“A poet’s work,” he answers. “To name the unnamable, to point at frauds, to take sides, start arguments, shape the world and stop it from going to sleep.” And if rivers of blood flow from the cuts his verses inflict, then they will nourish him.

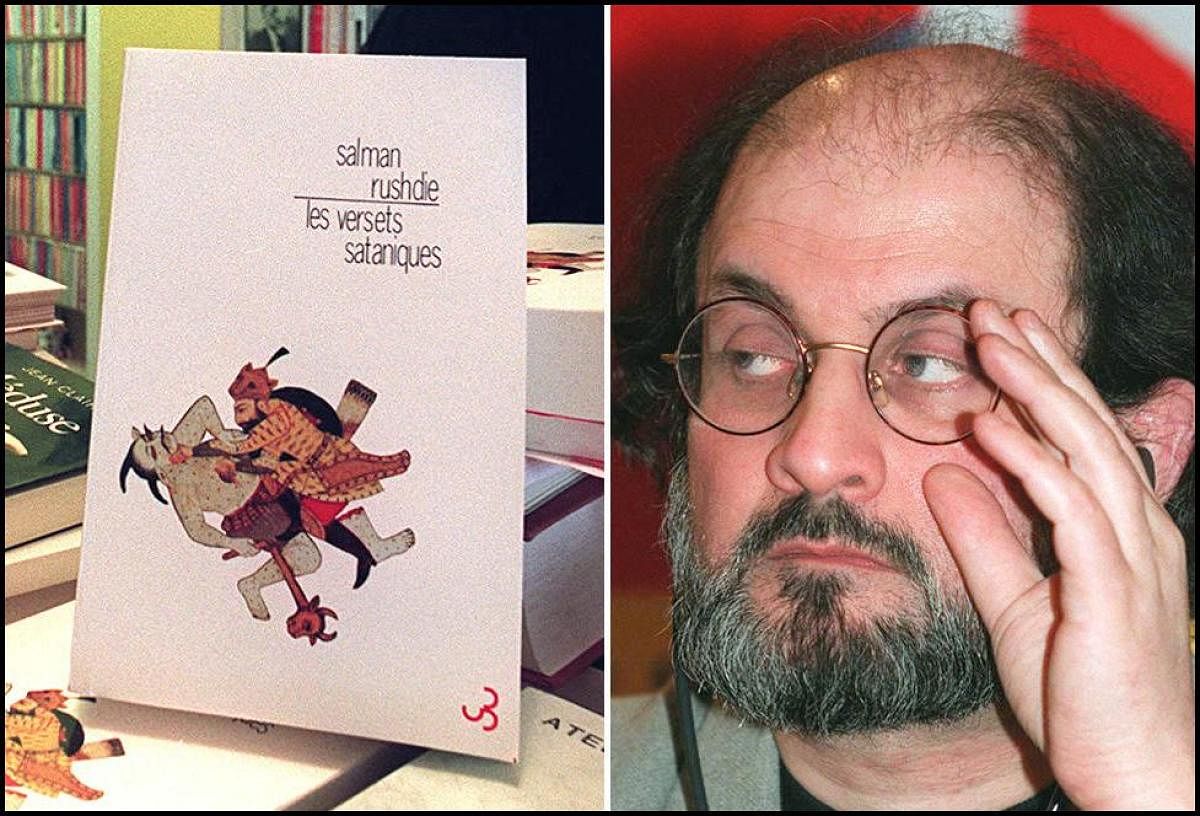

Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses.

On Independence Day, Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave a ‘clarion call’ to eliminate parivarvaad (dynastic politics) from the country. Salman Rushdie’s breakthrough 1981 novel, Midnight's Children that mounted scathing attacks on political dynasties, corruption, and the legacy of British colonialism, tempering it with abundant humour and self-deprecating jokes, gave serious offence to the ruling dispensation at that time. Foreshadowing the political turmoil that would embroil his later career (the 1989 fatwa of Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini condemning him to death for his The Satanic Verses), Prime Minister Indira Gandhi sued Rushdie and his publisher for libel, forcing them to make a public apology. The work aroused a great deal of controversy in India because of its unflattering portrayal of Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay.

Midnight's Children took its title from Nehru's speech delivered at the stroke of midnight, 14-15 August 1947. But the novel is a family story first and a political allegory about India second: a glorious reinvention of the Bombay of Rushdie’s childhood, of his own family stories. Saleem Sinai's life parallels the changing fortunes of the country after independence and the picture that comes out is not very flattering of India. Rushdie's novel ponders over the history of India (and Pakistan, and Bangladesh) through several decades, introduces well over a hundred characters, and keeps those dazzling stories magnificently entwined.

