When does a District Collector decide that the moment has come to risk his comfortable existence? That at stake are matters far graver than his own little empire? Sardar Patel described the bureaucracy as a" "steel frame", the backbone that upholds the administration while elected governments come and go. When does an IAS officer come face to face with the thought that his next decision may weaken this frame forever?

'Sarkar mai-baap' is a concept that's still relevant, as most Indians remain powerless in the face of a massive faceless State that influences every aspect of their lives. Apart from a few metropolises, in the rest of the country, district collectors are the mai-baap, outside whose offices ordinary people wait endlessly as supplicants. In 2016, an abandoned mother of two slashed her wrists outside the Coimbatore collector's office, frustrated after seven years of bribing everyone who mattered to get a ration card for herself and her children.

Did this suicide attempt move the collector? It took a full 18 months for Oreva to get complete control of the Morbi Jhulta Pul. In August 2020, it wrote to the district collector, threatening to open the bridge with just temporary repairs. It only got what it wanted - total, unfettered control over the bridge - in March 2022. Of course, during those 18 months, the second Covid Delta wave hit the Morbi district badly; the bridge could not have been on anyone's priority list. Nevertheless, such a long gap can give rise to the question: was that threatening letter one of those life-defining moments for the Morbi collector when his responsibility to the people whose lives he controlled featured uppermost in his mind?

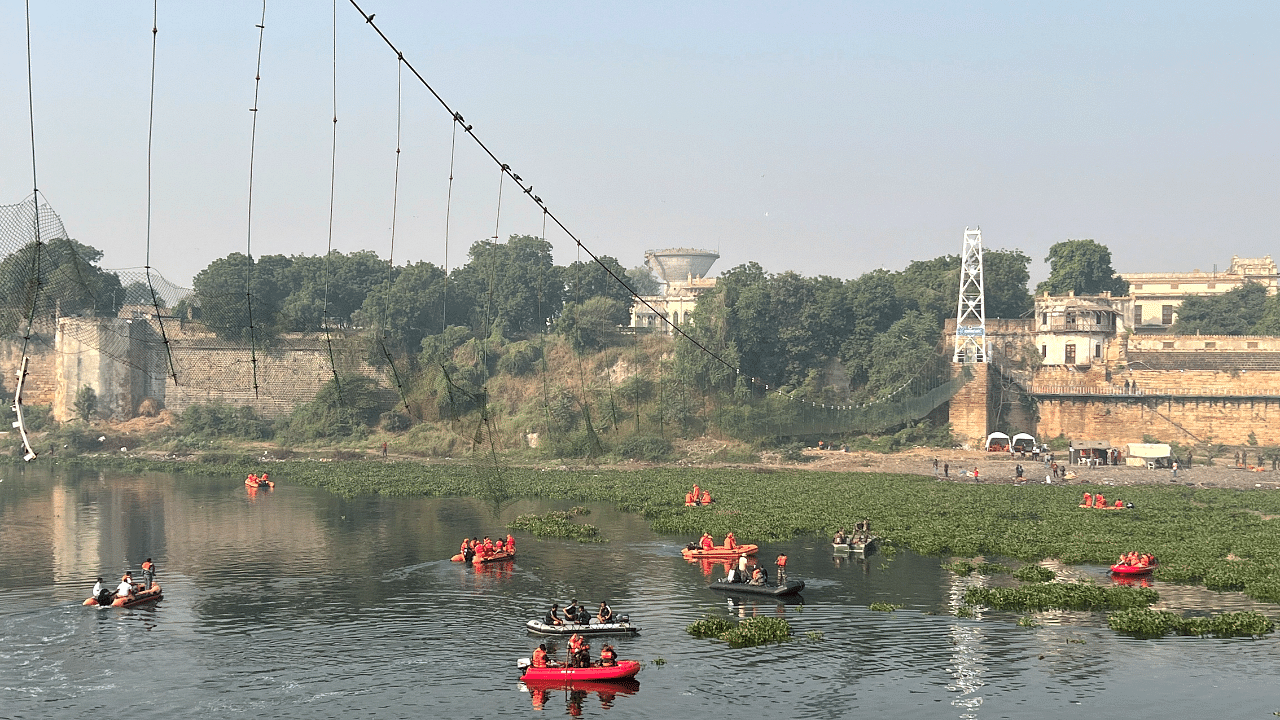

We will never know. But from the terms of the final contract signed between Oreva and the Morbi Municipality in March 2022, in which the government waived off all responsibility for its maintenance, it's obvious that even if the Collector had had doubts about handing over the town's 105-year-old heritage to a clock manufacturer, those doubts weren't allowed to get in the way of the final deal. 'Sarkar mai-baap' had willfully abandoned its flock; the steel frame of the system had been cracked, a crack that was to take 135 lives. Those who died had trusted their government; they went to their favourite bridge thinking their safety had been taken care of by administrators entrusted with the task.

When the Bhopal Gas Disaster took place in December 1984, Warren Anderson, head of Union Carbide, became the most hated man in India and remained so till he died. Yet, even at that time, it was pointed out that it was the Madhya Pradesh government that had allowed the multinational to set up its chemical plant next to a residential colony; it had ignored warnings from its own environmental board, from the municipal commissioner and the plant's union, as well as a local journalist's series of exposes on the plant. Not surprisingly, both the state and Central governments went on to protect Anderson.

Governments are known to be venal, but days after 2000 citizens living around Carbide's plant were killed instantly by the gas that leaked from it, the director of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, told the media about the necessity of "reducing, not eliminating risks", keeping the "cost-benefit ratio" in mind. No doubt, the "cost-benefit ratio" drowned all other inner voices when the contract between Oreva and the Morbi Municipality was signed for 15 years.

Incidentally, soon after the Lok Sabha elections in 2019, a high-level meeting involving the PMO was convened to discuss a scheme related to the Rann of Kutch conceived of by the owner of Oreva. Obviously, this was not your run-of-the-mill company.

Bureaucrats are known to be the first to gauge the worth of those they deal with. But they are equally adept at leaking information. The contract that is now public knowledge and before that, Oreva's letter threatening to carry out only "temporary repairs" – couldn't these have been leaked?

In his speech to the first batch of IAS probationers, Sardar Patel listed the values expected of them: impartiality, incorruptibility, integrity, working without expectation of rewards, and the spirit of service. Often, glimpses of these ideals come through when successful IAS candidates are asked by the media about what they hope to accomplish. Do all of these vanish when they finally reach a position when the decisions they take affect the lives of citizens whom they are supposed to serve? And when their decision results in irreparable damage to citizens, who should the latter turn to? Who can punish collectors and municipal commissioners for risking people's lives?

(Jyoti Punwani is a journalist)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.