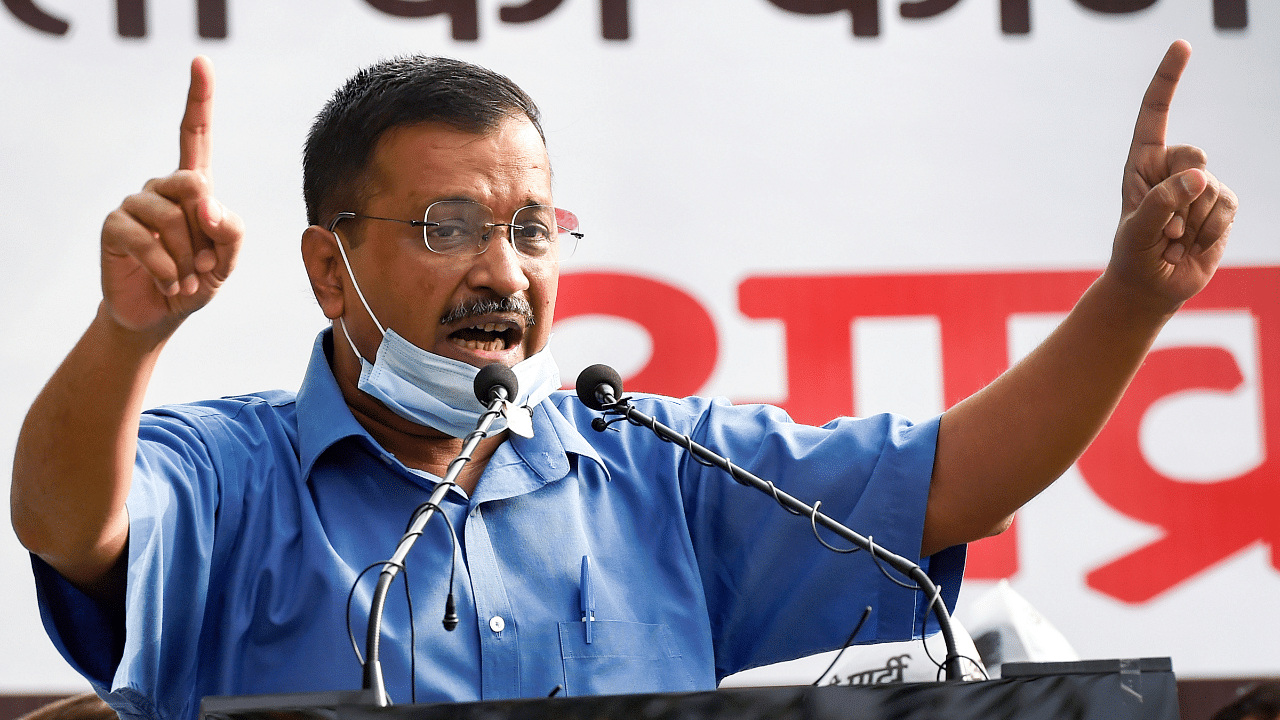

Can Arvind Kejriwal's Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) emerge as the third pole of what has essentially remained a bipolar political situation in Prime Minister Narendra Modi's home state of Gujarat? Or, will the AAP merely come up as a game spoiler for the Congress in the year-end Assembly elections?

In the previous 2017 elections, the Congress - benefiting from the statewide agitation for reservations to Patidars in government jobs - had put up a spirited show by winning 77 seats against the BJP's 99 -of the Assembly strength of 182 seats. How does that situation change this year after the entry of the AAP? The question, possibly, is best explained by comparing the contrasting approach of different political parties.

Contrasting campaign styles

Since the Punjab and Uttar Pradesh Assembly results, the PM has been on an inauguration or foundation laying functions on two visits to Gujarat already- having inaugurated projects worth Rs 23,000 crore on his last visit. Kejriwal, along with newly appointed Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Singh Mann, has also held a roadshow in Ahmedabad, and AAP volunteers have fanned out across the state's 33 districts for a ground survey of the state government's schools and hospitals.

