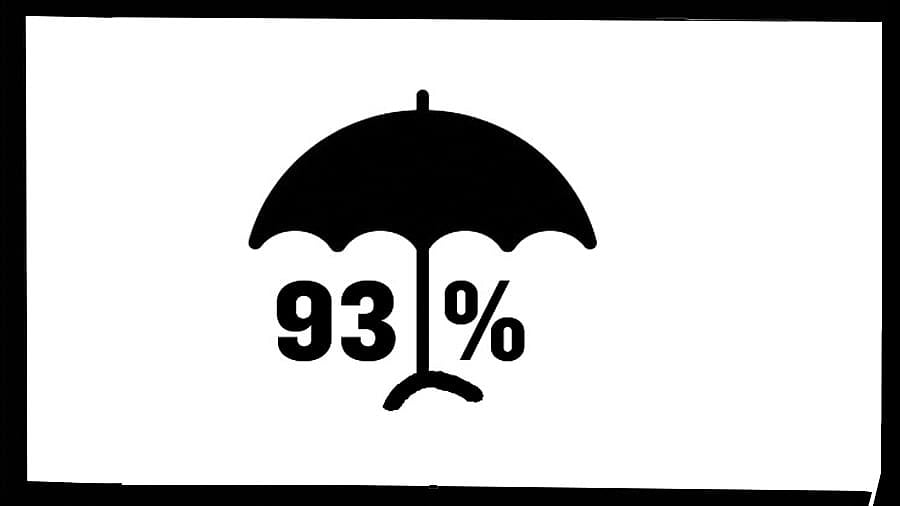

With 93 percent of all employment in the informal economy, the demand for universal social security will remain the Holy Grail for the informal sector. However, in the absence of political will and in an environment that prioritises “ease of doing business,” this demand of the informal economy may remain a distant dream. The Unorganised Workers Social Security Act of 2008, which promises universal social security, has languished for over a decade and a half.

In this context, enacting sector-specific social security schemes represents a viable interim arrangement for the progressive coverage of informal sector workers under limited welfare measures. In Karnataka, the Karnataka Motor Transport and Other Allied Workers’ Social Security and Welfare Bill, 2024, and the Karnataka Platform-Based Gig Workers (Social Security and Welfare) Bill 2024 are such attempts.

Sector-specific welfare schemes are typically cess-based, i.e., funded through a cess, and have seen considerable success in implementation, though many cess-based sectoral legislations were repealed by the 2017 Goods and Services Tax (GST) legislation.

In Karnataka, welfare measures for beedi workers were financed through a welfare cess under the Beedi Workers Welfare Fund Act, 1976. This was particularly noteworthy because it provided medical insurance coverage for many beedi workers and their families through a network of dispensaries, and access to education for children under the Act was a huge boon, offering them a pathway to escape their economic and social conditions.

The repeal of this Act now denies a safety net to some of the poorest sections of workers, primarily women workers, numbering around four lakh in Karnataka. There is a strong case for the Karnataka government to demand that the Central government reverse the repeal of these legislations and reinstate them for beedi and other similar sectors.

Since cess-based schemes are sector-specific, they are also amenable to better regulation, with well-developed tripartite mechanisms to administer these schemes. The Karnataka Beedi Welfare Fund benefited from strong trade unions that were able to defend workers’ rights, particularly concerning the quantum of cess and the administration of benefits.

The legal challenge by trade unions against large beedi manufacturers such as Mangalore Ganesh Beedi, fought up to the Supreme Court of India, resulted in important case laws on the methodology for minimum wage notification in piece-rated work. It could be argued that sector-specific social security schemes aid in strengthening union power and collective bargaining.

Furthermore, this model allows for better tailoring of schemes to sector requirements, as opposed to models that follow a one-size-fits-all method. Thus, a large cohort of workers from one sector under comprehensive health care allows for targeted study of occupational health issues and better preventive and remedial measures specific to that specific.

If we were to analyse social security schemes for the formal sector, such as the Employee Provident Fund (EPF) and Employees State Insurance (ESI), their strength partly derives from being built up from the enterprise level. Therefore, workers are aware of their rights, particularly because they are also contributors to the schemes.

The trade unions are able to ensure that employers’ pay their contributions and workers access their benefits. Social security in one sense becomes a marker to define the employer-employee relationship. Further, the model ensures that the private cost to capital for providing social security to its employees does not get socialised. The combination of EPF and ESI also ensures that all nine core components of social security for employees championed by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) are covered.

Ideally, this should be the model of social security for all workers covered by wage work, where the employer is defined, irrespective of the enterprise size. The present law restricts ESI to enterprises with 10 workers and EPF to 20 workers. If the limit is expanded to cover enterprises with five or more workers for both ESI and EPF, the number of formal sector workers with ESI and EPF coverage will increase threefold to around 10 crore. Including dependants of workers, this would lead to around a third of the country’s population getting covered under universal health care protection. Since the scheme follows the formal sector model of worker and employer contribution, this additional coverage is achieved without any fiscal burden on the exchequer.

To conclude, the expansion of social security by progressively expanding the coverage to all enterprises with five or more workers should be the first step towards universalising social security. This measure, in addition to increasing coverage of workers with access to good social security, will also contribute to trade union strength at the enterprise level and collective bargaining at the industry level.

Simultaneously, the demand for reversal of the repeal of cess-based social security would at least restore benefits to some sections of the most vulnerable informal workers. It is crucial to add here that the GST regulation resulted in converting a defined benefit tax for the poor workers in a sector to a general contribution to the central tax pool. There are surely more equitable ways for the government to shore up its resources than robbing from the entitlements meant for the poorest workers. Finally, the demand for a universal social security should remain the Holy Grail that the working class strives for in their democratic struggles.

(The writer is Visiting Fellow, Centre for Labour Studies, National Law School of India University)