Rightfully, that novel, acclaimed as a major milestone in postcolonial literature, not only risked offending some readers, but also fiercely challenged our understanding of history, nationhood, and narrative.

The vision of India that emerges from it is more a product of the novelist's imagination than of the historian's search for truth, so much that it blurs the distinctions we often make between personal and public history, between private spirituality and communal religion. In telling both his own story and that of modern India, the narrator Saleem Sinai is confined by nothing but “the limits of his means”. He may be caught in the abstractions and vagaries of language, but the struggle is itself an expression of freedom and a vindication of the capacity of the writer's voice to shape reality. Can a writer, a poet or an artist be robbed of that right?

Had Rushdie written a similar novel on the political situation under Narendra Modi with uncharitable insinuations at the style of governance, demonetisation, lockdown, the culture of platitudes and puffery, what fate would have befallen him? Saleem's use and abuse of scriptural authority, by turns playful, blasphemous, and reverential, points to his (and Rushdie's) desire to unsettle some of the easy dichotomies that entities such individuals as well as entire cultures employ to make sense of themselves. But it's not just religion that gets such treatment – Rushdie turns his paradoxical gaze on the idea of the nation as well. How would such a treatment, if Rushdie had cared to train his gun on a 75-year-old independent India taking potshots at its majoritarian excesses, its deviation from secular principles, its growing vigilantism, a subservient media and a culture antagonistic to dissent, have been received in Modi’s India? Would he have attracted vicious hatred? Or even met the fate of Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, M M Kalburgi, and Gauri Lankesh?

When it comes to a writer speaking truth to power, he or she needs greater protection to keep on telling the truth. The trouble begins when the State capitulates to ‘mob sentiment’. Religion is the holiest of all cows. If the guiding emotion of any writer is fear before he or she chooses to write something, lest the truth purported to be expressed in his or her work come to hurt the political or religious sentiment of some people, or that he or she might get no State protection if they are threatened, then there will be no creative work. It will be as tame and bland as just boiled pasta. Yes, offence might take vicious forms. It can be tendentious, malicious and vile. It can be symbolic and literary. But the point of offence may well be stark and true. And when one takes to task mighty popular leaders, this is certain not to please their adherents. Therefore, the ‘I’ in the expression “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” should compulsorily refer to the State.

It is in this context that we should see the vicious attack on Salman Rushdie. It is an attack on the freedom of speech, assuming that 24-year-old Hadi Matar didn’t attack 75-year-old Rushdie on being defrauded or cuckolded by him, or by being just irked over his ‘inflammable’ writings but by inheriting a civilisational hatred for a writer he had barely read or understood.

Second, if it was an attack on the freedom of speech, no one can make a case for a lethal attack with the intent to kill. Then we have to accept that freedom of speech cannot come with strings attached and must come to include the right to offend. And in that case, the State and the Constitution must defend, with all their might, the unconditional freedom of speech of a writer and protect him or her, irrespective of the impact of his/her deemed offence. Even if we were to deny a writer unqualified freedom of speech, his/her acts of ‘transgression’ must be protected from rabid death threats.

To fight against fanaticism and totalitarianism at a time when the traditional opponents of freedom of speech are thriving, it is important that the nations propounding liberal democratic traditions, a scientific worldview and a secular, rationalist culture come forward to defend those values. But do they exist in the real world? Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa offering a reward to anyone who killed Rushdie, and Britain’s sturdy defence of him for years offer opposing models of the role a State can play when it comes to free speech.

Our PM has maintained a stoic silence over the attack on Rushdie, even though the BJP was critical of Rajiv Gandhi’s decision to ban The Satanic Verses in 1988. India’s diplomatic tightrope walking forbids it to be critical of Russia over Ukraine, of China over Taiwan, and now over the attack on Rushdie and, in short, anything that has international ramifications. Its failure to take a moral stand even when it is due is abject and tragic. That it cannot neither officially align with international outrage nor condemn Islamist hardliners in Iran and Pakistan cheering the attack makes its stand ambivalent and dangerous. Seventy-five years since Independence, the hope that India will once again uphold its civilisational values remains wishful thinking.

(The writer is a Kolkata-based commentator on geopolitical affairs, development and cultural issues)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH