The sprawling penthouse in South Ridge, downtown Dubai, with its panoramic view of the rolling dunes wasn’t exactly Pakistan Army GHQ. Not by a long chalk. But with former soldiers in mufti clicking their heels, smartly saluting the stream of visitors who came knocking at former President Gen. Pervez Musharraf’s door in his swanky refuge in the United Arab Emirates, far from the cut and thrust of politics in Pakistan, it came close.

It is where his two worlds, the military and the civilian, would collide. Indeed, the Musharraf of April 2012 in his civilian avatar was no less headstrong or self-delusional as the Musharraf of July 2001, who had opened up to me, 48 hours before the Agra summit. All bluster and braggadocio then, swanning it in tennis gear at his plush home in Rawalpindi GHQ, he thought little of throwing the ‘Kashmir or nothing’ bomb under the Agra bus, expecting Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee and the army of doubting Thomases led by L K Advani and Jaswant Singh to overlook how he had derailed the Vajpayee-Nawaz Sharif Lahore Agreement with his Kargil misadventure.

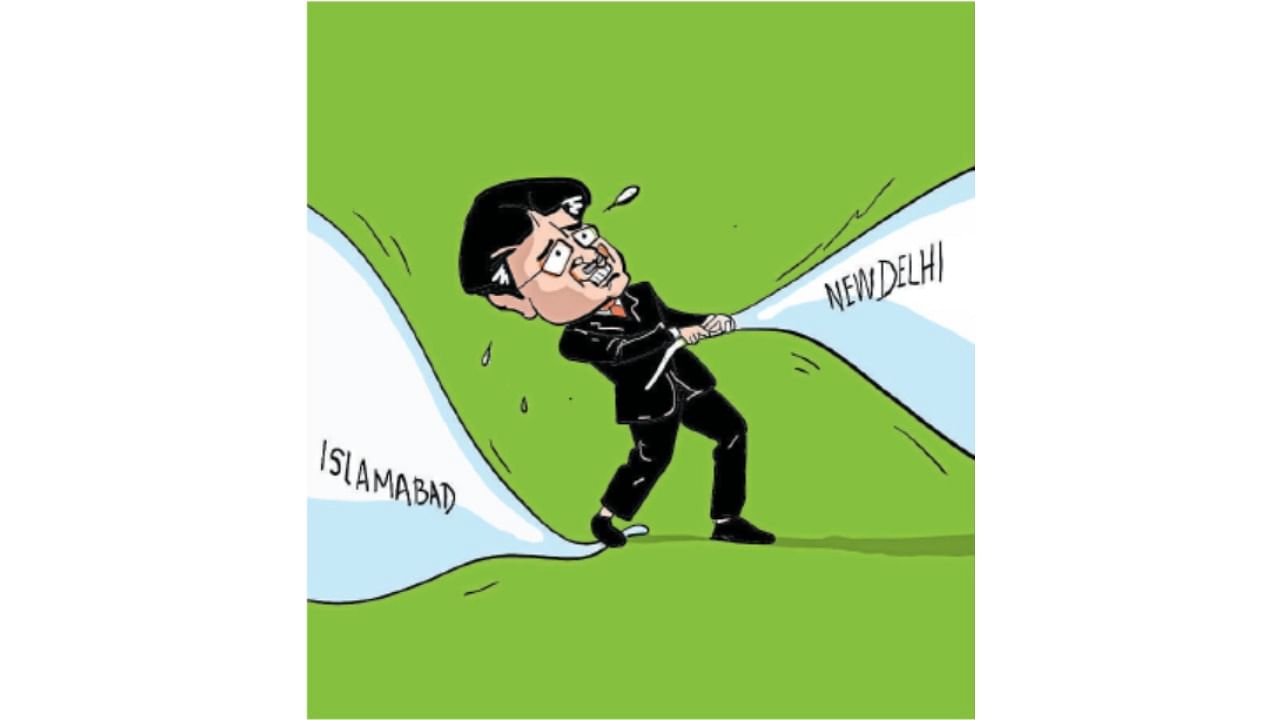

As the self-described ‘soldier-president’ succumbed to an auto-immune disease on February 5 at the American Hospital in Dubai – more than a decade after our last meeting – it’s time to acknowledge that his repeated attempts to forge a relationship with Delhi transformed the perpetrator of Kargil into an improbable and unlikely votary of India-Pakistan peace, albeit a flawed and failed one.

Even Indian leaders in Kashmir salute him for his efforts to find a solution to the Kashmir issue which began with his enthusiastic embrace of Vajpayee’s invitation to Agra.

“I am going with an extremely open mind…And I am intrigued whether the Indian leadership is going to accept the centrality of the Kashmir issue…because when they invited me, my stand was unambiguous…” he would tell me.

