DH ILLUSTRATION: DEEPAK HARICHANDAN

The journey of writing a book on the final rites and death rituals began with my experience as the chief mourner during my father’s last rites.

As a performer, I faced crucial, life-changing questions while carrying out his antim sanskar. Looking at the death worker, I wondered why Shambhu was constantly intoxicated. Similarly, I remember asking a pandit who was assisting us during my father’s last rites, “Aap kya doosre sanskar bhi karte hain?” (Do you perform other life-cycle rituals?).

He replied, “Nahin. Hum sirf mrityu se jude kaam karte hain.” (No, we perform rites related to death.) It was intriguing.

My conversations with the Tirath Purohit, the pilgrimage priest, and a keeper of the genealogical records in Haridwar were fascinating.

After a few months, a devastating pandemic struck us. A lot was going on. I read accounts of how humans dealt with the massive death toll during the pandemic. There were horrific scenes of neglect. Around this time, death work became more prominent, and everything surrounding death grasped the human imagination. I felt compelled to document the death work and mechanisms available to deal with grief during the global crisis. These experiences led me to research and write a book on the last rites and rituals of five faiths in India.

In India, funerary practices are diverse. For example, religious communities like Muslims and Christians bury the dead, while India’s Parsis expose their dead on the Towers of Silence. Similarly, Hindus and Sikhs cremate the dead.

The idea was to not just describe practices of the last rites and traditions among Hindus, Parsis, Muslims, Christians, and Sikhs on the Indian subcontinent but delve deeper into the meanings and interpretations behind end-of-life rituals with the information I gathered by speaking to ritual specialists, filmmakers, researchers, and death workers.

In the book, I describe the preparatory and post-cremation/burial rituals for the five faiths. Here, I will summarise the last rites and rituals of five faiths in India. However, there may be cultural and regional variations in the last rites I present here.

Antim Sanskar among Hindus

With a few exceptions, open-pyre cremation, or agni sanskar, has been the most common method used by Hindus since ancient times. Children under the age of two, for example, are buried. Other than this, immersing or burying sadhus in samadhi is an exception.

