Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Karnataka Rules, 1981, comprise 127 imprisonment clauses.

Counterintuitively, excessive regulatory cholesterol hurts small employers for whom it is a dagger in the heart more than big employers for whom it is a thorn in the flesh. This excessive compliance burden represents what economist Shamika Ravi imaginatively describes as tyranny without a tyrant. The Vishnu Sahasranamam presciently anticipated the corruption challenge: Saha-srarchi sapta-jihvah saptai-dha sapta-vahanah, Amoorti ranagho chintyo bhaya-krudbhaya-nashanah (amateur translation: fear is created so it can be taken away). Excessive and arbitrary power breeds corruption via transmission losses between how the law is written, interpreted, practised, and enforced.

Karnataka has a high-wage economic landscape with 47 per cent of non-farm workers employed in the formal sector, and 75 lakh monthly provident fund payers. Our 5,500+ IT/ITES companies and 750 companies contribute to over $58bn of exports. The IT industry contributes to over 25 per cent of Karnataka’s GDP, and we rank first among states with 41 per cent of India’s software exports of $155 billion, and 21,000+ DPIIT-recognised startups (47 per cent women-led). This demand is powered by 90 higher education institutions and 10.6mn school students.

Karnataka’s job challenge in reaching our $1 trillion GDP goal is clear; we don’t have a shortage of land, labour, or capital, but a challenge in how these combine — what economists call Total Factor Productivity, and is generally referred to as entrepreneurship or innovation. Putting Karnataka’s poverty in the museum it belongs to needs raising the productivity of our regions (too many people in Northern Karnataka work in agriculture, and it is inadequately urbanised), firms (there is a 24 times difference in productivity between our largest and smallest manufacturing firms), and individuals (we have a four-times difference in salary for same age kids with the same paper qualification).

An effective employer rule of law regime tackles information asymmetry, market power, and negative externalities, but encourages entrepreneurship to create high-growth formal firms that pay high wages; our current employer regime creates dwarfs (small firms that stay small) rather than babies (small firms that will grow).

The injustice argument for decriminalisation is also important. Courts have seen penalisation as a question of legislative wisdom, but common-sense standards for criminalisation, such as ‘harm to others’, have been suggested by academics like Andrew Ashworth and Joel Feinberg. Ten commandments (a few laws tightly enforced) rather than tens of thousands of commandments (most selectively enforced) will empower the powerless. Philosopher John Ruskin suggested, “Punishment is the last and least effective instrument …. for crime prevention”. Adding 300-plus jail provisions yearly for 70 years in labour laws has not protected our workers.

The timely and fair prosecution of wrongdoers will end the economically toxic narrative of Pramaanika (honest) as Avivekhi (fool) that currently encourages deals over rules. Karnataka can start changing this by appointing a commission mandated to decriminalise state laws with a new methodology called ‘Reversing the Gaze’, which calls out the areas where criminal provisions are required and mandates the removal of the rest.

The possible areas could be: a) physical harm to other individuals, b) intentional defrauding of any stakeholder (employees, lenders, shareholders, and government), c) externalities to societies so large that the violator cannot compensate, like public order, national integrity, trust in property rights, etc., d) no jail provisions in general clauses and all clauses that don’t specify the crime or define the crime too broadly, and, e) no jail provisions related to delayed and inaccurate filings, procedural infractions, incorrect calculations, and wrong formats. These provisions must be applied retrospectively to stock (existing laws) but must be adopted for flow (new legislation, rules, etc.).

The excessive criminalisation of employer compliances represents a dated ‘tug-of-war’ metaphor between job creators and the government that vilifies entrepreneurs. It must be replaced with a metaphor of a ‘dance’ between partners with different, crucial, and complementary roles. Our current employer compliance Niti creates poor economic Nyaya by encouraging corruption, breeding low wages, and sabotaging the infrastructure of opportunity. It’s time for change.

(The writer is with Teamlease Services)