The talks were initiated after Vajpayee’s National Security Adviser Brajesh Mishra, along with Defence Minister George Fernandes, reached out to Musharraf’s envoy in Delhi, Ashraf Jehangir Qazi. Left unsaid was the pressure from Washington, egged on by the CIA-inspired Kashmiri lobby in the US led by Kashmiri-origin businessmen Ghulam Nabi Fai, pushing for the separatist Hurriyat leaders to be given precedence. Until, of course, Musharraf fell out with ISI-backed Syed Ali Shah Geelani, and instead chose to back the next-gen Abdullahs and Muftis. He would go further, amending his insistence at Agra that the “LoC is the problem, not the solution,” to a pragmatic “We need to open our borders to trade, to people-to-people movement,” which would become the centrepiece of his four-point formula, offered first to Vajpayee and then to the Manmohan Singh government.

He was all for the Suchetgarh-Sialkot, Drass-Batalik and Muzaffarabad-Srinagar border crossings to be opened, saying how “the people of Sialkot can see the lights across the border. And vice versa. It’s a shame. We need not one but many Wagahs,” and underlined how close he had come to a peace deal: “An agreement on Sir Creek and Siachen could have been signed yesterday.”

And he was not one to hide the fact that he had had his envoy pursue back-channel talks. “Everyone knew the back-channel was happening and after some time, I simply did not deny it. It made real progress, but I was disappointed. The promised Islamabad visit in 2007 by Manmohan Singh, where the agreement would have been signed, did not happen. Why didn’t he come? Were there domestic compulsions?”

“As for Siachen, this is a question of leadership. Why are the two governments sitting on this when both sides agreed that the best solution is to withdraw to an agreed point and let the area of contention be turned into a no-occupation zone,” he wondered. But the Indian Army had put its foot down.

In a sign that he was no longer trapped by the past, he said leaders in Delhi and Islamabad needed “sincerity of the head and heart, flexibility to learn to let bygones be bygones, to leave the last 60 years behind and move on…to a future where India and Pakistan become partners.”

In contrast, Musharraf’s legacy at home remains marred by his brutal decimation of political opponents, which made elements in the army and ISI see the Delhi-born Mohajir as an untrustworthy mass leader. He had confined the man he overthrew from office in his October 1999 coup, former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, in a room that was no more than a muddy hole in the wall at Kot Lakhpat jail. Unschooled in political statecraft, caught in the hubris of power, and unable to shed deep grudges against his opponents, Musharraf’s folly was that he failed to fathom that even as top dog, there were some red lines he should not have crossed.

At the height of his powers until 2007, he had an army of spooks to intimidate political adversaries and the media – including journalists like me. I was personally a target. He had me followed everywhere and accused me of spying for India. He even tried, but failed, to get me banned from the UAE. My crime? I interviewed his arch enemy Nawaz Sharif, and then Senator Sana Ullah Baloch months later, after the killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti set off the Baloch insurgency. That insurgency, for which Musharraf blamed India, simmers to this day. When I collared him about the attempt to banish me from the UAE at our 2012 meeting in Dubai, the man claimed he knew nothing about it – showing the personality trait that made him untrustworthy, and perhaps what made his peace-making efforts fail.

Musharraf, who survived two assassination attempts (one of them after India’s RAW tipped off the ISI, as former ISI chief Assad Durrani revealed) after his crackdown on militants in the famed Lal Masjid encounter, made a series of blunders. Not only did he inflame separatist elements in Balochistan, he took on the judiciary. It ended in him being forced out of office in August 2008 and forced to flee to the UAE.

But the biggest question mark remains over the degree of his involvement in the December 2007 assassination of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, with whom he held round after round of needlessly unpleasant argumentative negotiations through then ISI chief Ashfaq Kayani, when Benazir was living in self-exile in Dubai and had won American backing to return to Pakistan to fight elections.

Musharraf denied any hand in her death during our 2012 meeting. “It’s a bogus charge. I am not responsible for Ms Bhutto’s assassination. In your country, if a politician is shot and killed, would the blame be laid at the door of the President? I was as much responsible for Benazir’s security as the President of India is for the safety of a politician. I was President, not a security guard,” he said, bristling at the charge.

I became privy to the Musharraf-Benazir conversations when the former Prime Minister would call on her way back from Abu Dhabi, close to tears, asking me to meet her at a toy shop in a mall close to our homes. Deeply upset over Musharraf’s unwillingness to let her return home before elections, she would tell me, time and again, how he threatened her and said he could offer no guarantees for her safety if she returned. On October 18, 2007, she would insist that I travel back with her when she returned to Karachi where, at the Karsaz intersection, two suicide bombers would detonate themselves within a few hundred metres of her fortified bus. She survived that attack. But two months later, in December, after a public rally in Rawalpindi, her luck ran out.

Her son, and Pakistan’s current Foreign Minister’s Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari’s tweet on Musharraf’s passing, “Tu zinda rahygi Benazir..” is a telling comment on the former dictator’s failed legacy – that of a man who wanted to be a peace-maker but who did not know how.

(The writer is a senior journalist and former Foreign Affairs Editor of Gulf News who has reported from various hotspots in South Asia and the Middle East)