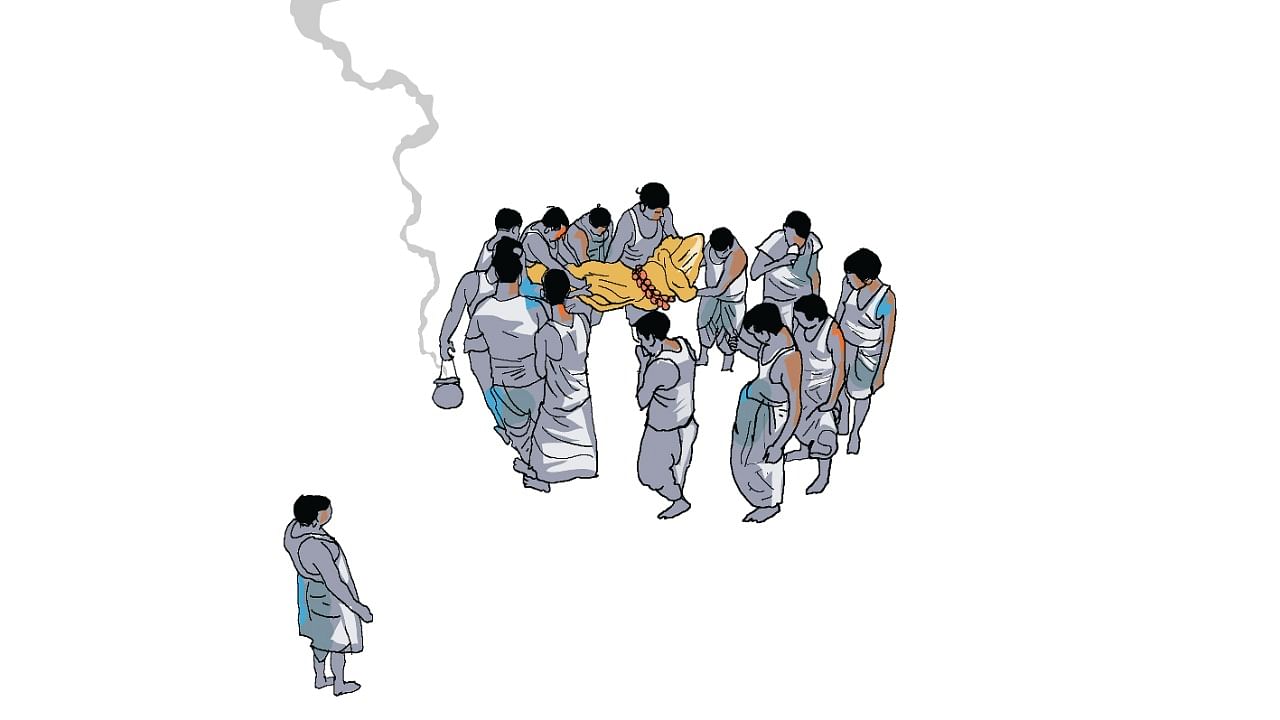

After the preparatory rites, like a ritual bath and shrouding and decorating the body with flowers, families ritually carry the body to the crematorium. Through cremation, it is believed that the body is disseminated back into the five cosmic elements from which it originated.

These days, CNG crematoriums and electric incinerators are available. However, open-pyre cremation using wood is often preferred among the Hindus. Jonathan Parry’s detailed study argues that, according to Hindu ancient scriptures, the traditional rite of cremation on open-air pyres not merely transforms the human body but further helps in freeing the spirit.

Before offering the body to the Agni (fire), the relatives conduct the final viewing of the deceased (antim darshan) while reciting a brief prayer. The accompanying members throw the dashang (a ten-substance aromatic compound) into the fire. Following this, the chief mourner circles the pyre counter-clockwise. Midway through the cremation, the chief mourner performs kapal-kriya, the skull rite, which involves breaking up the partly burned corpse and stroking the fire to ensure that it is consumed. After cremation, there are elaborate rituals like the collection and immersion of ashes, pind-daan, and offering a feast to a Brahmin, which are detailed and analysed in the book.

Antam Sanskar in Sikh Tradition

In Sikh tradition, death is to be rejoiced. It is an opportunity for the individual soul to unite with the supreme soul. The last rites of the Sikhs are performed by cremating the body through open-air burning or incineration in the electric crematorium. On reaching the cremation ground, after laying the pyre on a raised platform of wood logs and dried grass, the mourners place the deceased on the pyre. The congregation offers the Angetha Sajna Ardas before consigning the body to fire. According to Rehat Marayada, the son or any other relative or friend of the deceased should light the pyre.

After lighting the pyre, the accompanying members sit and listen to Kirtan. When the pyre is entirely aflame, the mourners recite Kirtan Sohila and offer Ardas. At the Gurdwara Sahib, the Granthi recites the Alahunia Ardas and Anand Sahib Ardas.

Once the pyre is fully burned, the chief mourner collects the remains—the ceremony is called phul chukna or angeetha sambhalna. Then, the family members accumulate the remains of the deceased to be immersed in any flowing water.

Last Rites in Zoroastrianism

The ancient Zoroastrian religion, also known as the Parsi faith in India, traditionally exposed bodies to birds like vultures at the Tower of Silence/dakhmas—the squat circular walled stone structures.

As per the Zoroastrian faith, contact between dead matter and other substances such as earth, water, and fire is forbidden. So, one should traditionally expose the body to the Tower of Silence/dakhmas to be consumed by birds like vultures and crows.

There are elaborate preparatory rites in the Parsi tradition. After these, the nasu-salars carry the body to the Tower of Silence. The designated pallbearers, who have exclusive access to the tower, place the body naked in the tower. After the scavenging birds have eaten the flesh, the nasu-salars systematically dispose of the dried bones.