Meanwhile, the Congress high command has seemed to be struggling over existential issues: How to keep the Congress legislature party intact amidst reports that 10 Congress MLAs are willing to switch over to the BJP. Since 2017, approximately a dozen Congress MLAs have already jumped the fence, while new poaching threats have emerged from the AAP.

Earlier this month, influential Patidar leader Indranil Rajguru and Vasram Sagathia, both former Congress MLAs, joined the AAP with others, including corporator Komlaben Bharai. The AAP has also sent feelers to the state Congress working president Hardik Patel, who has expressed public anguish at being "sidelined and humiliated" by his party. The Congress has been battling other issues, including dilemmas of whether poll strategist Prashant Kisho should get complete charge of managing the Gujarat elections. Party leaders are also divided on the possible induction of Naresh Patel, a Saurashtra based industrialist who reportedly has considerable influence amongst both the Leuva and Kadwa sections of the Patidar community. In short, while the BJP and the AAP have hit the ground running, Congress leaders remain entrapped in prolonged firefighting and an election strategy formulation exercise.

Modi's combative politics

In the 2017 campaign, Prime Minister Modi travelled on a seaplane on the Sabarmati riverfront and took a ride on a small section of the Ahmedabad Metro. The seaplane has reportedly been in repairs for more than two years, while the Ahmedabad Metro has not made substantial progress. But Modi and the BJP have moved on to other things. A few months before the Assembly elections, the PM is expected to inaugurate the high-speed rail (bullet train) station at Surat, the Ahmedabad hub, which will combine the high-speed station with the metro, BRT and two existing railway stations of the Indian Railways. The launch of other big-ticket projects is being lined up.

The Prime Minister's or the BJP's developmental pitch, powered by welfarism and the Hindutva appeal, has been a potent mix. During a recent visit, such responses were commonly heard from Surat to Bharuch and Vadodara: "Petrol prices have gone up because of global trade issues, but the BJP government has built roads, provided uninterrupted electricity and has been transferring money directly into accounts of farmers and others."

The change that Modi has brought about with his combative politics, according to Ahmedabad-based senior journalist RK Misra, is this: "The BJP does not just want to capture the ruling party space, it wants to capture the opposition space as well." A dose of the BJP's streetfighter methods was recently witnessed at Surat, where the AAP had made significant gains in the municipal corporation elections. The diamond merchant and philanthropist Mahesh Sewani was among those who joined the AAP at a much-publicised event. Within days, the majority of the newly elected councillors hopped over to the BJP and Sewani himself announced his exit from politics to concentrate in the area of social work.

Old-timers recall a previous election campaign of former chief minister Shankarsinh Vaghela against whom seven independent candidates going by the same name had been fielded - allegedly at the initiative of the BJP. It was also not just a coincidence that all ten former state ministers of the Congress had lost the elections in 2017. "Because of the way the BJP plays its game, it will take a huge effort to dislodge it from power," senior Ahmedabad based journalist Rathin Das said.

The AAP hopes

In its first Gujarat elections, where the party is contesting all 182 seats, the AAP seems to have stumbled on the correct agenda: The poor condition of government schools. In an answer provided to the state Assembly by state Education Minister Jitubhai Vaghani recently, the Gujarat Government conceded that there was just one teacher deputed to 700 primary schools, while 86 schools had been shut down and 496 merged during the current term of the BJP government.

After Delhi Deputy CM Manish Sisodia raised the matter, the Gujarat education minister came out with comparative data on the lack of infrastructure in Delhi schools. Vaghani even made a politically damaging comment by saying that those unhappy with Gujarat schools were free to take the 'transfer certificate' to move elsewhere. The AAP's best-case scenario, however, seems to be that of winning 20-30 seats - although the party's own projections are that it will win 55-58 seats.

The issue is this: Will the party eat into the traditional share of the BJP or that of Congress? Like the BJP, the AAP is an urban-centric party, while the Congress has retained its base in rural Gujarat. By such logic, the AAP will damage the BJP more. But the flip side is that Gujarat's urban workers are fed by migrant workers from rural areas. To that extent, the AAP candidates could harm Congress as well. The larger issue is this: Whether the AAP performs reasonably well or poorly will largely depend on how rapidly and effectively Congress can put its act in order.

(Srinand Jha is a journalist)