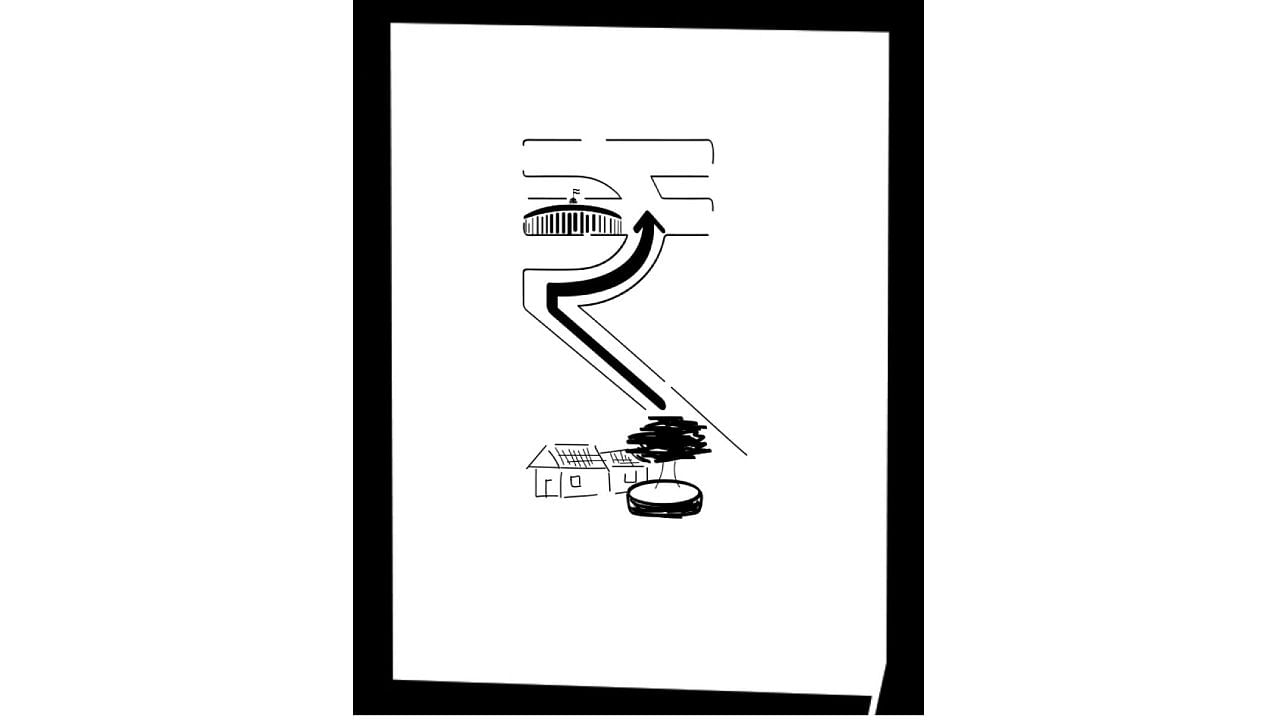

India’s economic future will be better served by promoting a bottom-up approach to economic development and changing the local institutions and technologies from below, facilitated by the central government and outside experts.

Concerns have been raised that India is now too big to be governed from the top. The benefits of a top-down approach to economic growth, for a country with the largest population in the world, have resulted in rising inequality across different population groups, and geographic areas. A bottom-up approach to policy making has long been recognized as an efficient instrument for delivering economic and social services to meet the needs and aspirations of the people. Large countries like China, India, and USA are too big to be governed efficiently from the Centre.

India’s economic future will be better served by promoting a bottom-up approach to economic development that will create a level playing field. The benefits of democracy will be fully achieved with decentralisation in political, administrative, and economic agenda. India has achieved political decentralisation with people choosing their representatives for different government levels. It has also achieved administrative decentralisation that has enabled authority to be shared with state governments. However, India has not achieved economic decentralisation. Why?

Fiscal Decentralisation

Although India is highly decentralised, more than 50% of total government expenditure at the state level goes towards interest payments and salaries, leaving less room in the sub-national government’s budget for development initiatives. Lagging states do receive higher per capita fiscal transfers than the leading states, but discretionary schemes show higher per capita expenditures going to the richer states. Food subsidies that are spent on food procurement through above-market procurement prices, go to the richer states. If we look at the second-biggest source of subsidies, fertiliser, we see that this benefits richer regions much more than poorer regions. There is a great deal of room for improving economic democracy through fiscal decentralisation.