However, with the extinction of the vultures, the traditional funerary practice of dokhmenishi, or sky burial, has become challenging. Efforts are being made to revive the vulture population in India. In the interim, the Parsi community is relying on artificial methods like solar concentrators in Mumbai and Hyderabad to dehydrate the body faster. However, newspaper reports suggest these means are not proving very effective.

Some members have also adopted cremation or burial as a funerary method. The ones opting for cremation use the Worli electric crematorium and adjoining Prayer Hall for funerary services, assisted by a designated priest.

Islamic Last Rites and Rituals

In the Islamic faith, there are elaborate gender-specific washing and shrouding rituals. After the purificatory rites, the family members carry the body to the gravesite. Following their arrival at the gravesite, the mourners offer a prayer for the dead, led by an imam or a devout male. The body is placed in front of the imam, facing Mecca (qiblah). Males at the gravesite stand in two to three rows behind the imam.

The grave is dug opposite the qiblah, and the body should be laid on its right side, facing the qiblah, with the head supported by a mud brick. Those lowering the body into the grave should recite Bismillah Walla Millati Rasulilllah (in the name of Allah and the faith of the Messenger of Allah). Those who lower the body into the grave cover it with a layer of wood and stones to avoid direct contact between the body and the soil. Prayer is offered by the gravesite toward Mecca. Before departing, the accompanying members recite a concluding prayer. The Muslim religion traditionally forbids the erection of a large monument, or pukhta kabr (cemented structure), on the grave.

Funerary customs among Christians

Burial is the most common funerary method followed by Christians in India. In exceptional cases, the families may have to perform cremation services in place

of burials.

Among Christians, the gravesite is prepared by digging the grave to the desired depth and size. A final prayer service is held after the members gather at the cemetery. The coffin may be kept open for final viewing until this point.

Before the coffin is lowered into a grave, family members and friends say their last farewells. These can include prayers, words of remembrance, or personal gestures of farewell, such as placing flowers on the coffin. After sealing, the family members, friends, or funeral directors lower the coffin gently into the grave. A lowering mechanism, such as straps

or ropes, is used to lower the coffin into the grave. Once the coffin has been lowered into the grave, it is precisely positioned in its ultimate resting place with the help of funeral professionals or burial staff. After placing the coffin, the grave is covered with soil. Family members, friends, or cemetery workers may take part in this process by shovelling soil into the grave, symbolising the last act of laying the deceased to rest. While placing the coffin into the grave, religious prayers or readings may be performed.

The funerary methods across religions are diverse. But I also discovered several overlaps across faiths. For instance, washing and shrouding rituals are crucial across religions. Every faith discourages excessive mourning. Not lighting the kitchen hearth during the bereavement period is another common aspect I found across all religions. Similarly, hosting a community feast is more or less a common practice.

Last rites and rituals are the last to change. However, my conversations with the ritual specialists reveal some changes are underway. For instance, in India, arranging the rites and rituals is a community affair. But, these days, the death care industry or professional funeral services have entered the scene, offering a range of services. I discuss these emerging trends in the book.

I also examine and dissect many other aspects surrounding this crucial event. For instance, gender is an overarching theme I analyse throughout the book. My curiosity about death workers led me to the ghats and kabristans of Delhi and Varanasi. I share their stories and highlight the struggles and discrimination they face. The book further explores the fascinating world of ‘death tourism’ in Varanasi. Other than this, I document the work of professional mourners hired to mourn for the dead.

The Final Farewell is an ode to life, death, and all in between. No matter what one may believe in, all forms of life share that certainty of death, so it deserves respect and care for all the stories it leaves behind for the living.

(The writer is a New Delhi-based researcher and the author of The Final Farewell: Understanding the Last Rites and Rituals of India’s Major Faiths. She has a PhD in Social Medicine and Community Health)