DH ILLUSTRATION

The new coalition government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi will face numerous challenges ahead. However, the uncertainty and instability typical of coalition regimes can be reduced if an early agreement is reached on the key pillars and objectives for the coalition government.

First and foremost, the new agenda must focus on scaling up rural livelihoods to harness India’s demographic dividend. India boasts the world’s largest youth population, adding 10 million new workers annually, yet job creation remains inadequate. This trend is expected to persist for the next two decades. With India’s urban areas already congested, the potential for economic growth and job creation lies in the rural areas, where most of the people still live, and the non-farm job shortages remain substantial.

Merely expanding rural welfare programmes will not create jobs; a considerable increase in non-farm employment opportunities is imperative. One overlooked structural trend is the rise of rural manufacturing in India. Over the past two decades, manufacturing enterprises have been relocating from cities to rural areas to maintain cost-competitiveness, akin to trends observed in China and the US. This has improved the spatial allocation of manufacturing enterprises across urban and rural locations. However, India’s shift of the manufacturing sector from urban to rural areas has been slower compared to China and the US. Despite increased investments in infrastructure, which have primarily focused on cities, future infrastructure investments should concentrate more on rural areas to foster faster growth of the manufacturing sector and create more non-farm jobs.

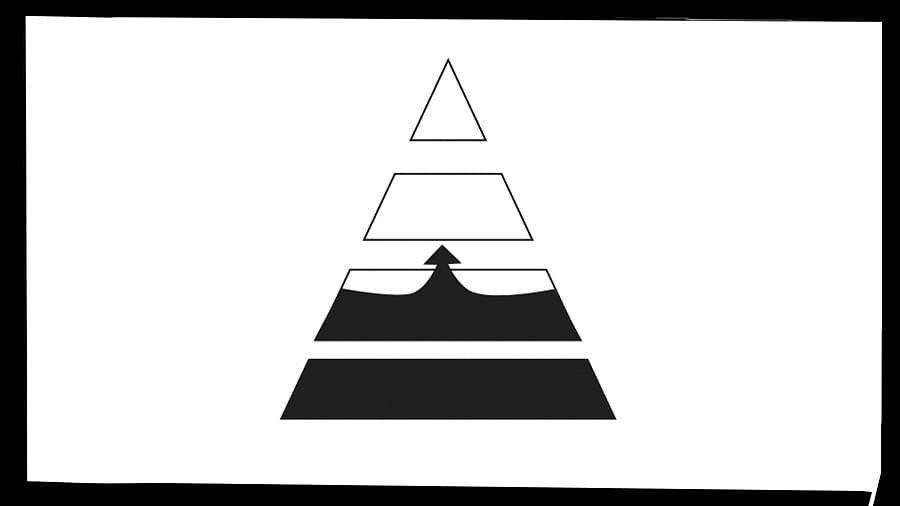

Concerns have been raised that India, given its vast size and diversity, may be too challenging to govern centrally. A top-down approach will contribute to rising inequality across different population groups and geographic areas. Conversely, a bottom-up policy-making approach is recognised as more efficient in delivering economic and social services that align with the needs and aspirations of the populace. Countries such as China, India, and the US are too big to be governed efficiently by a centralised governance structure.

A bottom-up approach will help, given that in rural areas, the local panchayats have no role in designing schemes and are given little discretion in their implementation. Most cities lack finances and are unable to address the challenges they face— lack of clean drinking water, public transport, transport management, treatment of wastewater and effluents, or affordable housing. It is important to focus on development using a bottom-up approach to improve economic democracy and deliver local public goods. India’s economic growth and rural livelihood programmes will not benefit from running a parliamentary system in a presidential style. It needs more empowerment at the grass-roots level and help from the central government and technical experts.

India needs to improve the Centre-state relationship. Emphasising “one nation and one state” has widened the spatial gap between rural and urban areas and between less developed and developed regions. Addressing India’s uneven spatial development requires enhancing fiscal decentralisation.

While states bear significant responsibility to promote economic growth and create jobs, over 50% of their expenditure is consumed by interest payments and salaries, leaving little for economic growth and livelihood initiatives. Lagging states receive higher per capita fiscal transfers than the leading states, but there is tremendous scope for improving economic democracy. Fiscal transfers would benefit from more explicit rules, greater transparency, and directing more financial resources to lagging regions for rural underdevelopment.

Administrative decentralisation is imperative not only for a more stable, efficient coalition and stable Centre-state relations but also for ensuring that states governed by opposition don’t feel threatened. The extent of administrative decentralisation varies across different ministries, with a huge degree of variation in the administrative decentralisation of execution and supervision. This has resulted in a lopsided administration that is focused more on services that are centralised, such as physical infrastructure, and has faltered in delivering services related to rural development and human infrastructure, such as education and health, that are managed at the state level.

India’s new governance agenda cannot ignore 50% of the population, and it needs to scale up the focus on reducing gender inequality. Gender inequality remains severe in India, with girls dropping out of school at a higher rate than boys, low female participation in the labour force, and even lower political representation. India has approved a new gender quota law to improve political representation of women, but its implementation has been delayed. It needs to be implemented now. Given the huge benefits from political representation of women in local elections observed over the last four decades, scaling up their representation from local to higher levels should have come much earlier.

Increased political representation of women will be the new driver of growth for India. Economic growth will come in many forms: the removal of cultural and political barriers to the participation of women in labour markets, reduced discrimination in wage differentials, and changes in management practices that will promote talented women into leadership roles. Gender equality is the new growth driver, as empowering half of the potential workforce has significant economic and social benefits beyond promoting gender equality.

Climate change impacts millions in India, leading to loss of livelihood, forced migration, and increasingly difficult living conditions across the country. India is the world’s third-largest emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2) due to its reliance on coal and oil for electricity and transportation. A lot more needs to be done to increase renewable energy and reduce coal power, and this will depend on how subnational governments are able to respond.

While there is an understandable focus on the national government’s actions, policy implementation varies a lot among the states. Several key areas of adaptation, such as water management and agriculture, fall under the purview of the state government, and a lot more needs to be done here. A bottom-up approach to climate change will help India.

(The writer is Senior Fellow, Pune International Development Centre)