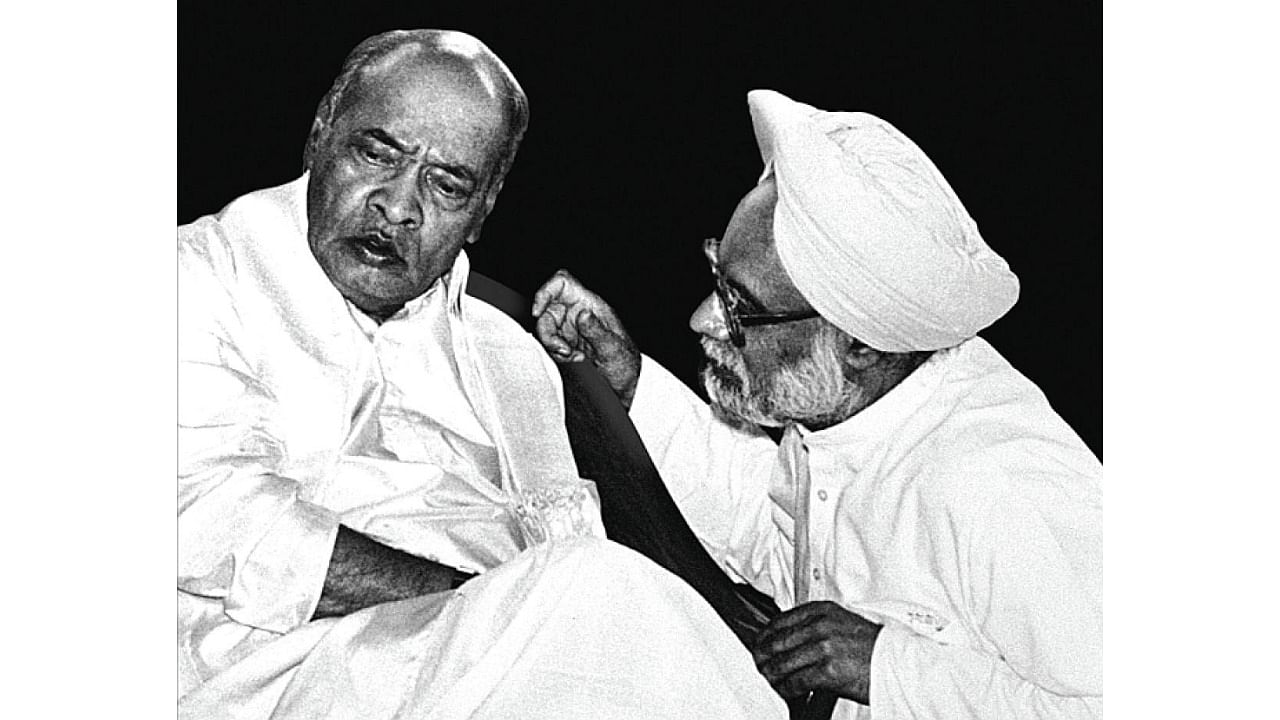

Launching the Congress manifesto in 1991, former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi promised to significantly liberalise the economy within 365 days. After his tragic assassination, the task of fulfilling this promise fell to then Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao and his Finance Minister Manmohan Singh.

They displayed exemplary courage and confronted the multiple challenges facing the Indian economy head-on. The Gulf War had triggered a spike in oil prices, expatriates were withdrawing foreign currency deposits, and the previous government had been forced to mortgage gold to meet its financial obligations. Foreign exchange reserves were enough only for a few weeks of imports.

Rao’s minority government had two options before it: resolve the immediate crisis and continue in office or risk political power by undertaking long-term structural economic reforms. Reforms were unpopular and opposed by most political parties. Yet, on July 24, 1991, presenting his maiden budget, Singh boldly embraced the “idea whose time has come” and announced the reforms that set India on the path of high economic growth.

The parallelly announced Industrial Policy ended the ‘licence-quota-permit raj’ system. The budget laid emphasis on controlling inflation, which was in double-digits, and improving the fiscal situation. Industrial licences were abolished, except for a few strategic sectors. A revised import-export policy opened Indian industries up to competition from abroad. Direct foreign investment up to 51% was allowed in specific industries. A transparent mechanism to review tariffs, which were eventually reduced drastically, further opened up the economy.