Administrative Decentralisation

As with fiscal decentralisation, India is more decentralised than the world average, but the extent of administrative decentralisation varies across different services, and considerable variation in the degree of variation in the decentralisation of execution and supervision. India has focused more on scaling up services that are centralised, like physical infrastructure, but faltered in delivering services related to human infrastructure, like education and health.

Unfortunately, the adverse impact of weak decentralisation can be seen in many service delivery outcomes. The advantages of better local information and monitoring have been offset by weak institutions and capacity. Empirical evidence does not support a consistent positive relationship between the degree of a heavy administrative centralisation, and investment in people’s education and health, which is the best indicator of public service delivery.

Political Decentralisation

With a population of more than 1.2 billion people, India is the world’s largest democracy, with a free political representation in a complex mass society. Assessing the link between political decentralisation and institutions and economic growth is still new to economists, and concerns have been raised that the expansion of the franchise, with weak institutions, may open doors for clientelism and various forms of corruption.

India has experimented with changing institutions that govern democracy, and some economic lessons can be drawn from them. It has a three-tier system of elected local governments at district, block, and village levels. In 1992, India approved 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act that encompassed a set of reforms implementing a nationally standardised and decentralised system of local government. These reforms, also known as the Panchayat Raj, not only accelerated decentralisation but also began the process of eliminating gender inequality, by requiring one-third seat reservation for women in the local governance bodies.

These political changes scaled up women’s economic participation and boosted economic growth. The empirical evidence on the links between political decentralisation and economic growth is still evolving. However, a key message that has emerged is that the precondition for poverty reduction is increased empowerment at the grass-roots level, and working within the political systems that may not be perfect. India’s economic growth will not be fostered by running a parliamentary system in a presidential style, but by scaling up empowerment at the grass roots level, and helped by central government and technical experts.

India needs to shift from a top down to a bottom-up approach to economic development, and unbundle the decentralisation agenda to promote economic democracy—shift from scheme based transfers into broad programmes to increase rural livelihoods, and provide resources and expenditure responsibility to attract and hold the interest of the local community.

There are many challenges facing fiscal decentralisation. While the systems of interstate fiscal transfers do transfer greater resources to the lagging regions, this is mostly the case when such pro-poor redistribution has explicit rules. This is not the case with all forms of implicit interstate fiscal transfers. Some transfers from the central government to sub-national governments tend to be skewed toward richer states, the most illustrative examples being India’s discretionary schemes. Fiscal transfers would benefit from more explicit rules, greater transparency, and ensuring that interstate transfers do not act a disincentive for fiscal responsibility by sub-national governments. Simply directing financial resources to lagging regions may not be sufficient and will need to be complemented with improved capacity, accountability, and participation at the local level, so that lagging regions can make full use of these resources.

The decentralisation agenda need to be better aligned with the fast-paced urbanisation agenda. Most cities are financially broke and not able to address the challenges they face--availability of clean drinking water, public transport, transport management, treatment of wastewater and effluents, or affordable housing. States need to shed their supervisory and operational roles vis-à-vis municipal bodies. A city government should be led by an empowered and autonomous chief executive with the municipal body. City mayors need to be more tech alert.

More fiscal resources are needed to support India’s rural structural transformation. Under the present arrangement, panchayats make no contribution to the design of the schemes and are given little discretion in implementation. They also have limited autonomy over their staff. The expenditure assignments need to be spelled out in detail so that this results in local governments having autonomy and sufficient resources to provide meaningful services to their communities. Earmarked transfers designed by higher levels of government should not dominate local government finances. It is important to begin developing these capacities to improve economic democracy at the local government level to deliver local public goods.

Investment in education and skills affects the performance of students, a key driver of economic democracy. At the same time, responsibility for education, including design, financing and service delivery is assigned to different levels of government. Providing the right incentives, and aligning rules and practices in decentralisation, will improve economic and social outcomes.

(The writer has taught economics at Oxford University and worked for United Nations and World Bank)