Reforms unleashed the entrepreneurial spirits of Indians and industry. India’s share in the world economy has more than doubled since 1991. GDP has grown 10 times since pre-reform levels. Average per capita income has increased from Rs 14,300 to Rs 86,700. India’s current foreign exchange reserves at $600 billion are enough to cover 18 months’ imports.

India’s middle class has grown exponentially, and a scarcity economy has given way to one where consumers are spoilt for choice. Indian industry is competitive in many high-tech sectors, and consumers have access to the best quality products worldwide. World-class infrastructure has come up across the country. Air travel is significantly cheaper. Metro rail systems have been established in major cities. With a mobile subscriber base of 1.2 billion, India’s telecom sector is the envy of the world. The information technology revolution has contributed to increased exports and strengthened our soft power.

Despite some recent setbacks, there has been a marked change in people's standard of living and the quality of jobs available in the country.

While the reforms called for realignment of national policies, Singh also stressed on his government’s commitment to “adjustment with a human face” to ensure that the poorer sections were not disproportionately impacted.

The wealth created due to liberalisation allowed for an expanded social safety net. Well-designed rights-based schemes like MGNREGS helped create an empowering welfare state. Higher MSPs for crops boosted rural incomes and helped India stave off the 2008 global financial crisis. Between 2005 and 2016, 27 crore people were lifted out of poverty.

The reforms have stood the test of time and proven their usefulness. Remarkably, successive governments with divergent ideologies have built upon the foundations laid in 1991. Yet, much remains to be done.

The role of the government needs reimagining. A troublesome spike in wealth inequality and the damage caused by the pandemic highlight the need for serious governance reforms. In 1991, the situation called for the government to exit certain sectors and deregulate. 2021 calls for the government to commit itself to ensuring universal access to essential services like healthcare and education. Social welfare cannot be delegated to market forces.

The government must also continue its emphasis on infrastructure and financial inclusion. Robust regulatory framework institutions must ensure that markets work without our people getting ripped off. The enormous NPA (bad loans) overhang demonstrates how some people get to privatise profits and socialise losses.

Thirty years after liberalisation, India finds itself in a tough spot. Unemployment has soared, food consumption has fallen, raising fears of rising poverty and malnutrition, and economic inequality has risen sharply. Demonetisation and the poorly designed Goods and Services Tax regime have derailed India's growth. Mishandling of the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated our problems. India's strong middle class, a creation of the 1991 reforms, has shrunk. Poverty and indebtedness have risen rapidly. Outstanding loans against gold jewellery have nearly doubled since last year.

The ‘humane face’ Singh spoke of in 1991 has lately been missing from policymaking. The current government has not announced sufficient stimulus measures. Interventions have focused on the supply side, offering more loans to already stressed businesses and have had little impact: GDP has shrunk by 7.3%.

India can overcome its immediate challenges only with a demand-driven approach. The solution is a direct income transfer scheme like NYAY – nyuntam aay yojana. Income support for the most vulnerable is more than a humane gesture. It will kickstart consumption and have a positive multiplier effect on the economy.

Income support needs to be accompanied by a well-targeted fiscal stimulus. Saving small businesses that have had to face the worst of the crisis must be the priority. The government must resist temptations to close the Indian economy off from the world. Raising tariffs on goods is a regressive step. Atmanirbhar Bharat should not result in isolationism.

In 1991, the nation had to mortgage its gold. In 2021, Indian households are facing the same fate. Today’s crisis, which predates the pandemic, is different in form but no less potent in its capacity to inflict damage on our people. Our economy has lost some sheen, but our underlying strengths can help us recover swiftly.

Liberalisation made India a global leader of the 21st century, enhanced our self-confidence, strengthened our professionalism and appetite for entrepreneurship. Brainpower is now our brand, thanks to our successes in the knowledge economy. India’s development story is renowned for growth with a human face. All these are the result of the courageous leadership that was displayed in 1991. It is up to us to consolidate the gains of the past and ensure an even better future for aspirational India.

(Prof M V Rajeev Gowda is a former MP and Chairman, Research Department, Indian National Congress; Akash Satyawali is its National Coordinator)